Masaki Kamakura, a biotechnology researcher in Japan, has identified the protein in royal jelly that turns female worker bees into queen bees, which are larger in size, more fertile, and live longer. So, like anyone else would do upon making this discovery, he tried to turn a regular fly into a queen fly. And it totally worked. It’s a huge discovery in the study of insects:

“Finding the active components of royal jelly that are important for queen development has been kind of a holy grail of insect research for decades,” says Gro Admam, an entomologist at Arizona State University in Tempe, who was not involved in the new paper.

Does this mean there is a formula coming for humans? Is this a good time for a Superfly joke?

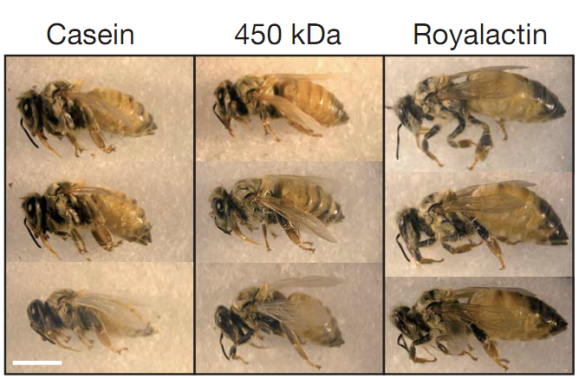

In an article published this week in Nature, Kamakura explains how, after isolating royalactin, he fed a similar compound to fruitflies while they were still in their larval stage. Previously, he’d fed two bees with identical DNA the compound, and they both became queens. So he figured that a similar insect would react the same way, and since the genetics of fruitflies have been studied extensively, it would be easy to isolate the genes that reacted to royalactin.

And so, the “superflies” grew up.

In a typical bee community, the “royals” will continue eating royal jelly while the workers switch to a different diet and remain workers while the queens become superbees, creating a “caste” system among the bees.

All newly hatched honeybee larvae gorge on the heady mix of proteins, fats, sugars and vitamins. After three days, though, soon-to-be worker bees switch to a diet of honey, pollen and water, while the heirs to throne continue to eat royal jelly. This shift underpins the eusocial lifestyle of honeybees, in which sterile workers support a hyper-fertile queen, who grows much larger and lives about 20 times longer than workers.

Maybe this is the worker bees’ chance to “stick it to the man.”

This experiment was the first time royal jelly had been fed to another insect to create queen “non-bees.” Entomologists are hoping to further discover how royalactin works and apply it to studies on the division of labor and social behavior in beehives.

However, despite what you might be reading on the Internet, there is no such application for humans. So this will not be happening any time soon:

(The Great Beyond via io9)

Published: Apr 25, 2011 04:45 pm