Where Are the Radical Politics of Modern Star Trek?

This year is a big year for Star Trek. There’s a new movie, Star Trek Beyond, on the horizon, details about the new TV show coming in 2017 are trickling in, and it’s the 50th Anniversary of the franchise. It’s a year for us to look forward to the future but to look back, as well, and remember what made Star Trek special to begin with.

Though the wonder of the Enterprise and the humor of Kirk, Spock, and Bones were essential to what Trek has always been, the show has been political since its origins. The first interracial kiss broadcast in the U.S. was during a Star Trek episode. Stories consistently tackled topics of war, sexuality, and racism, always allegorically tying these themes back to the politics of the time.

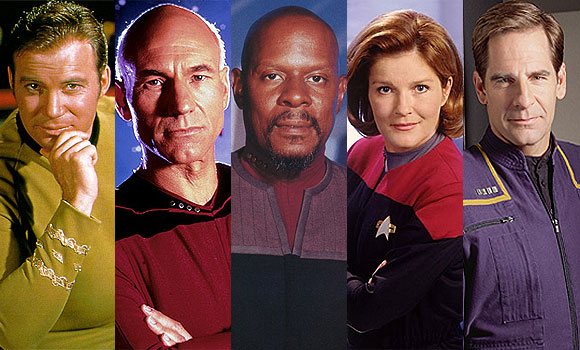

But the Trek we’ve seen in recent years—though the action, the humor, the characterization, and in many ways, the cosmic wonder have remained—has become depoliticized. The new film series, started by J.J. Abrams in 2009, has been wonderful entertainment—and in many ways wonderful Star Trek—but has featured little to no commentary on the many issues facing society today. In many ways, especially after full TV runs featuring a black lead in Captain Sisko and female lead in Captain Janeway, having Kirk back at the helm feels like a step backwards.

The identities of the original Enterprise crew were incredibly radical … in 1963. Today, a principle cast featuring mostly white men and token people of color in mostly secondary roles should not be considered diverse. That, coupled with whitewashed casting (no, we haven’t forgotten that Benedict Cumberbatch played a whitewashed Khan) and unnecessary bikini shots leave much to be desired as far as the radical politics of Trek. Though one could argue these cases were minor slip-ups (which many of the writers and producers have since apologized for), it’s clear that asking the big questions Trek used to consistently pose is not a priority for this production team. This doesn’t mean they’re terrible films or even terrible Trek films—Star Trek: First Contact and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan were great Trek but lacking in political commentary—but when this is the only Star Trek available, when this is essentially what Star Trek is for the modern era, there’s a problem.

One could argue that this has always been the case with Star Trek’s adventures in Hollywood. Saving the whales in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home or fighting against the assimilating Borg in First Contact are far tamer forms of advocacy than discussing an allegorical proxy war in the midst of the Cold War era with the introduction of the Klingons in “Errand of Mercy” from the original series or deconstructing the notion of gender, such as in “The Outcast” from Star Trek: The Next Generation. But these justifications feel somewhat forced in light of the big push for diversity among the primary cast of that other Star-related franchise. Though diversity isn’t enough—ideally we want identities not only represented but discussed in a nuanced manner within the narrative—it’s a good start, and it’s sad to see Star Trek fall behind when it was once a leader in bringing marginalized identities onto the big and small screen.

But this year offers up an opportunity to bring the radical politics of Trek back to the forefront. Paramount and CBS now have an economic incentive to look back to the franchise’s past—after all, much of the memorabilia and concert and movie tickets that they’ll make money off of this year will be fueled by nostalgia. When we look back and reflect on what Trek used to be, we cannot let that be depoliticized as well. Perhaps by ensuring that those in charge of making more Star Trek are aware of this legacy—both the creative and corporate parties—we can see those radical politics return, updated for the modern era.

There’s a lot to hope for in this regard. With Bryan Fuller (who has already said that Angela Basset would be his dream captain), Nicholas Meyer, and Rob Roddenberry on board for the upcoming TV series, it’s likely that we’ll at least get a diverse principal cast, and hopefully politically complex storytelling, as well, but that isn’t something we should take for granted. Even the best creative teams can be stifled under corporate influence or attempts to reach out to an imagined audience with different demographics and desires than those of most modern television viewers.

Science fiction is at its best when it reflects our current world, when it causes us to pause and reconsider our assumptions about society as it exists today. It challenges the status quo and what is defined as possible, asking us to imagine a better world than what we currently have. Star Trek, when at its best, lives up to this vision and asks more from its audience than simply their enjoyment. If we—as fans, or even people interested in more radical fiction on our televisions—make it known that this is the kind of Trek we want to see for the next fifty years, perhaps it can become a reality, and Star Trek can once again go boldly where no show has gone before.

Frank Tavares is an English and Astronomy student at Amherst College who enjoys acting in theatrical productions, writing and editing for AC Voice, and ruminating on the intersections between the sciences and humanities. He’s an avid Trekkie, comic book reader, and gamer who enjoys writing non-fiction, fiction, and poetry. Find him online at ACVoice.com or on Twitter @frankrtavares.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]