No Escape and Erasure Films: Hollywood’s Version of #AllLivesMatter

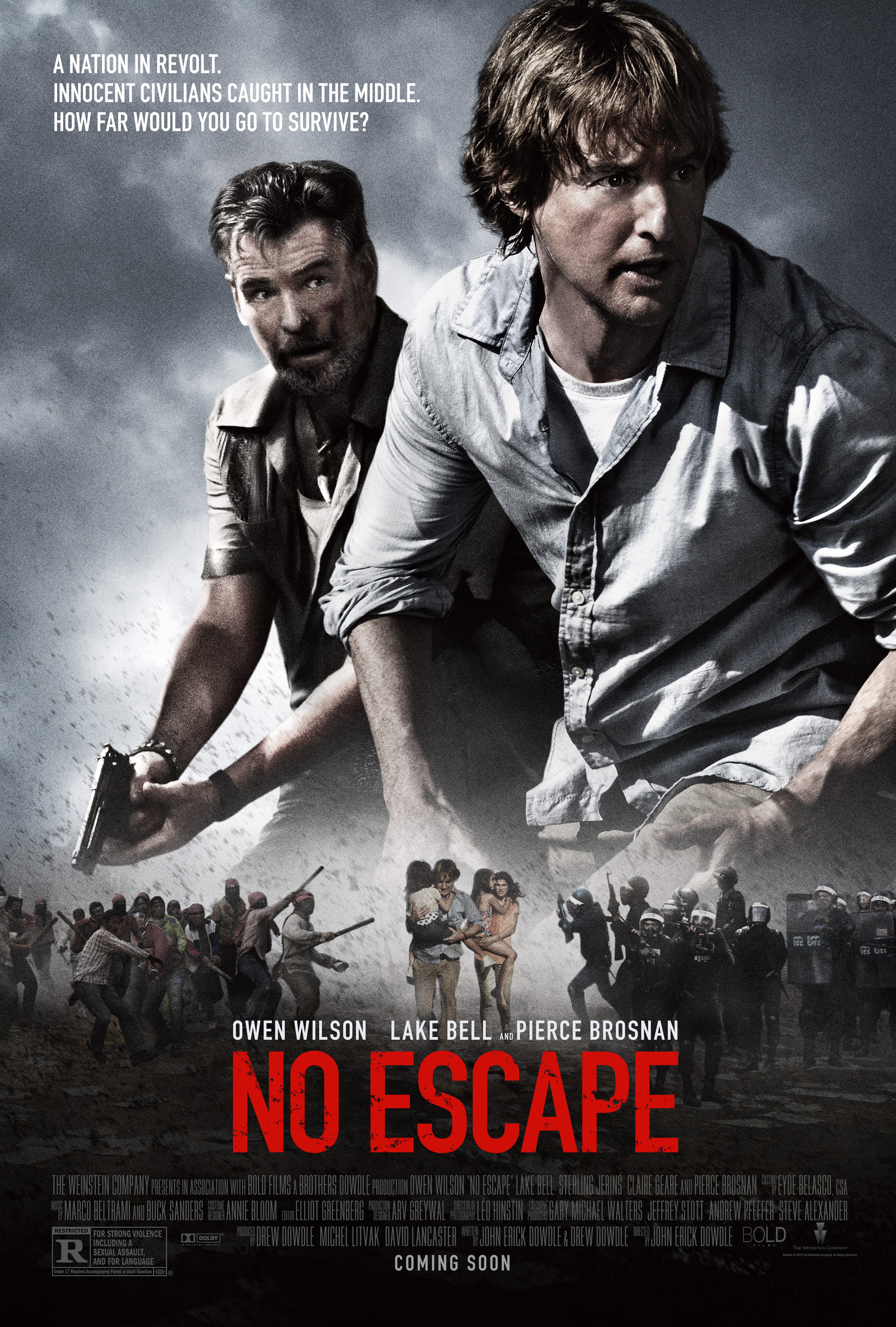

Many moviegoers are probably gearing up to see Hollywood’s latest disaster film, No Escape. The film, starring Owen Wilson and Lake Bell, features an American (read: white) family relocating in Southeast Asia. But somehow, they find themselves in the middle of what the film’s synopsis calls “a violent political uprising.” They have to escape the fray by the skin of their teeth and search for refuge. This is a typical Hollywood movie; since the film is all about the thrill of survival, we know the people will be safe in the end. The film is also a typical Hollywood film in that it places white characters at the center of a film that features the suffering of non-white characters as set dressing.

No Escape is just one of a series of movies in which the emotional experiences of white characters in a foreign, non-white country overshadow the experiences of the country’s actual citizens. In these films, the white outsiders get treated as viable characters and the non-white residents get treated as stereotypes or emotional props. To me, there’s a biased, “All Lives Matter” feel to films like these. Similar to how, in the wrong hands, “All Lives Matter” can be used as a crutch for “white fragility” when it comes to talking about race, films like No Escape seem to also buoy the same fragile look at race and privilege. Just like with the blind usage of the #AllLivesMatter hashtag, there’s a tendency for films like No Escape to exercise less sympathy for the native characters who are actually in the same peril, if not moreso, than the white leads.

White characters as the default

No Escape continues the Hollywood tradition of using white characters as “default” characters in films. No Escape’s story of a family being caught up in the center of violence isn’t a “whites only” story. Any family of any background could have been used to tell this story. Also, No Escape isn’t based on any true story involving a white family, so any reasoning that might exist for casting an all-white family is even shakier.

Hollywood has a long history of doing this. Some of the films of 2015 that do have all-white or majority white casts, such as The Gift, Ricki and the Flash, the upcoming film The Visit and many others don’t really depend on the races of characters to get the story across. Yet, all of these films feature a severe lack of diversity. You don’t just have to look to 2015 for films like these either; for as long as Hollywood’s existed, films across all genres have regularly featured white characters over non-white ones. Example: every Woody Allen film.

White characters are also used as the default in films that aren’t even about white people. One example among many is 21, which is based on the real life story of the MIT blackjack team, had Jim Sturgess play a character based on Jeffrey Ma named “Ben.” Another is nearly every interpretation of Cleopatra in film, including the likes of Claudette Colbert and Elizabeth Taylor playing the Egyptian-Macedonian queen. One of the most recent instances of whitewashing is Emma Stone playing a hapa character Allison Ng in Cameron Crowe’s critically-panned Aloha. Stone is clearly not part native Hawaiian, but she was cast to play Ng even though there were several other hapa and multiracial Asian actresses that could have taken the part.

One of the films that put whitewashing back on the map is 2012’s The Impossible, which, like No Escape, is a family-based thriller set in South Asia. The Impossible is based on the true story of Spanish doctor and motivational speaker María Belón and her family’s harrowing escape from the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami while vacationing in Thailand. However, Naomi Watts and Ewan McGregor were cast as Belón and her husband, respectively. To be fair, Belón stated she personally wanted Watts to play her because of her love for Watts’ acting. But that didn’t stop many outlets from wondering why the film still featured white main characters. The Gwinnett Daily Post’s Michael Clark wrote in his review that the film “literally whitewashes history. Of the nearly quarter million people killed by the tsunami, less than 10 percent of them were non-Asian and even fewer were Caucasian. By focusing their attention on a privileged (and fictional) WASP family from England, [director J.A. Bayona] along with screenwriter Sergio G. Sanchez…rob the movie of any authenticity.”

It’s not as if white actors shouldn’t get race-neutral roles, but why does it seem like the majority of race-neutral and non-white roles go to white actors? The answer seems to be the idea that a character’s ability to connect with an audience is racialized. Let’s go back to Woody Allen for a second. Allen’s reasoning for not hiring any non-white actors is illuminating and shows the basis for how Hollywood perceives white and non-white characters. As he told the New York Observer, he won’t hire a non-white actor “…unless I write a story that requires it.” He went on to say “You don’t hire people based on race. You hire people based on who is correct for the part. The implication is that I’m deliberately not hiring black actors, which is stupid. I cast only who is right for the part.”

This pretzel logic is what the movie industry uses every day to justify their lack of diversity in films and the practice of whitewashing. Sure, hiring people based on race isn’t always the best method. But if you’re only hiring white people for race-neutral characters, what can people assume? It’s not that only white actors are “the best for the part,” which is something Hollywood likes to throw around. The truth is that there are undetected biases at work and are legitimized as “doing business.”

The falsehood of picking “who’s right for the part” also bleeds into another bit of pretzel logic Hollywood uses on a regular basis. To the industry, relatability and marketability are based on race.

If you read entertainment news outlets as frequently as I do, you might have come into contact with the industry terminology of “casting for the overseas market.” Studios often feel like overseas markets only respond to white actors in films, so they resist casting non-white actors. None of that makes sense. Hollywood is an industry based on white supremacy; remember that the first Hollywood blockbuster was Birth of a Nation, which tells the fantasy story of the KKK saving white virtue from animalistic black caricatures. So if that’s the case, then why wouldn’t Hollywood think that everyone all around the world wants to see white supremacist experiences on film? Couple that with the fact that historically, Hollywood has cast white actors in main roles and non-white actors in small, demeaning ones. With the deck stacked against them, non-white actors have hardly had a chance to show what kind of audience they could bring in until recent years.

What about the non-white families in No Escape?

No Escape could have featured any ex-pat family, but what’s more important is that the film could have shown a family who is native to the country. It’s not as if Wilson’s family is the only one trying to escape violence; there are plenty of families who have lived in the area their whole lives who are trying to survive. Why not focus on them?

The Guardian’s David Cox hit the nail on the head when critiquing The Impossible and the similar Clint Eastwood film Hereafter, stating they both concentrate “not on the plight of the indigenous victims but on the less harrowing experiences of privileged white visitors.” The New York Times’ A.O. Scott was equally scathing in his assessment of The Impossible’s whitewashed victimhood, writing that “[v]irtually everyone shown suffering after a tsunami is a European, Australian or American tourist, and the fact that the vast majority of the dead, injured and displaced were Asian never really registers.” Scott also pointed out how the generosity shown by the Thai doctors and village leaders to help the family “are treated like services to which wealthy Western travelers are entitled [and] the terrible effects of the tsunami on the local population are barely acknowledged.”

Using a locale as an exotic backdrop isn’t something that’s only seen in thrillers like No Escape. It’s also a big staple in rom-coms or “chick flicks” like Eat, Pray, Love (which uses India, Italy and Indonesia), Aloha (Hawaii) and Under the Tuscan Sun (Italy). In these films, the white (usually American) visitor is treated to the help and support of stereotypical characters from the region, usually resulting in an epiphany for the main character. Aloha is certainly one of the more recent films attempting to use this trope, only to fail exceedingly. Vue Weekly’s Brian Gibson described the film as offering “a taste of genuinely fraught and realistic native Hawaiian concerns, only to smushily sandwich them between thick slices of white people’s well-meaningness, hokeyness and lovelorn dilemmas.” Between the Allison Ng character and the general use of Hawaii in the film, Aloha was received so negatively that director Cameron Crowe felt compelled to issue an apology to all offended. Once again, Aloha turned out to be a case of denying real-world indigenous issues while exalting privileged ones.

Why this reflects on All Lives Matter

Let’s get back to why these films are like moving versions of the #AllLivesMatter hashtag. I am of the mindset that we are a lot more attuned to the perceptions the media puts out than we realize. When some people complain about racist issues in films, you might have heard people rebut with something like, “Why are you talking about the races of characters? Isn’t it just a movie? I don’t see a race issue since it’s just a movie.” Compare that to when people talk about #AllLivesMatter. When someone uses the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter or another hashtag focusing on the issues of a racial group, there will always be that person somewhere who will say something similar to, “Why are you talking about [insert minority] lives only? Aren’t all people affected by things every day? I don’t see a race issue since all lives matter.” Doesn’t that sound similar to you?

The American way to deal with race used to be to say, “I’m colorblind; I don’t see people’s race.” In reality, that’s a knee-jerk reaction to America’s problematic relationship with racial identity and racial politics. In an attempt to not repeat the crimes that led to the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, folks began to teach “colorblindness” with good intentions. However, “colorblindness” also became a covert way for many to keep inflicting racist attitudes. One such way is saying what Allen said when defending his casting choices –“I don’t see race, I just cast who’s best for the part.” Or, to bring it down to a more real-world scenario, that’s like how some employers say, “I don’t see race, I just hire who’s best for the job.”

It’s time we started seeing race, and not for racist reasons. We need to see race in an effort to realize that all lives actually do matter, no matter what your background is. We need to see race to respect other people’s backgrounds, cultures, and the unique issues they face. By ignoring race, we are removing ourselves from having a more complete view of each other and the world. We are essentially limiting our capacity for experiencing sympathy for others who are different from us.

The racist colorblindness that exists in movies, with white characters playing a majority of white and non-white characters, is just one aspect of how we keep ourselves ignorant. Buzzfeed recently published an article featuring its POC employees in recreations of posters of films that had all-white casts, like The Breakfast Club and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. As the article states, people of color make up over 40% of America’s population, yet only make up 16% of the movie roles. More than ever, Hollywood isn’t representing the masses and by not doing this, are stating that only some lives matter enough to be featured in films, that non-white lives only matter when they’re being shown in a historical context. The redundancy of Hollywood’s casting and deficiency in addressing non-white characters can be summed up in this repudiation of The Impossible’s trailer by Slate’s David Haglund: “The Impossible is, so far as one can tell from this trailer, about the uplifting story of five, well-off white people. Which is not to say that the lives of well-off white people don’t matter. But movies like this one create the unmistakable and morally repugnant impression that their lives matter more.”

This lack of compassion for other lives resonates with what’s going on in America today. By not respecting the lives of people of color, many police officers (and certain Neighborhood Watch members) do feel entitled to harass black, Latino and Native people on a daily basis. Middle Eastern Americans and Americans who practice Islam and Sikhism are routinely thought of as terrorists, when terrorism should not be reduced to wearing turbans or a single religion, especially when other religious fringe groups don’t get the same labeling (take for instance the Westboro Church, which inflicts psychological terrorism they believe spreads the word of Christ). Asian Americans are constantly afflicted with the “model minority” myth, a myth that is grounded in white supremacy and xenophobia. So much of our lives are based in ignorance and stereotype, and all of this is reflected in our moviemaking. Just think of what America might be like if we showcased the people who do make America great in our films. We might be less judgmental and more open to accepting the humanity existing in all of us.

Instead of blindly saying “All Lives Matter” or simply accepting the lie that “the best actor” got the part in a film, it’d behoove us to analyze just which lives seem to matter more in the media and in society. Starting there, America will really be able to create lasting change in how we see others and how we represent others in film.

Monique Jones is an entertainment blogger/journalist. She writes for Entertainment Weekly’s Community Blog, Black Girl Nerds, and Coming of Faith, and has written for Antenna Free TV, Racialicious, and many others. You can follow her on Twitter at @moniqueblognet and at her new Tumblr site, COLOR.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]