The Psychology of Fandom: Why We Get Attached to Fictional Characters

When I set out to research Fangirls, I was already well acquainted with the art of fangirling.

Having been a venerable X-Files fangirl throughout my teen years, the concepts of “OTPs”, “UST” and fanfiction weren’t new to me in the least. What proved to be different, approaching fandom as an adult woman, was the depth of human emotion that I became aware of. Whereas my preteen flailings were far more about exploring human nature, my adult efforts to connect with a fandom were far more about understanding why I fangirl. Why do any of us? Why do we respond to fictional characters, whether they dwell in the pages of a well-loved book or on one of our many screens, as though they were real people? The short answer is empathy.

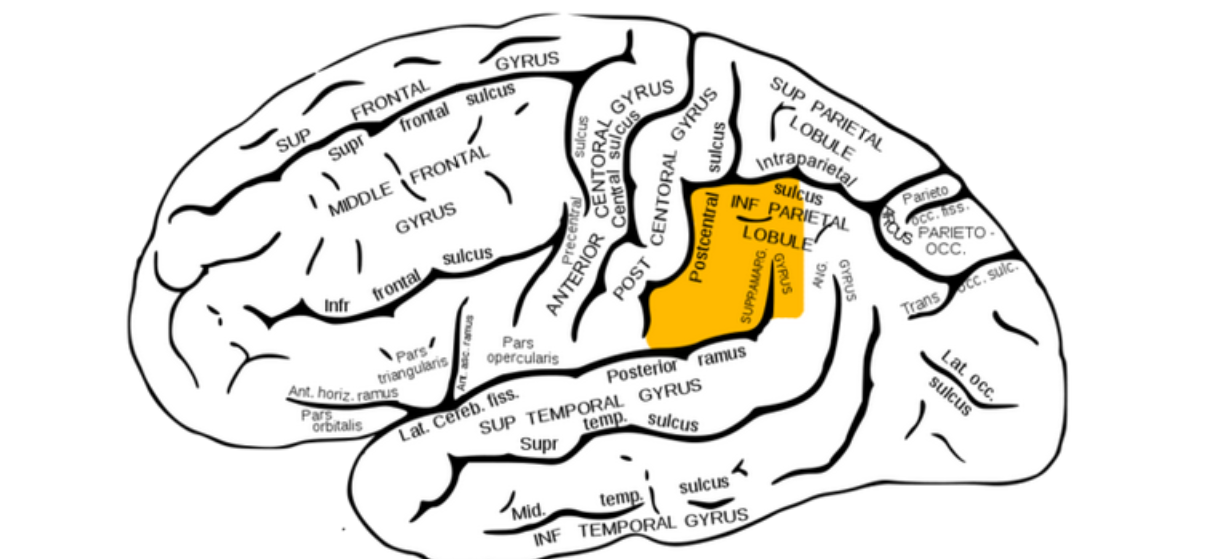

In our brains, empathy lives in a little lobe called the right supramarginal gyrus. When we interact with other humans, we use ourselves as something of an emotional yardstick to try to figure out how they’re feeling. We read their body language, tone of voice, facial expressions and use our own internal experience as a gauge to guide our interactions with them. What’s interesting is that in studies where this part of the brain was disrupted, participants reported finding it increasingly difficult to not project their own emotional states onto others. This, of course, is something that we all do to some degree, particularly if we’re stressed or trying to make decisions more quickly than our gyrus can handle.

Now, when we empathize with someone who is physically in front of us, we have the potential for a tactile experience — hugging them, squeezing their hand reassuringly — that bolsters our emotional response. On some level, empathy is a conscious process — and there are ways to improve our ability to empathize with others. But at a neurobiological level, there are certain functions that either exist or don’t in each one of us. Sociopaths, presumably, have a lower functioning gyrus. Empaths, on the other hand, have a higher functioning one.

One thing that helps us empathize with family and friends, no matter what our baseline capabilities to do so are, is trying to fill in the details of what we don’t know about their situation. Interestingly enough, this is also more or less what we do with fictional characters; in fact, it’s sometimes easier to empathize with them because we are often given, expositionally, far more detailed and intimate knowledge of a character than we would ever know about someone in our real lives. And, as in life, it’s our nature to fill in the blanks when we’re presented with a character that we haven’t gotten to know very well yet. Fanfiction is one way that we do this on a community level. Headcanons, a term in fandom that refers to what an individual believes to be true about a character, even though it’s not “canon”, are another way that we flesh out the details of these character’s lives as we attempt to understand and, ultimately, feel for them on some level.

On a neurobiological level, our experience of consuming fiction is actually very real. Measurably so. When we read about the scent of coffee, for instance, the olfactory center of our brain lights up. We can’t really smell it, but we’re familiar with the scent and we can conjure it up. Especially if the language is rich and helps us recreate the experience. Metaphors can be helpful in giving us a vibrant, multi-sensory experience when we’re reading, similes help a wider range of readers experience the same emotion, based on our own internal experiences.

Rather than try to locate the precise ontological identities of characters, I would like to look instead at the way we come to know characters, which, I hope to show, is not so unlike the way we come to know people, in person and particularly through works of non-fiction.

— Howard Sklar, Believable Fictions

The biggest philosophical dilemma we face is defining what it means to be real. On a somewhat basal level, “we” are real and fictional characters are “unreal”; at most they are representations or amalgams of real people, but they themselves do not possess any actual solitary identity in life. They are not flesh and blood. We cannot engage with them on that touchable level we could with, say, a friend who we are comforting. In film and television, we can often extend our feelings for characters to the actors who portray them which is innocuous at best but potentially quite unnerving for the actors at worst. Still, trying to define a character’s relative “realness” is often a testament to how they’re written and how they’re played by the actor.

Literary theorists struggle to accept that a character can be real, because taken out of the context of their universe (whether in book, television or film) they aren’t able to stand up on their own. Of course, one could argue that there are some literary characters who are so timeless, so placeless, that this argument would be rendered invalid. Books and film have often taken a stab at their own high-budget versions of fanfiction, taking well-loved characters (that are likely in the public domain) and plopping them into alternate universes. Think Once Upon a Time.

Whether or not characters are ontologically “real”, our familiarity with them renders them very emotionally potent; a kind of emotional truth that we experience at a biochemical level quite the same as we would with strangers whom we get to know over the course of a season — or years, for the loyalist of fans.

Our interpretation of the actors that portray the characters, or even the writer who penned them, may not always be that misguided. Actors are often typecast. Writers often insert elements of their own personality into a character or two, even subconsciously. Our relationship to the characters, then, does stem from relating to the actor humans who bring them to life in our imagination. It’s all based on real emotions. Real experiences.

Some philosophers have proposed that the emotional response we have to fictional characters can’t be real because it’s not directed at real people. It’s “irrational, incoherent, and inconsistent” to think we can direct real emotions at unreal objects, argues Colin Radford.

To further elaborate, he asks us to consider how our emotional response to a horrible event would change if we later found out it was false. While we believe it to be true, we respond empathetically — however, if we believe an account to be false, or if we know it to be, we cannot rationally empathize. When we read a book or watch a film, however, we are knowingly partaking in something false, yet somehow are still greatly moved by it.

Another philosopher, Kendall Walton, wonders if what we experience watching a horror movie, for example, is not real fear — but quasi-fear. These almost-but-not-quite-emotions are not based on belief, but make-belief. Children playing a game of make-believe with their father, in which he pretends to be a monster chasing them, will playfully run and hide from him but not hesitate to run back to him when the game is over. These quasi-emotions account for our enjoyment of being spooked during a scary movie, or our desire to have a good cry watching something like Steel Magnolias for the umpteenth time. Further, it’s not as though just any movie or book can give us those fun (or awful) heebie jeebies or make you cry big man-tears.

While we may choose, however, to engage with fiction we do not appear to be in control of our emotional responses to it — quasi or not. And even still, how is it then that we can go full-well into a movie, or pick up a book we’ve read a million times, not only knowing the emotional climax is coming but knowing full well it’s not “real” — yet we still find ourselves tearing up? Oh, what a tangled web we weave.

We would do well to remember why we read or watch films in the first place; isn’t it to experience that which we have not experienced in our real lives? Understand other people’s lives, inner and external? Isn’t a mark of good characterization how “real” they feel to us?

We’ve all heard anecdotes about actors who play medical professionals on television finding themselves in situations where actual medical care needs to be rendered — and they have to remind those around them that they are not, in fact, a doctor. They just play one on TV.

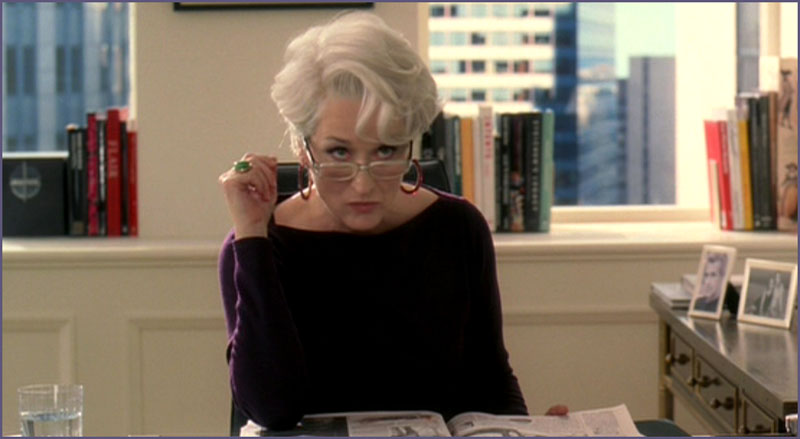

It’s the purpose of the creators of such characters that we suspend our belief in order to see the actor as the character; we look at the skill of artists like Meryl Streep who seamlessly become the character, where we don’t have to put much effort in at all to convince ourselves that it’s Miranda Priestly and not just Meryl Streep with a great haircut. But how do we “decide” on an unconscious level that it’s not Meryl Streep on our TV?

Philosopher Tamar Gendler posits that we have two competing levels of consciousness — belief and alief. The former being what governs our intellectual knowledge that yes, fiction is not fact. Where the latter, what she calls “alief” is our brain’s ability to suspend our belief that fiction is not “real” — which is what makes watching movies enjoyable. We can get “lost” in them, but as soon as the credits roll and we return to our day to day life, we know it was just Meryl Streep with a superb haircut.

This system of alief, however, is a process that becomes increasingly more well developed as we grow up. This is why children are even more enraptured by stories than we are. If you’ve ever taken a young child to a live theatre performance, you’re probably familiar with the struggle of having to explain to them that the actor playing the character was only pretending to be hurt.

Psychologists have also been interested in what they call “experience-taking”, wherein we subconsciously take on traits, attitudes and behaviors of our favorite characters. Our faves (problematic or no) are often such because we strongly identify with them. In one study, psychologists found that participants had a much harder time “experience-taking” when they were reading in front of a mirror; presumably because they were constantly reminded of their own self-concept. Thus, “experience-taking” can only happen when an individual can suppress their own identity and “lose themselves” in the book or the film.

“Experience-taking” is different from putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, which is more “perspective-taking” —like when we were discussing empathy earlier. The act of taking on experience, traits or attributes is very powerful; since it happens on an unconscious level, over time positive change can develop for the individual: increased confidence, motivation and a greater level of comfort socially, for one.

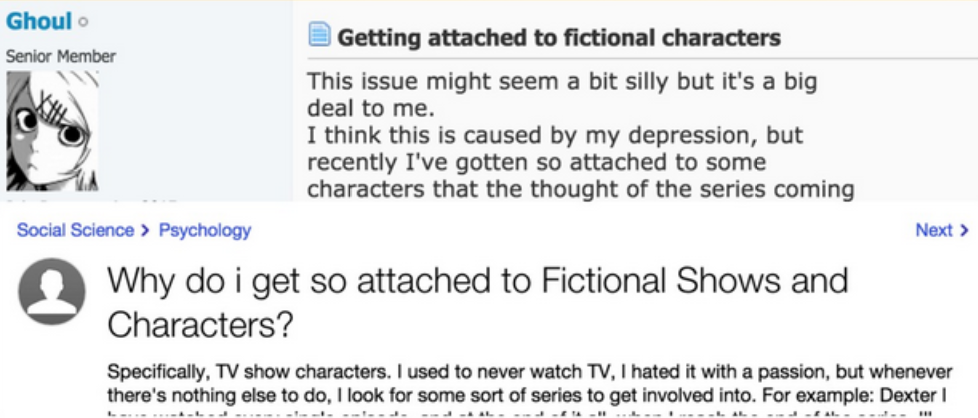

If you Google “why do we get attached to fictional characters?” 2,800,000 results are returned. Some of them are articles like this, asking questions about the psychology, the philosophy, of how we relate to our favorite characters. Others, however, are a slew of message board posts and blogs where people wonder rather frightfully if they are “sick” for developing very real emotional responses to characters that they know, intellectually, are not real.

What we look for when it comes to relating to characters isn’t necessarily the same as what we would admire about them. In fact, when it comes to really distilling down to what makes us really, really, really love a character, it’s not so much that we think of them as our fictional counterpart, but that we’d like to be friends with them.

At the root, our attraction to fictional characters may not be that we identify with them that much at all — but rather, we just really enjoy spending time with them. Whether it be in the pages of a book, a new season of TV or a feature length film, for a few hours at least we’re lost in their world.

And maybe the mark of a truly memorable fictional character is how often we take them with us when we head back to reality.

Abby Norman is a journalist based in New England. Her work has appeared on The Huffington Post, Alternet, The Mary Sue, Bustle, All That is Interesting, Hopes & Fears, The Liberty Project and other online and print publications. She is a regular contributor to Human Parts on Medium. Stalk her more efficiently at www.notabbynormal.com or sign up for her weekly newsletter here.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]