I am an unashamed horror movie junkie. Good horror movies, bad horror movies, horror movies from the 1970s with barely coherent plots and implausible dialog—I love them all. If it’s spooky, gory, or scary, I’ve probably seen it, which means that a certain amount of desensitization has set in. I’ve come a long way from the 15-year-old who had to sleep with the lights on and the mirrors covered after watching The Ring. I have a sixth sense for anticipating jump scares. I am that annoying person who will call out a plot twist seconds before it happens (“…annnd the closet door swings open,” “Cue shadow reflected in the window,” “Yup, she’s going to go down into the basement. Of course she is. Well done.”) All this to say: I am difficult to scare.

It’s tricky, being a horror enthusiast and a feminist. Despite the fact that the genre was pioneered by women, it’s rare these days to see a scary movie with a well-rounded female character. Horror films are full of regressive (often downright misogynist) tropes that relegate women to damsels, hags, and vengeful specters. There’s a strong link between sex and horror, and when women appear on-screen, their presence usually amounts to the topography of their bodies—dismembered or complete—frequently in the grip of a sadistic, destructive monster. I often find myself apologizing for my love of horror, trying desperately to justify why these films are good.

I don’t have to justify The House on Pine Street. Not only did it have me lying awake until sunrise with an elevated heart rate, jumping at every creak and groan of the house, but it also had a female protagonist who spends the whole film fighting for agency over her life and her body—without accidentally-on-purpose bearing her naked breasts to the world. And it’s a genuinely good film—from the direction to the sound design to the stellar cast performances.

Expectant parents Jennifer (Emily Goss) and Luke (Taylor Bottles) move back to Jennifer’s hometown in rural Kansas to be closer to her mother after Jennifer suffers a mental breakdown. As expected, they move into a spooky historic home that soon starts to terrorize Jennifer. Boxes move by themselves, the closet door opens and closes on its own, and in one particularly unsettling scene, a loud and repeated knocking comes from the front door even though there is nobody outside. As if this wasn’t upsetting enough, Jennifer’s overbearing mother and her well-meaning but generally absent husband (neither of whom witness any of the strange occurrences) both seem to think Jennifer is just going crazy again.

“Sorry, honey, I think you might be a little too crazy to walk down this well-lit hallway by yourself.”

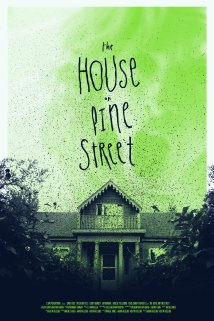

I thought I knew what I was getting into with The House on Pine Street. The movie poster looks similar enough to every other haunted house movie you’ve ever seen; The Conjuring, House on Haunted Hill, The Amityville Horror—creepy house is creepy, there will probably be ghosts, someone will die violently, lather, rinse, repeat. I went into it with the assumption that it would be a stock-standard genre piece with a low budget that would, at least, force it to get a little creative with its terror (CGI is expensive). What I got instead was 111 minutes of the most tense cinematic experience of my life, with scares that escalated rapidly and built on top of one another to create a fever-pitch anxiety that never truly broke.

The House on Pine Street does rely on genre tropes—sort of. First-time writer/director twins Austin and Aaron Keeling and writer Natalie Jones have described the film as “a love letter to the horror genre.” They’ve seen every haunted house movie on the market, and you can tell. THOPS plays with its audience by placing them in a familiar setting, then yanking the rug out from under their feet. “We were extremely conscious of horror movie and haunted house tropes, and we wanted to employ them as much as possible so that we could shake them up a bit,” the THOPS crew told me in an interview. Well, mission accomplished, friends.

The main shake-up is the character of Jennifer herself—one of the most well-rounded, believable female leads I’ve seen in a horror movie. Throughout the film, the audience is kept closely in Jenny’s POV; in an early scene, the camera holds an uncomfortable close-up on her as she starts to have a panic attack at her own housewarming party. The sound muffles and deadens as if she’s being held under water, and we watch her struggling to breathe and calm herself. For anyone who has ever experienced intense anxiety, this scene is hard to watch.

We know from the outset that Jenny is troubled, that she’s at best ambivalent about her pregnancy, that she hates her mother, and that she most definitely did not want to move to Kansas. Here, the filmmakers have resisted the temptation to make Jenny a single-note character—the soft, kind motherly figure or the hard-headed harpy. She’s relatable because she’s human; she’s scared even before she sets foot in the house—frightened of being a mother, maybe even frightened of growing up. “There are some qualities to her character that we were very adamant about including in order to make her seem like a more nuanced, complex human being,” the THOPS crew said. “This was another case of subverting tropes. In most haunted house movies where a character is pregnant (as Jennifer is) or has children, the focus of the character almost always ends up being to protect the children. To save the kids, to keep the family away from harm … We wanted to subvert the “protect the family” themes of many haunted house movies by making Jennifer more concerned with her own desires and safety than those of her unborn child.”

If you’ve ever yelled at the TV while watching a horror movie, then Jennifer is the protagonist of your dreams. She does everything right. She never doubts herself. She lets her husband know about the weird supernatural happenings almost immediately and continues to report the strange things she’s experiencing even when she’s met with stern disbelief. As the story unfolds and the ghostly presence intensifies (there’s one particularly horrifying scene that takes place in a shower, where a familiar yet incorporeal hand gropes Jenny’s distended, pregnant belly), we learn that Jenny might not be a completely reliable narrator. Yet, it’s impossible not to root for her, even when her mind seems to be unraveling; at every turn, Jenny’s attempts to get help and support are dashed. The filmmakers go through the expected motions in deploying the Best Friend, the Psychic, the Well-Meaning Neighbor, and even Some Spooky Mute Twins, but nobody has any answers for her besides, essentially, to get over it.

THOPS dashes expectations in a number of other exciting ways. Most of the scares happen during the daytime, and absence is used effectively to ratchet up terror rather than give a name and a face to whatever is lurking inside Jenny’s house. “We really feel that many horror films lose their scare value when they start to load themselves down with huge CGI sequences and crazy special effects,” the crew told me. “[Those movies] lose so much scare value once they tell you exactly what is happening and who the villain is … we really believe in the power of absence when creating suspense.”

In this respect, THOPS has more in common with classic works of horror literature than it does with generic blockbuster fright-fests. The crew were inspired by books like Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby. The house itself is positioned as the main antagonist, drawing from early gothic horror like Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. The audience is never allowed to feel safe, and the film generates horror by steadfastly refusing to supply answers or quick fixes. “We don’t supply clear-cut answers to the supernatural occurrences, because it just isn’t realistic to us to do so,” the crew told me. “Sometimes there are no answers, and sometimes it’s what we can’t explain that is the most frightening.”

THOPS has its LA premiere on November 19th at Laemmle’s Music Hall 3. You can grab tickets online, and keep an eye on their official website for upcoming screenings in your city.

Kia Groom is an Australian writer, editor, and publisher currently residing in New Orleans, Louisiana. She’s published numerous essays, poems, and short stories, and runs the intersectional literary magazine Quaint. You can find her on twitter @whodreamedit and on her website, kiagroom.com.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Nov 18, 2015 01:39 pm