The Washington Post’s Top Secret America: What Does It All Mean?

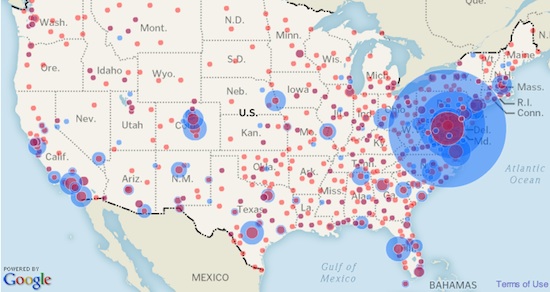

For nearly two years, The Washington Post has been working on a massive investigative piece on the state of the post-9/11 intelligence and security industries which would have been impossible before the Internet. Titled “Top Secret America,” the Post‘s exposé required the labors of more than 20 journalists. The report’s key takeaways may not be terrible surprises with respect to the conventional wisdom about the military-industrial complex — that it wastes money and is so disorganized that key pieces of intelligence get ignored to potentially perilous effect — but its thoroughness and searchability make it a uniquely 21st century piece of reporting, both for its subject matter and for its own composition.

Here’s the heart of the report on the 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies involved in America’s counterterror, homeland security, and intelligence operations, as summarized by veteran investigative journalists Dana Priest and William M. Arkin:

* Many security and intelligence agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste. For example, 51 federal organizations and military commands, operating in 15 U.S. cities, track the flow of money to and from terrorist networks.

* Analysts who make sense of documents and conversations obtained by foreign and domestic spying share their judgment by publishing 50,000 intelligence reports each year – a volume so large that many are routinely ignored.

These are not academic issues; lack of focus, not lack of resources, was at the heart of the Fort Hood shooting that left 13 dead, as well as the Christmas Day bomb attempt thwarted not by the thousands of analysts employed to find lone terrorists but by an alert airline passenger who saw smoke coming from his seatmate.

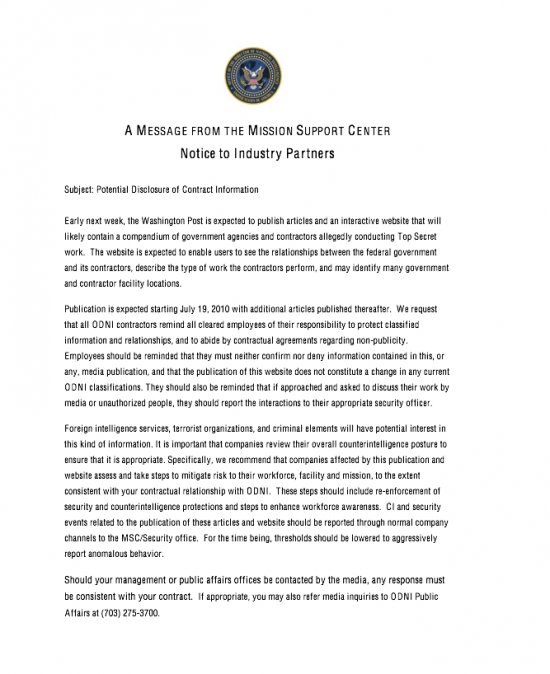

Not surprisingly, intelligence agencies have treated the report with some apprehension. Last week, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence circulated the following memo to its “industry partners,” which says in at least five different ways that intelligence employees shouldn’t give any information to nosey reporters:

(via Washington Times)

(via Washington Times)

In the wake of the report’s release today, Acting Director of National Intelligence David Gompert took issue with the report’s claims of government and contractor wastefulness, and released a statement of his own: (via Danger Room)

In recent years, we have reformed the IC in ways that have improved the quality, quantity, regularity, and speed of our support to policymakers, warfighters, and homeland defenders, and we will continue our reform efforts…. We will continue to scrutinize our own operations, seek ways to improve and adapt, and work with Congress on its crucial oversight and reform efforts. We can always do better, and we will. And the importance of our mission and our commitment to keeping America safe will remain steadfast, whether they are reflected in the day’s news or not.

Why the big freakout over what the Post admits consists of amassed publicly available information? The cynics will say there’s nothing new to see here, though the sheer amount of information and its user-friendly organization falsify that claim. The cable newsers will latch onto this small data point and turn it into a shouting match, probably about whether newspapers should write reports that could ‘endanger our national security’ or some other such asinine misinterpretation. The Slashdot crowd will say, with some merit, that the likes of Cryptome and Wikileaks have been doing this sort of thing for a long time now. In fact, a cryptic tweet sent by Wikileaks this past weekend — “Real change begins Monday in the WashPost. By the years end, a reformation. Lights on. Rats out” — seems to hint at their involvement with the project, although they’re not officially credited by the Washington Post.

One may groan to hear it, but there’s an Apple analogue here: Reports of the antenna problems afflicting the iPhone 4 were pretty common knowledge on the Internet just days after the phone’s release in North America, but it took stodgy old Consumer Reports‘ un-bloggy authority — and its rigorously documented testing procedures — to get Apple to budge. Who or what can “budge” in the face of Top Secret America is less clear; private contractors aren’t about to shamefacedly return their tax dollars and redundant government agencies won’t bashfully merge. And if past experience is any guide, the news cycle that arises from the Post‘s report will be shorter and more disappointing than one would hope, fixated on second- and third- order ethical hypotheticals instead of the hard work of actually confronting the data and what it means for America.

But Top Secret America will endure because literally, it will endure: As a database, as a resource for those few who will find things to do with it — hackers in the truest sense of the word — it’s of potentially much greater value than the Pulitzer-oriented old media pieces of the past, in which so much more work, constrained by the width of the news column, never sees the light of day, unless a memoir or book comes of it. Open notebook journalism is a fine thing for bloggers to discuss and invent; open spreadsheet journalism conducted with the muscle and the authority of the Washington Post behind it is an order of magnitude more difficult and more rewarding, and the importance of Top Secret America’s subject matter ensures that it will not go to waste.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]