The trouble with supersonic travel is multifaceted: There’s the cost, the sound, the efficiency, and the sound — did we mention the sound? Sonic booms are, not surprisingly, incredibly loud, and what you may not know (I didn’t) is that aircraft traveling at such speeds are making that noise the entire time they’re flying. Perhaps it’s not surprising that supersonic flight has been banned over land, out of concern for people’s wellbeing and worry over the sound damaging local wildlife. However, when it comes to reducing sonic booms, two wings are better than one.

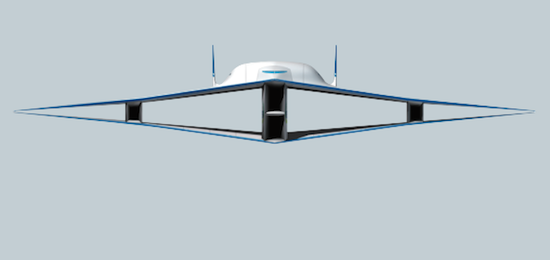

That groan-inducing paragraph hook is all about biplanes, which were first theorized to reduce sonic booms all the way back in the 1950s by Adolf Busemann. Like other German engineers after the fall of Nazi Germany, Busemann came to the U.S. where he worked on advanced airplane design, including his theories about supersonic biplanes. He figured that two wings could cancel out the double-headed problem of sonic booms, conclusions that have been confirmed by research teams at MIT and Tohoku University.

Sonic booms are created when an aircraft approaches the speed of sound. When it does, the force of the aircraft moving forward creates an enormous pressure wave in front of the aircraft. Meanwhile, a second pressure wave is created behind the aircraft as the surrounding air rushes in to fill the void left in the craft’s wake. The two come together to create the familiar, continuous, ear-shattering bang called a sonic rain boom.

Busemann’s work suggested that two wings would allow air to pass between them and cancel out the sonic boom. His design had a fatal flaw, however: At subsonic speeds it created no lift, and would not fly.

Enter the MIT team, which not only prove Busemann’s original theory with computer simulation but improved upon it allowing it to function at subsonic speeds. What’s more, they believe their design also improves the craft’s overall efficiency being much lighter and requiring less fuel. From MIT news:

They found that smoothing out the inner surface of each wing slightly created a wider channel through which air could flow. The researchers also found that by bumping out the top edge of the higher wing, and the bottom edge of the lower wing, the conceptual plane was able to fly at supersonic speeds, with half the drag of conventional supersonic jets such as the Concorde. Wang says this kind of performance could potentially cut the amount of fuel required to fly the plane by more than half.

While both MIT and Tokoku University are continuing work on their supersonic biplane designs, it’s unlikely that these super quiet supersonic planes will be gracing the air anytime soon. However, with the Concorde long retired, the area of supersonic commuter air travel is just itching for a comeback.

(MIT, Gizmag, via Slashdot image via Tohoku University)

Published: Mar 19, 2012 06:08 pm