Molly Danger, a pet project of Jamal Igle that raised over $50,000 on kickstarter last year, was not in the least what I expected. Billed as an all-ages superhero comic starring a 10 year old girl, I dove into it expecting a cartoonish style, a light, perhaps even flippant tone, and in general just a book about a ten year old girl having a great time with her super-powers. While I expected the sort of breathless enthusiasm I get from My Little Pony or Adventure Time comics, what I got was a lot more serious, a lot darker (but not into “is this really for kids” darker, and as someone who was reading Anne Rice vampire novels at age 10, isn’t about to let dark or mature stop a child from reading anything she wants to). And when I say dark, by the way, I don’t mean gritty mcgrimdark, the tone of much of 90s superhero comics and a tendency even today (cough cough man of steel cough dark knight cough cough) to make things so grimly serious that, observed from outside the medium, it flips right back around to absurd. No, the darkness here is an undercurrent, a tone heard not in the actual dialogue or seen on the pages, but something inferred between the lines.

For me, the central question behind Molly Danger is, who are the real villains here? More thoughts after the jump, but for the TL;DR crowd or those avoiding spoilers: it’s a solidly good book. It didn’t blow my mind, as such, and while it wasn’t quite as colorful as I’d imagined it would be, it had a generous amount of depth and total lack of pandering to its all-ages audience. If you’re looking for a well-written story and a spectacular grasp of good narrative, I heartily recommend grabbing the the first issue on comixology, and keeping up with it until the end of the first trade.

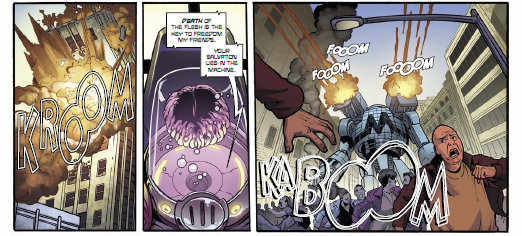

When I said the story has a spectacular grasp of good narrative, I wasn’t exaggerating. Not only are the panels and shots arranged to pull you along in the story without ham-fisted disruptions by lengthy box-text or exposition, the book starts out by diving right into a grandiose action scene, one which showcases the fine and sophisticated art, the beautiful lettering, the great color choices and themes, as well as introducing us to our titular hero, Molly Danger.

I was actually a bit soured by this page, and it was my first disappointment in the book. I looked at this and was a little jarred by the fact that Molly does not look like a ten year old to me. In the body, sure, but her face looked like she’s in her twenties; maybe it’s the groomed eyebrows, or the eyes heavy with eyeliner and makeup and mascara, or the mouth with the perfect rows of teeth in that sort of vacant magazine-model smile. Those opening pages immersed me wholly in the fight, in the setting, in how very well the colors were used and the angles and the art and the exposition-subtly-disguised-as-natural-dialogue, and suddenly I was completely put off.

But after reading through the rest of the book, I think it’s the right choice. What I was given was the idea of a ten-year-old hero without context, and after finishing the book and looking back, I think I should have been put off by this page. I don’t know if it was a conscious decision on the part of the creators, or just an accident of sometimes-comic-book-art-looks-that-way, but given all the other things we learn about Molly Danger and the world around her, the fact that she doesn’t look ten years old in this spread went from something confusing and weird to being a feature for me.

For you see, dear readers, there’s quite a lot that’s rotten in the state of Denmark. Starting with Molly, who isn’t a ten year old girl at all but an alien with origins not dissimilar from that of Superman, and an attitude not too far off from his as well (I mean the boy-scout sweet jocular Superman, by the by, and not any of his gritty mcgrimdark iterations). She does the right thing because it’s the right thing to do, but she doesn’t assume a bellicose ideology of good and evil, instead relying on her secure sense of right and wrong. That’s a big difference for me, and allows for a lot of character depth not just from the heroes but from the villains as well. Good and evil paints a world that can be neatly divided into black and white, a world where the inherent nature of a creature defines it for everyone else, whereas a sense of right and wrong is up to personal choices and ideas, both of which can mature and change throughout a series, the seedlings of which I’m seeing planted here.

Which brings me back around to the question I was (happily) left with at the end of the book: who are the villains, really? Molly works for an organization called D.A.R.T. (Danger’s Action Response Team) who, in a world defined by good and evil, would unequivocally be the good guys. Here, though, they may be the driving support behind Molly’s superheroics, but their motives are questionable and their sympathies strangely lacking. They treat Molly like a weapon that could go off at any time, and given some of Molly’s idiosyncrasies, I’m not sure they’re wrong to do so. Molly seems to waver in personality between the mature 30 year old person she is and the 10 year old girl she looks like, and that coupled with super-strength makes for a potentially terrifying combination.

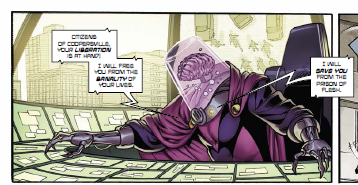

Then you have the super-villains, or “supermechs” as the book refers to them. People who have used bio-technology to improve themselves, to become super-fast or super-strong or super-brainy (as the first supermech we see is a literal floating brain with a robot body). The book implies they were average humans who have subjected themselves to extreme forms of body modification until they became these…well, sort of ubermensch, which supermech may be a nod to.

And of course we also have an antagonistic police force, one that appears none-too-happy with what amounts to a vigilante organization in the form of D.A.R.T, a mayor that is more concerned with the destruction of his city than with the lives saved by stopping the supermechs.

But are any of these, including Molly, really the villain of the series? While these forces certainly act in opposition to each other, none of them come across as the supreme antagonistic force. Even the supermechs, while clearly Molly’s foe of choice, in the end become sympathetic figures with implications of mind control by some shadowy figure they only refer to as “the father”.

In the end, I think the book isn’t about fighting the big fight at all, that these fights and struggles serve far more as the backdrop for a story that’s ultimately about the relationships we have and the bonds that we form, a subject infinitely more complicated than answering the question of who should win in a fight of good vs evil. And the book does this well! Relationships are messy and complicated and I wholeheartedly appreciated that the book didn’t oversimplify any of that, that it didn’t pull its punches when exploring the loneliness of a 30 year old alien in a ten year old’s body, or the restrictions felt by an organization that attempts to be a parent to Molly but largely comes across as a containment unit for Molly, or the motivations behind why someone would use bio-technology to advance their skills so far that they aren’t even recognizable as human anymore.

Ultimately that’s what I feel the book is getting at: what’s it really mean to be human, and to be a human girl, at that? Issues with identity are ones that we struggle with from the time we hit grade school until …well, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t have questions about who they really are, to be honest, and that’s exactly what puts this book squarely in the all-ages category for me. Rather than being something cute and sweet that we can all enjoy because we all remember being young, it’s a much more serious take on experiences we all share, at all ages of life.

What about you? Did you back the Kickstarter? Was it everything you wanted and more? Let us know in the comments!

Molly Danger is written and penciled by Jamal Igle, inked by Juan Castro, colored by Romulo Fajardo, and lettered by Frank Cvetkovic. You can pick up issue #1 on Comixology.

Published: Aug 9, 2013 01:57 pm