Here’s One For the Arachnophiles: Scientist Has a Vast Collection of Spider Porn Online (For Science)

she blinded me with science

When you woke up this morning, you may have thought to yourself, “My goodness! I sure hope someone is documenting spider genitalia online in order to better identify more species of spiders, what with there being 42,473 of them!” Well, you are in luck! Dr. Nina Sandlin has taken on the perverted yet ultimately beneficial task of cataloging the genitals of nearly 200 different species of spiders, specifically, female spiders, in order to identify which species of spider they are. Want to know how weird it is? Come inside! All the spider genitalia you’ve ever wanted to see after the jump!

Besides this just being super interesting all by itself, Dr. Sandlin has taken on a task that can only be described as “it’s a dirty job, but someone has to do it.” Here is how this started: the Linyphiidae family of spiders is the second largest family of spiders out of all the over 42,000 species of spider. Referred to as “sheet-weavers,” linyphiidae are not well-researched because of their teeny tiny sizes. (They range from 2 to 7 mm in length, some even smaller than 2 mm.) The smallest of this small species are in the Erigoninae subfamily, and are so small that only the males, who have more distinguishing physical features, are easily identifiable. The females are more homogenous — brown and featureless.

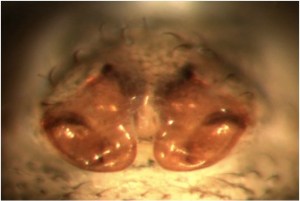

And it was at that point when Dr. Sandlin thought to look at their genitals. And here is a fun fact about the male erigonines: the organs that insert sperm into a female are located in “fist-like” structures that are attached to their faces. They can be seen in the top pic. All females have for scientists to look at is their epigyna, “a small, hardened, shield-like plate on the ventral side of the abdomen, usually just covering the two openings to the spermathecae: her internal sperm-collecting pouches.” And here is a creepy fact about the erigonines:

It has been said that rich collections of these spiders are hidden in museum collections, floating in jars labeled only “Undetermined.”

But after painstakingly precise and sterile procedures and photography techniques, Dr. Sandlin has created a catalog of the epygyna of female erigonines that did not exist before, and here’s the best part! You can totally look at it online! LinEpig is a gallery (on Picasa) of identified erigonines. Or, if you’re not a scientist, it’s a gallery of sexy, sexy spider vadge.

But after painstakingly precise and sterile procedures and photography techniques, Dr. Sandlin has created a catalog of the epygyna of female erigonines that did not exist before, and here’s the best part! You can totally look at it online! LinEpig is a gallery (on Picasa) of identified erigonines. Or, if you’re not a scientist, it’s a gallery of sexy, sexy spider vadge.

Seriously though, what is interesting and important about this — and why Dr. Sandlin spends her Mondays in a dark room, away from her colleagues — is that 1. the epigyna of erigonines are smaller than a speck of dirt, and photographing them is a process all by itself, let alone trying to find any distinguishing features:

If you’ve ever tried to frame a photograph, you know that every time you think you’ve cleaned the glass to perfection, all the universe’s dust suddenly flies towards it. That’s what it’s like with spider genitalia photographs, too.

And:

The particles of fine sand or electrophoresis beads Nina uses to position specimens often float above the spiders in a cloud, bury them completely, or reflect light from the two very bright bulbs that shine on the watch glass, creating glare that can ruin a good image.

And 2. Because of Dr. Sandlin’s efforts, more of these mostly ignored spiders are getting the research they’ve been lacking. Other spider researchers are starting to send her specimens to identify, signaling a growing interest in arachnological studies. Dr. Sandlin is also soliciting museums and other researchers to send her specimens to identify.

Next step: Getting spiders to sign release forms.

(Scientific American via Mental Floss)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]