Join Me For Unabashed Gushing Over Assassin’s Creed: Liberation‘s Female Protagonist

Review

As a whole, Assassin’s Creed Liberation HD is not a very good game. The PC port of this former PS Vita exclusive looks gorgeous, but that doesn’t hide the problems underneath. The maps are huge, without providing any real reason to explore (beyond a few bland side quests and collectible items). The pacing is choppy, indicative of its easy-to-set-aside handheld origins. Bugs are everywhere, ranging from unprompted costume changes to finicky usable objects to falling rocks hanging in mid-air. Stabbing, climbing, and being stealthy are normally my jam, but within a couple hours, the missions felt routine. There were a few bright points, but overall, I was underwhelmed.

And yet, I can forgive Liberation its flaws. This game fell short of the adventure I was hoping for, but it’s worth playing for one glorious, shining reason. Her name is Aveline de Grandpré.

The setting is New Orleans, 1765. Our protagonist is a child of plaçage, a form of temporary marriage common in French slave colonies. Her father is a successful French merchant; her mother, a freed African slave. Aveline has been granted the privileges of upper class life — education, wealth, the possibility of respectable marriage. Though she will be unable to inherit her father’s shipping business, he highly values her assistance with his work, and gives her plenty of free reign in managing his assets. She buys out rival businesses and gives their slaves paid employment, setting them, as she puts it, “on the path to freedom.”

All of this is done in her spare time, of course, because her main gig is murder and mayhem. Aveline is secretly a member of the Assassin Brotherhood, sworn to destroy the insidious Templar Order (this game will make little sense if you don’t go in with at least a basic grasp of the franchise’s lore and sci-fi overtones). She’s a walking weapon, capable of executing her targets without ever being seen. She wears retractable blades in her tailored sleeves. She can take out a group of guards with her bare hands. She can scale buildings, leap between trees, swim without breaking the water. She kills with efficiency and grace. She is a spectacularly dangerous woman.

Though I was unimpressed with the gameplay, there is one mechanic I have to mention: the Persona system. As you guide Aveline through her bloody business, you risk gaining notoriety, a tiered ranking which determines the likelihood that guards will aggro. Low notoriety means a guard might glance your way, but will shrug it off if you move on quickly. High notoriety means being attacked on sight. The Persona system allows the player to mitigate notoriety, and more importantly, to access different social abilities.

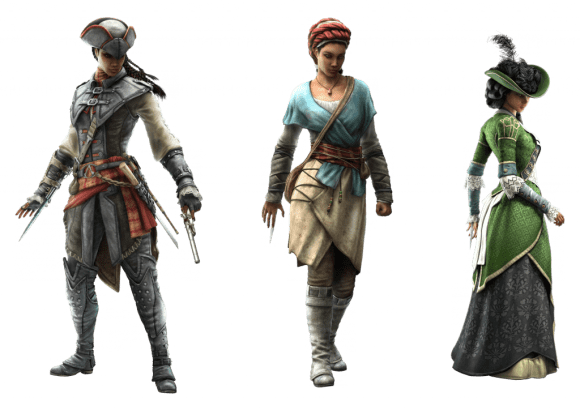

Aveline has three distinct ways she can present herself. Her Assassin garb carries notoriety no matter what, but gives her full access to her combat skills. The Lady Persona means no climbing or jumping (because, let’s be real, corsets are not conducive to parkour), but she can bribe guards to look the other way, coax them to follow her into the last secluded corner they’ll ever see, or silently dispose of them with her parasol gun. Her parasol gun. This Persona gains notoriety very slowly — she’s a lady, after all. She can get away with a lot. Quite different from the Slave Persona, which accrues notoriety for acts as minor as knocking into someone on the street. Guards need little excuse to rough up a slave. The trade-off is that in this guise, Aveline can blend into the background. Just pick up a crate, stand close to other workers, and disappear into the crowd. A fine way to escape from the scene of a crime.

Story-wise, the Persona system translates like this: Aveline is a master social engineer, able to manipulate class, race, and gender expectations to her advantage. She knows that the same townspeople who wave and call “Bonjour!” when she wears snappy green silk won’t look twice at her if she’s wearing rough cotton and carrying a broom. She knows when to flaunt her beauty and charm, and when to look down and play stupid. She wears a different face with everyone. With her family, she is spirited and affectionate. With her mentor, assertive and attentive. With her targets, menacing. Or coquettish. Or invisible.

Aveline’s malleability is further underlined by her cultural identity — or, rather, identities. She speaks with high-society polish and quips about the inferiority of Spanish wine, yet feels right at home among swamp-dwelling smugglers and runaways. She respects her African elders. She respects her French peers. She despises slave owners, but genuinely loves her father, who once owned her mother. The way she approaches her duality is complex, but this isn’t the story of an outcast. This is the story of a calculating woman who found herself with one foot on either side of a divide, and built a bridge to walk between.

The parental figures in Aveline’s life provide her with additional nuance. Her doting father, Philippe, encourages her independence, while her Assassin mentor, Agaté, disparages her impulsiveness. Her French stepmother, Madeleine, is abolitionist-minded, and treats Aveline as her own. Interesting as these characters were, none were more compelling than Aveline’s mother, Jeanne, who mysteriously vanishes in the opening moments of the game. Jeanne’s story is unraveled through her collectable diary pages, the one side quest I could not leave unfinished. Her diary begins with her struggle to become literate, and continues through her sale to Aveline’s father. I won’t give away the details, but suffice it to say, Jeanne’s feelings toward Philippe are poignantly layered. There’s fondness, yes, but I think it falls short of forgiveness.

I’ve played games that deal with themes of race and class, but I’ve never played a game that addresses them with such clarity. I’ve never seen a character like Aveline. I have no one to compare her to. She is totally unique.

Aveline’s strong characterization is bolstered by her excellent visual design. Five minutes into the game, I was struck by how badass she looked in her Assassin gear. For several hours, I was too busy muttering “wow, she looks cool” to fully realize why. There’s a key detail, one typically rare for female player characters in combat settings. Here, look at her outfit on the left:

Do you see it? It’s not the weapons, or the gauntlets, or even the flat-soled boots.

She’s not wearing boob armor.

The take-away here is not that boob armor is inherently bad. There’s a time and a place for boob armor. There’s even sensible, tough-looking boob armor (Exhibit A: Commander Shepard). But Aveline is wearing a neck-high leather doublet, without a plunging neckline or sculpted cups (in game, at least — the promo art is more busty). It’s the most obvious, practical choice for someone who needs both protection and mobility. As someone who has worn a snug leather doublet before, trust me, they don’t meld to your curves like shrink wrap. Everything gets compressed, much like you see here (an ideal thing if you’re doing a lot of running and jumping — this is why sports bras exist). Aveline’s clothing makes perfect sense in her line of work. It doesn’t make her look like less feminine, it makes her look competent. This is a woman out do to some serious damage. When I look at a female character portrayed in such a way, when I see no dissonance between her appearance and her skill set, when I think, “Yeah, that’s exactly what I would want to wear if I was in her shoes” — combine that with a well-developed personality, and you’ve got a power fantasy I can unequivocally engage with. It feels like Christmas.

Aveline never stopped feeling dominant, even when she changed into brocade and lace. When Aveline puts on a fabulous dress and a coy smile, she’s not doing it for the player. Oh, no. When Aveline flirts, it means someone is about to get played. And/or stabbed. Aveline is always in control, no matter what her appearance or her behavior. Assuming a traditionally masculine role does not compromise her femininity. Assuming a traditionally feminine role does not compromise her power.

God, I love this character.

I’ve seen little written about Aveline, which is unsurprising, given Liberation’s initially limited release and lackluster reviews. But she should be written about. This is a character bursting with fuel for critique, from as many angles as possible. My own impressions are limited to my racial perspective (that of being white) and my shamefully meager knowledge of American colonial history. I am itching to hear more varied thoughts on her, and for that, I’m glad that this game — buggy and blasé as it can be — is now available to a wider audience (Xbox 360 and PS3 owners, you’re good to go, too). Aveline deserves to be out there. And yeah, she deserves a better game. You should play this one anyway.

Becky Chambers writes essays, science fiction, and stuff about video games. Like most internet people, she has a website. She can also be found on Twitter.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]