As the saying goes, “If you put 100 monkeys with typewriters in a room long enough, eventually you’ll get Hamlet.” But will you though? What are the actual odds of a monkey randomly replicating Hamlet. Let’s use reason and my C+ in college statistics to figure this out.

First, we’re going to set down some ground rules to limit our variables. What counts as Hamlet? Does capitalization matter? Does spacing? Are we factoring in proper formatting? What about punctuation? I asked my fellow Geekosystem writers and our friends at The Mary Sue, and everyone gave me a different answer on what they would accept from a monkey that could truly be called Hamlet.

Personally, if a monkey handed me a stack of papers with the words of Hamlet in one long unbroken string of all lowercase letters, I’d call it a success. Not all my colleagues were as lenient and would accept an identical copy. For the sake of this problem, we’re defining a successful Monkey Hamlet as being a character-for-character match to the text of the play we pulled off of MIT’s Shakespeare site, but formatting and capitalization don’t matter.

For our purposes,

alas, poor yorick!

is the same as

Alas, poor Yorick!

but

alaspooryorick

doesn’t cut it.

The number of characters being used is important so that we match the number of characters from the Hamlet text from MIT. Eliminating capitalization greatly improves the odds for the monkeys by limiting the number of possible characters typed. Punctuation and spacing will count so we can accurately match the total number of characters in the text, as well as the number of unique characters used.

There are 169,541 characters in the text according to the tool at www.wordcounter.net. That includes all 26 letters of the alphabet, spaces, periods, commas, apostrophes, question marks, exclamation points, colons, semicolons, ampersands, and hyphens. Altogether, that’s 36 possible characters.

We’ll increase the monkeys’ chances here and assume that they’re using special monkey typewriters with only the 36 keys they need to type. That’s one key per character, so they don’t have to worry about a shift key.

Each time a monkey presses a random key, they have a 1 in 36 chance of hitting the right one. The odds of them hitting the right sequence of characters decrease exponentially with each additional character. Just typing the name H-A-M-L-E-T with these parameters is highly unlikely, since each letter of the name only has a 1 in 36 chance of being typed correctly. So that’s:

36 x 36 x 36 x 36 x 36 x 36 or 366, which works out to 1 in 2,176,782,336. Since we’re working with 100 monkeys, that gives them slightly better odds as a group with 1 in 21,767,823, but it’s still not likely. And again, that’s on our special monkey typewriter. The odds would be much worse on a regular typewriter with more keys and variables like the shift key and caps lock.

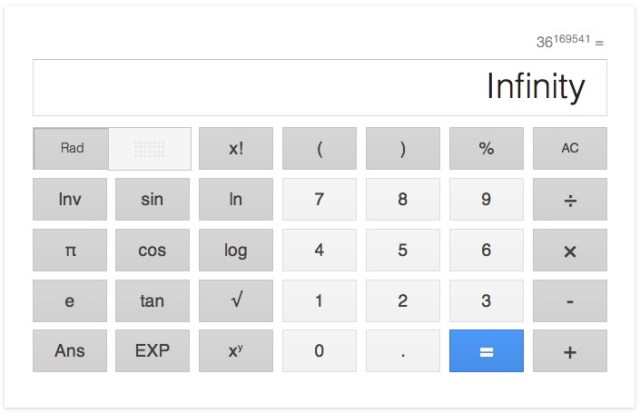

The odds of monkeys randomly typing out 169,541 correct characters in a row are 1 in 36169,541 which, if you type into Google’s calculator, gives you the following result:

Seriously. That’s the answer we got. The chances of monkeys typing Hamlet are one in infinity. Unless someone wants to multiply out 36169,541, that’s good enough for us.

There are, of course, variations on the saying. We’ve heard “A million monkeys with a million typewriters” or even “infinite monkeys with infinite typewriters.” “Infinite monkeys” is clearly not going to happen, and we doubt anyone is going to get a million of them together in a room, either. 100 is much more manageable. We’ve also heard variations of the phrase claiming the monkeys would write the complete works of Shakespeare, but come on. They can’t even get out Hamlet.

Of course, this saying has probably been around long before computers. With the addition of a little more technology than just a typewriter, the possibility of monkeys typing Hamlet could be greatly increased. Say all 100 of our special monkey typewriters were actually monkey computers with the same 36 keys, but networked together. Then we could check the input of each monkey button push against the actual text file of Hamlet.

If the button pushed corresponds to the next character in the text it is logged and put into a separate file, monkeyhamlet.txt. Only correct input is recorded in monkeyhamlet.txt, rather than any random button push. The program could be simultaneously comparing input from all 100 monkeys, and eventually, through sheer randomness on the part of the monkey, and sheer calculating exactitude on the part of the computer, monkeyhamlet.txt would be Hamlet.

Without the computer, if you just have monkeys typing away, you’re never going to get Hamlet, so maybe we can go ahead and let this phrase die off. Or at least update it a little.

(via Hamlet, Wordcounter.net, image via Oliver Hammond)

- How much is Monopoly money actually worth?

- What are the odds of filling out a perfect NCAA bracket?

- Should Scrabble change the point values of its tiles?

Published: Apr 28, 2014 02:42 pm