When I first decided to do this article, I was naive. With all the modern resources at my fingertips, I thought finding information on the ladies behind animation would be super easy. “Oh, you sweet summer child,” has run through my head a few times, as I struggled to find even the most basic pieces of information. Standard books used for animation history classes barely mentioned women in passing, much less their achievements.

Because of the technical nature of animation, there is an underlying sense of sexism which is not unlike the sexism that exists in the tech space. This is true even today, where it’s not uncommon to be one of a handful of girls within a studio setting. The lack of notable female animation professionals within history only reinforces this assumption that it is ‘boys club’ industry. As a result, the names of women who have moved the industry forward have faded. This is my attempt to bring them back into the spotlight.

“If a woman can do the work as well, she is worth as much as a man. The girl artists have the right to expect the same chances for advancement as men, and I honestly believe they may eventually contribute something to this business that men never would or could.” – Walt Disney

talking about Frozen, 1941

I remember when I realized cartoon characters weren’t real…and it was all Walt Disney’s fault.

I was five and I was sick. In her wisdom, my mom brought home a stack of cheap video rentals to keep me entertained. One of those tapes was old footage of a guy claiming to be Walt Disney himself, and he was talking about a machine called the multiplane camera. He used Mickey Mouse to make an example at one point and showed us Mickey was really a series of drawings (link for the interested). I was amazed Mickey Mouse wasn’t actually real, but that someone literally drew him to life.

Of course telling my friends about this ended as well as telling any five-year-old that Santa and the Easter Bunny were a sham. They were devastated, but I was transfixed by the idea that maybe one day I’d draw something to life too. I wanted to be an animator more than anything.

While we idolized all these princesses on screen, it seemed like all the people who brought them to life were men. I looked up to the likes of Glen Keane (character animator for Ariel and Pocahontas) and Andreas Deja (character animator for Triton and Scar) but often wondered where I would fit in. Little did I know, women had been part of the industry for years.

Some of the information here may be inaccurate, not for lack of research, but for lack of solid resources. Many women in the early days even used male versions of their names, or weren’t mentioned at all. As a result, the stories of these artists shimmer dimly through stories from industry older timers and the occasional mention in film credits.

1899 – 1981

Lotte Reiniger was the first female animator and animated feature director. Period.

This German native was the foremost pioneer in silhouette animation, and made over 40 films using silhouette puppet figures. She anticipated Disney and Iwerks by ten years: taking on fairy tale-based stories, invented the first ever multiplane camera and co-founded her own company Primrose Productions in 1953.

Her most famous works include The Adventures of Prince Achmed, Carmen and Papageno. In 1972, Reiniger won the Filmband in Gold Deutscher Filmpreis and the Great Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1979.

- The only pictures of Friedman I could find are her self portrait doodles!

1912 – 1989

Lillian Friedman was the first female studio animator with a screen credit. She started as an inker (someone who inked individual drawings onto clear celluloid sheets by tracing the animators sketches) for Fleischer Studios, which was famous for Betty Boop, Popeye and the early Superman cartoons. Her talents were quickly noticed by animator James Culhane, and with his guidance Friedman became the first female studio animator in 1933. Her first animation work (uncredited) was said to be in the Popeye cartoon Can You Take It, which is basically Fight Club with Popeye. Out of the 11 titles Friedman worked on, she was only credited for six.

Things seemed fine for Friedman until 1937, when Fleischer animators went on strike. Friedman, like most women of that era, couldn’t afford to give up her job even on a temporary basis. So, she walked right over the picket line and got back to work. Of course, this pissed off a lot of her coworkers. Once the strike ended, Friedman was constantly harassed for her choice to continue working and for being a woman in a man’s job. She looked for work elsewhere, even applying to Disney, but had no luck. In 1939, after seven years of solid work heading the in between department and animating some of the era’s most beloved characters, Friedman left the animation world for good.

- She basically animated your parents’ childhood.

1905 – 1984

Remembering when he first hired her, Producer/Director Walter Lantz said,”most producers thought women could only draw birds and bees and flowers. They were wrong, of course.” The second female studio animator in history was hired on by Walter Lantz Productions, and started off as an inker. In 1934, LaVerne Harding became the second woman in animation history to receive an onscreen credit for Wolf! Wolf!, an Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon. Harding worked at Lantz Productions for 26 years animating Oswald, Andy Panda and Woody Woodpecker cartoons.

Even after leaving Lantz Productions she went on to animate for The Pink Panther, and many of the Looney Tunes characters. Harding’s work included six Academy Nominations and one winner (The Pink Phink in 1964), though she was never recognized for her contributions. “She was like a goddess because nobody else even got to be an in betweener,” said Martha Sigall an ink and paint assistant. In 1980 Harding won a Winsor McCay Lifetime Achievement Award, one of the highest honors an animator can achieve. Out of 161 Winsor McCay awards she is one of only 9 women to receive the honor.

- Made Disney go from gag ridden silliness to the moving storytelling we love.

~1901 – ????

The first woman Walt hired for the story department, Bianca Majolie’s first project was Pinocchio. When the Hollywood Citizen News got word that Disney had hired their first female artist they did an expose on her…BUT NEVER MENTIONED HER NAME. On a copy of the article passed around the office, Majolie sarcastically wrote, “Who is this girl?”

Majolie was responsible for much of the early concept work for Peter Pan, Cinderella and Fantasia’s Nutcracker Suite. She’s most well known for creating Silly Symphony’s Elmer Elephant, who is often argued to be the inspiration for Dumbo. Animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston (two of the original Nine Old Men) credited Majolie for elevating the art of Disney storytelling, “We could not have made any of the feature films without learning this important lesson: Pathos gives comedy the heart and warmth that keeps it from becoming brittle.” Majolie was unceremoniously fired in June of 1940, her work handed off to another story artist, Sylvia Moberly-Holland. Majolie never returned to animation.

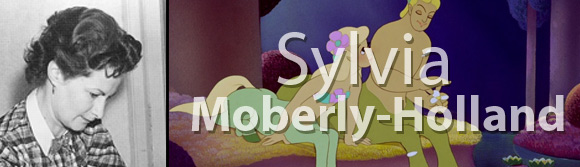

- Kahleesi of Centaurs!! It is known.

1900 – 1974

Excellent artist, accomplished musician and world renowned cat lover (no, seriously, she was a pioneer for the Balinese cat breed), Sylvia Moberly-Holland was the second woman hired by Disney’s story department. After seeing Snow White for the first time, Moberly-Holland left the theater with stars in her eyes and a dogged determination to work for Walt. Her dream was realized when she was hired in 1938 and put to work on Fantasia. Her concept art inspired Fantasia’s iconic Pastoral Symphony (aka OMG CENTAURS) and the Waltz of the Flowers segment.

She became Disney’s first female story lead with the fairy sequence as well. This job was fraught with drama, as her male staff resented taking orders from a woman. Due to the excessive homophobia of the period several on her team transferred from working on the “fairy” sequence after getting harassed one too many times (hey, rampant homophobia at Disney, who knew? /sarcasm). Even with a constant rotation of artists, Moberly-Holland lead her team to make one of Fantasia’s most beautiful sequences. With all of her duties, she was the closest any woman came to being a director at Disney until Jennifer Lee on Wreck-it Ralph. She was laid off at the end of WW2, but continued creating art until her death in 1974.

- The woman who made my cousin terrified of dogs.

1916 – 1990

Retta Scott was the very first woman to animate for Disney. As a CalArt’s student she spent a lot of her free time at the local zoo sketching animals. This hobby paid off when she was hired as a story development artist for Bambi in 1938. Remember those terrifying dogs that chase Bambi’s girlfriend Faline at the end? That was the first animation work Scott ever attempted! Fellow animator, Frank Thomas said she had an astounding ability to draw animals. According to Marc Davis (another prominent Disney animator), “No one matched her ability in drawing animals from all angles, which made the dogs frighteningly realistic.”

Scott continued working for with Disney during WWII on the propaganda films, but once the war was over, like so many other ladies in men’s jobs, she left and became a freelancer. One of her most prominent gigs was The Big Golden Book Edition of Disney’s Cinderella. Her screen credits include Disney’s Bambi, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Nepenthe Productions’ The Plague Dogs. Scott was posthumously named a Disney Legend in 2000.

- It’s a small world after all~! It’s a small world after all~!

1911 – 1978

Despite a tumultuous and destructive personal life, Mary Blair rose to become one of the most influential artists in Disney history. Starting out as a Disney concept artist in 1940, Blair’s unique style and mastery of color gave Disney films such as The Three Caballeros, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan their iconic look. Frank Thomas said this of Blair: “[She was] the first artist I knew of to have different shades of red next to each other. You just don’t do that! But Mary made it work.”

It was after Peter Pan that Blair resigned from Disney and in the coming years she lived out a troubled life dealing with domestic abuse and her own alcoholism. However, Blair’s greatest claim to fame was created in the midst of these personal challenges – the It’s A Small World attraction. Blair designed the costumes, sets, locations – literally the entire ride was built around her designs. The attraction was born through some of her hardest times and still manages to bring joy to people world over to this day. In 1991, Blair was posthumously given the Disney Legend Award, and in 1996, posthumously given the Winsor McCay Award. On her birthday in 2011, Google paid her tribute with a Google Doodle.

- A wicked sense of humor and Canadian to boot!

1923 – 2013

A Canadian greeting card artist, Eunice Macaulay went from seemingly nowhere to becoming the first female animator to win her own Academy Award for her film Special Delivery (1978). The short film, which was produced in part by Canada’s National Film Board, is a dark short full of dry humor about a mailman’s untimely death.

Throughout her career Macaulay worked on more than 25 short films in various roles of production from animator, director, writer, producer and more. She worked for the Canadian National Film Board from 1973 to 1990, and remained an animator and artist until her death in 2013.

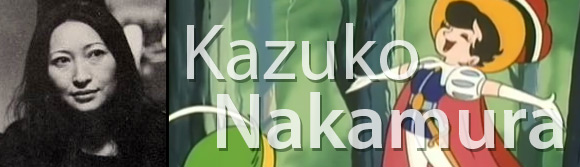

- She made women sexy without their boobs doing gymnastics.

???? – ????

As one of the first – if not THE first – female Japanese animators, Kazuko Nakamura is considered by many to be the mother of modern anime. Despite this, very little is known about her in the US. What we do know is she started her career in 1956 at Toei Doga. She soon transferred to Mushi Pro in 1960 where she became the first female animation supervisor (in Japan the title is called ‘animation director’) for an entire TV series, working on the first shoujo anime Ribon No Kishi (Princess Knight).

With another jump in positions, Nakamura started working for Mushi Pro’s Animerama and produced the majority of animation on their first two feature films, 1001 Nights and Cleopatra. She is well known for making the female characters she worked on authentic in their femininity, devoid of the oversexualization often created by male animators. She was a powerhouse animator throughout her career and one who managed to bring just the right touch to the women she drew to life.

- Her work made us all cry at least once.

???? – 2007

Hailed as the second female Japanese animator, Reiko Okuyama was a sickly kid who often spent her days in bed. To pass the time she turned to drawing and by the time she went to college her skills were OVER NINE THOUSAND! Thinking the animation house was a children’s book publisher, she applied to Toei Doga in 1957. She was hired as an in betweener and in 1959 was promoted to 2nd key animator on Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke (Magic Boy).

When she became a mother, it was expected that she would step down to become a homemaker, but Okuyama wasn’t having that. Of course this brushed her bosses the wrong way (“Working and parenting?! THIS IS INCONCEIVABLE!”). Let’s just say her bosses got pretty pushy about it, right down to threatening her husband’s job too. So, she left…and came back with the industry unions backing her up. With their help, Okuyama won the right for Japanese women to balance work and family without sacrificing their careers.

Eventually she became head animator at Toei Doga where she served as an supervising animator on 30,000 Miles Under the Sea and Toei Doga’s version of The Little Mermaid. She left Toei Doga shortly after that going on to work as a freelance artist and teacher. Her notable works include Grave of the Fireflies, Puss in Boots and The Little Norse Prince. She continued to produce and teach animation until she died in 2007.

- Bakshi’s funny girl and full time animation badass!

???? – ????

Brenda Banks’ career took off in the mid 70s when she straight up walked into Bakshi Productions, was marched into Ralph Bakshi’s office and declared she wanted to work for him. Bakshi was so impressed by her guts, he put her to work on Wizards, where she became the first black female animator. She continued working for Bakshi on The Lord of the Rings, but left after finishing Fire and Ice.

Banks went on to work with Warner Bros Looney Tunes, Hanna-Barbera’s The Pirates of Dark Water and into the realms of FOX’s The Simpsons. She was hailed by Bakshi as “one of the funniest – most hysterical animators that ever walked into Bakshi Productions.” Unfortunately, she seemingly disappeared after her last credited work on King of the Hill in 2005. You can watch Bakshi geek out about her here.

Honorable Mentions

While the ladies above were pivotal, they weren’t the only ones to make waves in the industry. Below you’ll find a few notable ladies who blazed their own trails.

Elizabeth Case Zwicker – Poet, feminist and artist “Big Liz” animated the birds, forest animals, and the wine guzzling Jester in Sleeping Beauty. Her efforts afforded her $32 to $35 a week while working for the Mouse. As the majority of ladies were in Ink and Paint at the time, drawing birds was a big F-ing deal. Floyd Norman (the first black animator hired by Disney) has a great post about her on his blog.

Tissa David – A Romanian born American animator whose career lasted about 60 years. She was the second woman to direct a feature film with Bonjour Paris. David is famous for her design and animation of a major lead with Raggedy Ann in Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977).

Retta Davidson – During WWII, many of Disney’s animators were drafted into military service. So Disney fixed their labor shortage by turning to the ink and paint girls. Davidson, along with 10 other ladies from Ink and Paint, were pulled into the animation department in 1941. Her credits include The Fox and the Hound, The Great Mouse Detective, Heavy Metal, and Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings. Sometimes credited as “Redda” she is often confused for Retta Scott.

It’s upsetting that these are just a handful of some of the amazing ladies history tends to overlook. I wrote this thinking it would be fun to educate people about women in animation history, but what I really learned is just how little there is to know. While I’m skeptical that we can add to our understanding without access to a TARDIS, I do know there’s something we can do.

We as women have to own up to our triumphs. This amorphous onset of fear induced modesty has got to go. Moving forward, it’s time for women to claim the history we’re making.

In the next installment, I’ll talk about the modern women who’ve been breaking the animation industries’ celluloid ceiling.

By day Carrie is the co-creator, artist and production coordinator of Kamikaze. By night she’s a writer, khaleesi of corgis, and budding comic nerd. Occasionally she takes pretty photos. A devoted lover of film, animation and storytelling, Carrie is feared wherever books are sold, and enjoys the company of animals, geeks and artists equally. Feel free to send questions, comments or adorable animal pictures to her on twitter or her tumblr.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Jun 4, 2014 03:30 pm