The Top 5 Queer Voices in Anime and Manga

You should probably go watch and read all of these immediately.

Anime and manga hold a strange allure for teens. I was a total anime geek in high school, the kind that watched anime with friends at every hangout, stayed up late reading manga or sneakily catching bits of FLCL on Adult Swim, and attended anime conventions. Even with this history, I can’t quite put my finger on what drew us into the world of anime. Did we already feel like outcasts before we got sucked in? It feels less like coincidence and more like logic that many of the anime and manga lovers I knew as a teen (and have met since!) are also queer. Were we able to see ourselves more in those stories because they contained more queer characters than American TV?

These genres have a somewhat deceiving glamour when it comes to the hunt for queer representation. If you set out to make a list of LGBTQ characters in anime and manga, you might be surprised by the list’s length. Unfortunately, just like American comics and cartoons, these genres are rife with stereotypes. And, just like American comics and cartoons, the portrayals of transgender and genderqueer folks are usually nonexistent or offensive. A newbie anime geek might be surprised to find themselves still thirsting for realistic, believable queer people.

Don’t fret, friends! As I’ve become more critical about what I watch and read, I’ve come across anime and manga that do contain nuanced portrayals of queer, genderqueer and transgender characters. I’m delighted to share with you my top five anime and manga series that uplift queer voices, and hope that there will be many more to add to this list in the future.

#5: Azumanga Daioh

Azumanga Daioh is a slice-of-life series about the daily adventures of a group of teen girls. Each character has her own strange quirks: Sakaki is an accidental tsundere (a girl with a tough, even cold exterior who actually has a kinder, warmer side) who just wants cats to love her, Tomo is unpredictable and childish, Chiyo is a child genius, and Kasuga, AKA “Osaka,” is a super space cadet. And then, there is Kaori.

One of Kaori’s defining characteristics is that she has a crush on Sakaki. In manga, it’s not unusual for girls to have infatuations with tsundere characters. Late in the Fruit’s Basket manga, for example, Rika attracts some younger girls who find out she was in a gang. However, these crushes are usually insignificant and seem to be justified by the tsundere character’s tough, “masculine” qualities. (Sakaki is crushable because she is athletic, and thus “cooler than the boys.”) Kaori’s crush is a bit unique.

First, Kaori’s feelings are explicit from day one, and never waver. In the beginning of the series, she shows manga/anime telltale signs of a crush: she blushes during conversations, acts as her crush’s cheerleader during athletic contests or whenever possible, and is jealous when others are able to get close to Sakaki. (Through an odd series of events, a photo of Tomo sleeping and accidentally resting her hand on Sakaki’s boob surfaces. When Tomo nonchalantly shows Kaori the photo, Kaori flips her shit.) At the end of the series, it becomes clear that Kaori’s feelings have not dissipated. Despite being much shorter than Sakaki, she gets lucky and ends up tied to her for a three-legged race. At the end of the race, Kaori sits in a happy daze, hoping they’ll be stuck together forever. This crush is consistent, and it is real.

The real bummer about Kaori’s character (and the reason Azumanga Daioh is lowest on this list) is that she operates on the periphery of the main friend group. She isn’t able to visit Chiyo’s summer house until their senior year, and thus misses out on key bonding time that even includes the teachers. During their third and final year, she alone ends up in a different class and her scenes – which are few and far apart – are dominated by a need to run away from a creepy male teacher. It’s sad that the manga pushes its only queer character to the periphery, but in a way this adds realism to the story. Many queer youth are treated as outcasts during high school, so Kaori isn’t alone.

Her exclusion aside, Kaori’s crush feels very real and poignant. Love and romance do matter to the girls; various characters pine after not having boyfriends, and in a hilarious scene Kurosawa, the smokin’ hot gym teacher who you’ll wish was queer, accidentally gets drunk and tells raunchy stories about men she’s dated. This all serves to reinforce the significance of Kaori’s plotline: hers is the only romance in the entire manga. What’s more, it’s a realistic story about being in love with a (probably) straight girl.

#4: Wandering Son

I don’t want to dwell on Wandering Son, because Tash Wolfe gave a lovely review of it in her visual representation series, and you should seriously go read that! However, like Tash and many others, Wandering Son stands out to me as one of few manga to treat transgender identities as real and valid, rather than the butt of a joke.

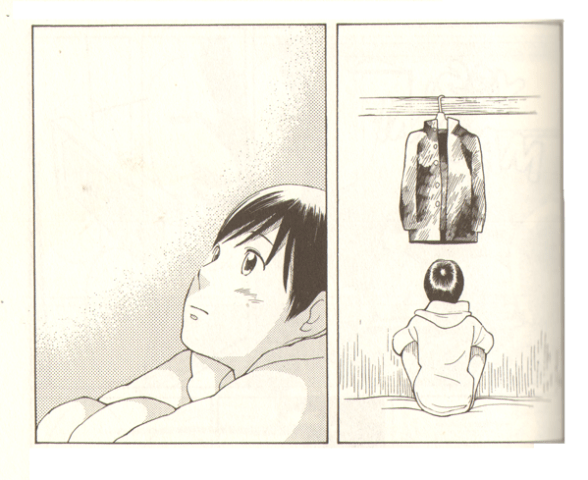

To get you up to speed: Wandering Son follows two fifth graders who do not identify with the genders they were assigned at birth. Shuichi Nitori identifies as a girl, and Yoshino Takatsuki identifies as a boy. I love this story not only because there are socially awkward middle schoolers (oh middle school, what a terrible time!) but also because it is well rounded. While it does show the positive things that the kids experience – for example, in addition to finding support and friendship in Yoshino, Shuichi comes out to a cis classmate and gains her as an ally – it doesn’t shy away from the negative realities. In the first volume, Yoshino is bullied because of his gender presentation. Similarly, we spend a good deal of time in Shuichi’s head, seeing her dreams and experiencing her anxieties and fears.

In addition to the realism of its characters, Wandering Son stands out as a series that puts Yoshino and Shuichi at the forefront of the story. Like Azumanga Daioh, many other anime and manga sideline their queer and transgender characters, as if they’re checking the diversity box and then going right back to focusing on cis, straight protagonists. While there are some solid anime that have queer protagonists (keep reading!) transgender protagonists are practically nonexistent. Wandering Son is a game changer, especially because it is such a well-crafted story. Hopefully mangaka (the people who make manga) take this as a signal that we need more realistic, well-written transgender characters.

#3: Cardcaptor Sakura

In my younger days, I would respond to conversations about Sailor Moon by giving everyone my spiel on why Cardcaptor Sakura is the greatest show ever. (I don’t mean to hate on Sailor Moon! I didn’t give it a chance in high school and missed out on the lesbians, so it’s all my bad.) Cardcaptor Sakura is a seventy-episode long anime about a ten-year-old girl who is heir to the great magician Clow Reed’s set of magical cards. The Clow Cards grant Sakura various powers. For example, when she captures the “jump” card she can leap tall buildings in a single bound! Suck it, Superman. However, when Sakura discovers the cards, she accidentally sets them free to wreak havoc around the city. With help from her guardian, a little talking stuffed animal named Kero, and from her friend Tomoyo, Sakura vows to get them back.

Aside from starring a young, female heroine – and thus already being badass – Cardcaptor is full of queer people! It’s difficult to fully discuss the gay characters without spoilers, but at the end of the series we learn that two guys are each other’s true love. What makes this moment even better is that Sakura unhesitatingly accepts and supports the gay couple. However, as a lady queer I’m super biased and care more about seeing lady queers. Plus, I can discuss this without giving away spoilers: Tomoyo is totally a lesbian.

OK, back up. First, I admit that I’m making a jump here. The series never confirms this, but that is a potential strength of Tomoyo’s storyline. While young kids often know that they are gay, queer, or transgender, it’s not uncommon for them to wait to come out until later in life due to safety reasons, because they don’t see a need to come out, or because they don’t have the terminology. Additionally, Cardcaptor is full of unrequited crushes and has canonically gay soul mates, so it isn’t far-fetched to claim that Tomoyo’s feelings for Sakura are romantic.

Tomoyo’s attitude toward Sakura also has that shoujo romance, my-feelings-for-you-will-only-grow kind of feel. (Shoujo = “girly” anime that is more about ~love love~ and less about ~fight fight~. I know, gross gender norms alert.) In anime, many crushes that become relationships start out as situations in which one character stays in the background and supports another character through some kind of trial. (Again, see Fruit’s Basket, in which Tohru spends all her time supporting Kyo and Yuki; Death Note, in which literally everything Misa does is to help Light; or, hell, even the Harry Potter films, when Ginny basically sits around being helpful while waiting for Harry to notice her.) Tomoyo is Sakura’s main support; while she dresses her up in cute clothing because she likes making Sakura look cute (gay feelings red alert) she also provides moral support and assistance whenever Sakura needs it. Tomoyo is always there for Sakura, even when being there puts her life in danger. Sometimes we give so much because we’re hoping for love in return.

The most significant proof of Tomoyo’s queerness comes at the end of the series. One of Cardcaptor’s final messages is that even if you can’t be with the one you love, seeing that person be happy can give you happiness. There is no character who embodies this message more than Tomoyo: she literally follows Sakura around, encouraging her, being her cheerleader, and helping her keep track of all the magic junk she’s gotta learn.

Like the other characters on this list, Tomoyo is interesting and complicated. She’s multi-talented and sings in addition to making clothing and amateur films, she’s intelligent, and she’s resilient. In a poignant episode, Tomoyo loses her voice and cannot speak or sing until Sakura captures the next Clow Card. However, she remains strong throughout this tragedy, and comforts the distraught Sakura because she trusts Sakura so deeply that she feels no fear.

I am shamelessly claiming the amazing Tomoyo for team queer! May she love Sakura forever.

#2: Tokyo Godfathers

Psych! Tokyo Godfathers is not a series, it is a movie by Satoshi Kon, creator of the show Paranoia Agent along with a slew of genius animated films. The plot follows three homeless people in Tokyo who, on Christmas Eve, find a baby in a pile of trash, and resolve to return it to it’s mother. Also, the reason it’s so funny that I lied to you a little is that Tokyo Godfathers is about liars. (It’s also about family. Cue laughter!)

Our three protagonists in the film are Gin, a cruel, alcoholic old man; Miyuki, a teen girl who is more caring than she lets on; and Hana, an older trans woman with a big heart and a flair for drama. When the film begins, Gin and Hana stand in the audience at a Christmas nativity play/sermon. While Gin sleeps through the event, wanting only to get food at the end, Hana is rapt. The contrasts between the two grow almost as soon as Gin wakes up: Hana believes in God, Gin does not. (God, however, is flawed: Hana explains that He made a mistake when He did not cause her to be born a woman. Of course, Hana loves others despite their flaws.) Hana thinks of others – she makes sure they get food for Miyuki, who is hiding up on a roof – while Gin thinks only of getting alcohol. As the movie goes on, it becomes clear that Gin is a liar. Hana, of course, is a truth-teller.

From a moral viewpoint, it doesn’t matter that Hana has no penchant for lies. Most of the characters – major and minor – are liars, and that does not make them any less likable. However, in the larger context of anime, this is a pretty big deal. Anime has this really terrible trope called “man in a dress,” which is what it sounds like. However, as Tokyo Godfather’s plot progresses all lies are revealed, and Hana is never “exposed” because there is nothing to expose. Satoshi Kon even subverts the “man in a dress” trope by providing a real man in a dress: an assassin who dresses as a woman to get into a wedding party and kill the groom. Like all the liars in Tokyo Godfathers, the assassin’s deceit is revealed when he strips off his wig during his escape. The assassin is a man in a dress. Hana is a woman.

Among the many reasons to love Hana is that her story does not dwell offensively on her transition. Considering that most stories containing transgender people seem to think it’s absolutely necessary to show the trans women characters dressed as men, this is pretty significant. Second, Hana is hilarious and incredibly fun. She can jump from melancholy to angry to ferociously maternal in the flash of an eye, and keeps everyone on their toes. Her energy comes to feel like it’s driving the plot; when other characters have stopped to reflect or rest, Hana is often literally running toward the next plot point while dragging others with her.

A wonderful piece of Hana’s storyline (which is too spoilery to analyze much) is that it asserts the validity and importance of chosen family. Throughout the film we are given a back-story on each protagonist, and these stories are ultimately about family and forgiveness. Hana’s back-story is no different, which is lovely.

#1: Ouran High School Host Club

I know I just talked up Cardcaptor Sakura, but Ouran High School Host Club blows everyone out of the water. It parodies anime’s gay and gender stereotypes and provides nuanced portrayals of queer and genderqueer characters, all while having a mountain of fun.

The plot is pretty ridiculous: our protagonist, Haruhi Fujioka, is a high school freshman attending the prestigious Ouran Academy on scholarship. While hunting for a quiet place to study, Haruhi stumbles upon Ouran’s Host Club: an after-school club run by handsome boys who play romantic hosts to the girls of the school. (A quick explanatory note: in Japan, there are real host and hostess clubs. Male hosts get the women drinks, talk or provide a listening ear, and flirt to earn money.) Upon meeting these weirdos, Haruhi immediately wants to leave, but fatefully breaks an incredibly expensive vase. Unsurprisingly, she becomes a host in order to repay her debt. Spoiler alert: the club thinks she’s a boy at first, but her ID states that she’s a girl. Drama!!

This kind of gender confusion isn’t uncommon in anime. More feminine-looking boys are often mistaken for girls, and more androgynous-looking girls vice versa. Some series even rely on gender confusion as plot points, but usually not in a positive way (again, see Tash’s article.) Ouran, however, subverts this trope pretty quickly. In the first episode, Haruhi explains that she has a “low perception” of gender. She is happiest in neutral clothing, and when a kid gets gum in her hair she chops it to pixie length without a second thought. The host club boys are often cooking up schemes to get her into dresses and bikinis. When these schemes succeed, Haruhi either has no reaction to the clothing or treats the high heels and frills more as costume than expression of identity. In the Ouran sequel that only exists in my head, Haruhi identifies as agender and uses they/them pronouns.

Haruhi isn’t the only Ouran character with a complicated gender identity. Her father Ryoji works as a drag queen and asks to be called by his stage name, “Ranka.” After his wife passed away, he grew out his hair and began dressing more feminine outside of work, claiming he felt a need to fill the role of father and mother for Haruhi. He identifies as bisexual and seems to have been fully open about his identity with his wife. In fact, the show suggests Kotoko was also bisexual when it reveals that she was fanatic for a girl’s performance art club known for being really gay!

In terms of sexuality, Haruhi’s father isn’t the sole queer character present. Again, I won’t spoil it, but in the anime two of the host club men are hinted to have romantic feelings for each other. (There is an Ouran manga in which these two are straight, however the manga is far inferior to the fabulous anime.) Additionally, the Host Club has a rival club from an all girls’ school called Lobelia, and the club members name same-sex romantic relationships as one of the draws of their school. Haruhi’s own sexuality is left ambiguous, but her comfort with being fawned over by the host club fangirls suggests that she many not be straight.

Ouran stands out not only because it’s a hilarious, fun series that plays with gender and defies stereotypes, but also because the straight-to-queer ratio is 50-50. It’s a complete anime with (unfortunately) only twenty-six episodes, so I recommend that you start binge-watching it on Netflix right now.

Alenka Figa is a queer, feminist wannabe-educator who is over traditional education. She spends her days reading comics at her toy store day job, watching Adventure Time, and writing book and comic reviews at her Tumblr blog League of Shadows.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com