“Don’t Read the Comments” and Taxes

It sounds funny, but...

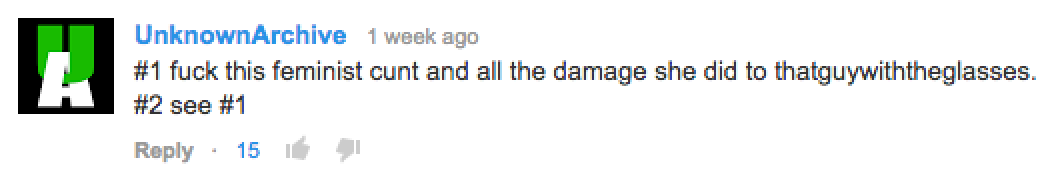

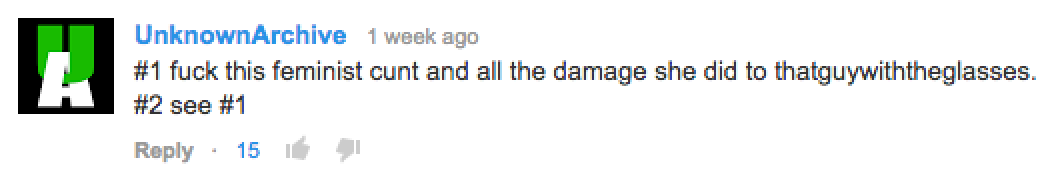

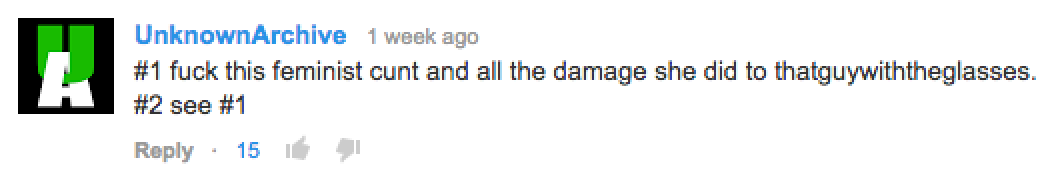

The other day, I semi-jokingly tweeted this screencap:

I found it noteworthy, because the video in question was about tax tips for self-employed people. I found it somewhat emblematic of the online experience for women; it doesn’t matter what you say, you are not welcome here unless you are existing solely for male consumption. Most people told me I should know better than to read the comments. In fact, many of the responses I received were variations on “You told me yourself: don’t read the comments.”

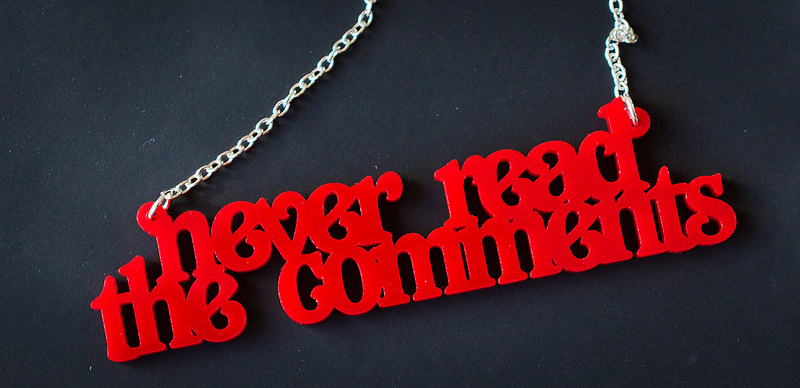

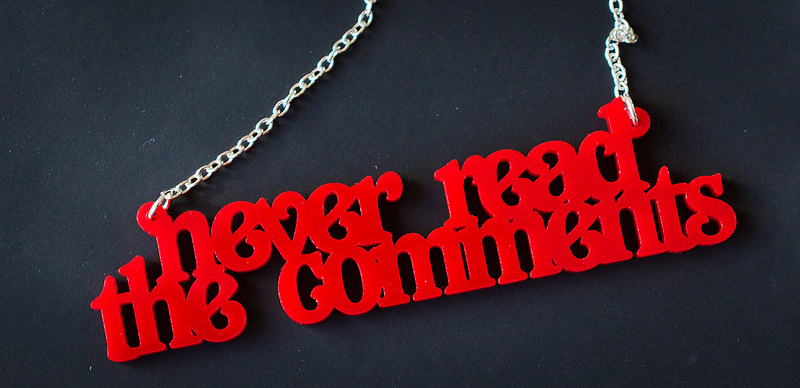

I do say that, don’t I?

I admit, this is a personal motto that I have learned to adhere to out of necessity, lest my day be ruined by a comment about the state of race/gender/robot/whatever relations in America that is so obviously wrong. It doesn’t matter if the comment itself applies to content of my own creation; it still affects the reader, whether we admit it or not. But this motto ignores one important aspect of online commenting: that comments have power. They have the power to reinforce, and they have the power to silence.

“Don’t read the comments” is a method of self-preservation, a means of individual people coping with the onslaught of foulness that so famously lies beneath the content of most unmoderated websites. This has become such an inevitability that “Don’t read the comments” has become a truism for reasonable day-to-day Internet use. Want your day not to be ruined? Want not to be drawn into a futile, bottomless debate? Don’t read the comments.

The problem with such a truism is this: who wins in the long term?

I feel like most of us are up to speed on the actual meaning of the First Amendment, but for the sake of argument, let’s clarify: Free Speech pertains to government censorship, not privately-owned publications and forums. A newspaper has the right to accept or refuse an article from one of their contributors based on a number of criteria. A website has the right to moderate comments, or not. Some do, and some don’t. It is within their legal rights to decide how best, or if at all, to go about this; after all, as I must remind people regarding my own website, they do pay for the hosting. They are not obligated, legally or morally, to host your opinion on their bandwidth. There is also a commonly accepted fallacy that website with moderation policies do so to deflect dissent—this is almost universally untrue. But if you’ve grown up in a system that rewards toxicity, it’s easy to see your own abusive language as really just reasonable dissent.

Nearly every website you visit—this includes YouTube—is privately owned, and if it has enough traffic, it probably has a clearly-outlined terms of use policy by which all commenters are expected to abide. This does not guarantee anyone who uses this service the right to say anything. Free Speech is protection against government overreach, it is not a license for you to say whatever hateful thing you want on a privately owned website with a clearly-outlined comment policy.

There is a common tendency to conflate “censorship” with “not being able to say what I want on exactly the platform I want.” Free speech guarantees your right to speak. It does not guarantee your right to say what you want in whatever forum you wish, or to be heard.

With this in mind, let us examine spaces where the common wisdom “Don’t Read The Comments” applies—if the space does pertain to, for instance, women’s issues, many commenters feel compelled to remind both the content creator and any reader that should stumble across it that women are not welcomed by a large swath of the Internet. And perhaps you might opt out of exposing yourself to this. Maybe you “Don’t Read The Comments.” But that doesn’t mean that everyone will follow the same philosophy.

Comments become an inevitable part of the modern experience of online media consumption. “Don’t Read The Comments” may be a valuable personal motto, but it does nothing to rectify a systemic problem if the system rewards what is effectively hate speech.

YouTube has an algorithm that promotes the most heavily engaged comments, and unfortunately the most heavily engaged comments are often the most vitriolic. Vitriol and hate speech on the YouTube algorithm are rewarded. This is unfortunate, as it does not necessarily reflect the reception of a piece of media for the majority of viewers. But it can affect the perception of that piece of media, and the way it is viewed by the consumer. This is the main reason why Popular Science decided to get rid of their comment section altogether—comments change the way you see things. Science says so.

For instance, if a young girl sees me talking about taxes for eight minutes, and then sees this:

What lesson is she going to take from that? About not only how women’s voices are perceived in online spaces, regardless of what subject they talk about, but how toxicity under this system is rewarded?

There is also an increasingly accepted fallacy, a cousin to “don’t read the comments”, if you will, that it’s just “how the Internet is.” That abuse against historically marginalized groups should be accepted, because, hey, everybody is abused equally here (a categorically untrue assessment, but there are many who genuinely believe it.) That in order to earn the right to use the internet one must first bathe in the fires of sexism, racism, or misogyny and come out unscathed, because “that’s how the Internet is” and to brave the Internet is to implicitly accept this agreement. To challenge it is to deny the Internet’s Internet-ness, its infallible status quo.

I also often get variations on this comment: “I’m glad you have such a thick skin and have learned to deal with it. But I couldn’t do that.” They are always from girls. Always.

That is a problem.

This isn’t fucking Mad Max. This isn’t some post-apocalyptic wasteland where we must cannibalize our friends and loved ones in order to survive. This is the Internet, a modern means of discourse, nothing more, nothing less. The Internet should not push “only the strong survive”—if this is the case, inevitably the strongest will be those who see the least oppression in the real world. The people who have the least voice in society have yet another venue for discourse snatched from them. They cannot participate in a societal dialogue because that dialogue has been dominated by pure, unchallenged status quo-fellating. And what can you do? “Don’t read the comments,” I guess.

“Don’t Read The Comments” may be good day-to-day advice, but that doesn’t mean that the discussion should end there. Only the people who are saying the most toxic, hateful things assert this idea that comments sections are a right, not a privilege. And considering it is they who are dominating the discourse, this need be examined. Why else would the truism “Don’t Read the Comments” even exist?

I turned off the comments altogether on my second YouTube channel, but is that really the solution? That if we are to avoid toxicity on any subject, no matter how minor the controversy, we are to take away the privilege altogether and proclaim, “this is why we can’t have nice things”?

It isn’t as simple as encouraging all websites to adopt strict moderation policies, but to examine the system in which toxicity is rewarded with attention. The most toxic people in these comments sections believe that they are owed attention, and there is no surer way to get it but on acting on their ugliest inclinations.

I may not read every comment for my YouTube videos, but there are people who do, and internalize them, and see, this is what happens when a woman dares simply to exist in a public space. Remember, this:

was in response to a video about self-employment taxes in the United States. Not once was gender mentioned.

Toxic commenting policies are a much greater enemy to true free speech than moderation policies. They shame into silence those who already have the least voice in society, and they terrify and intimidate those who do dare to speak.

Even if it is on something as innocuous as taxes.

Lindsay vlogs on various topics nerdy and nostalgic on YouTube, co-hosts irreverent book show “Booze Your Own Adventure,” and is co-founder of ChezApocalypse.com. If you don’t mind your timeline flooded with tweets about old cartoons, dog pictures and Michael Bay, you can follow her on Twitter.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]