Top 20 Akira Kurosawa movies, ranked worst to best

It should go without saying that Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa significantly influenced your favorite directors. With over 30 movies in a 57-year career, we will run down the top 20 films of his highly influential filmography, from “worst” to best, with some notes on each.

Key facts on Kurosawa

Born in 1910, Kurosawa didn’t become a director until his thirties, as he first worked as an artist. He was greatly influenced by his older brother, Heigo, who encouraged his art, film consumption, and left-wing political involvement. Following Heigo’s death by suicide in 1933, with their eldest brother having already passed, Kurosawa was left with a great void.

While training to become a director, Kurosawa worked as an assistant director, with the famed director Kajirō Yamamato being the most prominent figure in his development. He also became a highly sought-after screenwriter, which served him financially even as he became famous.

Most of Kurosawa’s influences were homegrown, including Japanese Noh and Kabuki theater and samurai culture. However, Western literature, such as works by Dostoevsky, Ed McBain, and Shakespeare, also significantly influenced him. American director John Ford’s Westerns also impacted his works, though he was sometimes criticized in Japan for this particular influence for being “too American.”

Kurosawa’s innovations in camera techniques, visual storytelling, and his ability to integrate Eastern and Western traditions with nuance, made him legendary. His investigation of human nature and social issues through film gave Spike Lee, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg a model for their eventual work.

Pretty good

One Wonderful Sunday (1947): The sensitive portrayal of everyday struggles through a neorealist context influenced many directors’ approaches to social realism.

Scandal (1950): Dealing with media ethics that would work even today, this critique of tabloid journalism and ideas of privacy still rings true.

I Live in Fear (1955): This flick is a rugged exploration of psychological trauma and social turmoil through the lens of nuclear anxiety in power-war Japan.

The Idiot (1951): Set in post-war Hokkaido, the director adapts Dostoevsky’s novel dealing with themes of innocence corrupted by society and the complexity of relationships. It was not initially well-received, but gained critical love in time.

Dersu Uzala (1975): This picture, with its incredible cinematography and “man vs. nature” themes would deliver Kurosawa the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. This placement should further indicate the quality of his filmography to come.

Now we’re really getting somewhere

Dreams (1990): This surrealist film originates from Kurosawa’s investigations of his dreams. He also manages to tackle environmental issues with well-shot dream sequences and magical realism.

Sanjuro (1962): The sequel to Yojimbo (1961) remains influential in the development of the bankable action-comedy genre.

Red Beard (1965): This humanistic media drama details Kurosawa’s character development and melding of fantastic screenwriting with the visual aspect of cinema.

The Bad Sleep Well (1960): A political thriller based loosely on Hamlet, he thoroughly indicts Japan’s corporate corruption.

Drunken Angel (1948): An early work that firmly established his signature look, texture, and themes. It is the beginning of his collaboration with Toshiro Mifune.

Must-watch

Kagemusha (1980): Set in 16th century feudal Japan, the film, which explores the hollowness of power, represents Kurosawa’s return to epic filmmaking after a down period. It was partially funded by George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola when the director struggled to secure Japanese funding.

Stray Dog (1949): A convincing and gritty police noir film, it portrays a realistic post-war urban Japan.

The Hidden Fortress (1958): One of the films that inspired Lucas’s Star Wars, Kurosawa’s storytelling from the proletarian characters’ perspective and his blend of humor and action have been widely imitated since its release.

Why haven’t you already seen these?

High and Low (1963): This is an absolute classic of a crime drama/thriller that combines social commentary with suspense. Its investigation of class division and warfare remains relevant today.

Yojimbo (1961): An incredibly stylish and cynical samurai film, it redefined the anti-hero archetype and has been remade numerous times, especially in crime and Western films.

Throne of Blood (1957): Kurosawa’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth absolutely ranks near the top in cinematic history. The Japanese Noh-inspired performances directly influenced numerous directors in their subsequent approaches to dealing with classic texts.

Ran (1985): You liked watching Game of Thrones? Yeah? This is one of its main cinematic influences. Ran is the grandest (and most expensive by Japanese standards of the time) adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear. The ambitious film explores themes of chaos, betrayal, and the (ironic) consequences of human ambition. Kurosawa’s attention to detail was so tight that he made arrows that were authentic for the period. Also, Toru Takemitsu’s film score for the win.

Rashomon (1950): The film offers four conflicting accounts of a single incident (the murder of a samurai and the sexual assault of his wife) to legendary effect. In fact, the overarching storytelling technique is called the “Rashomon effect,” as it delves into themes of ego, self-preservation, and the plasticity of memory and subjective truth. Its non-linear, multi-perspective narrative structure—specifically the development of the unreliable narrator—has been used in various media beyond film.

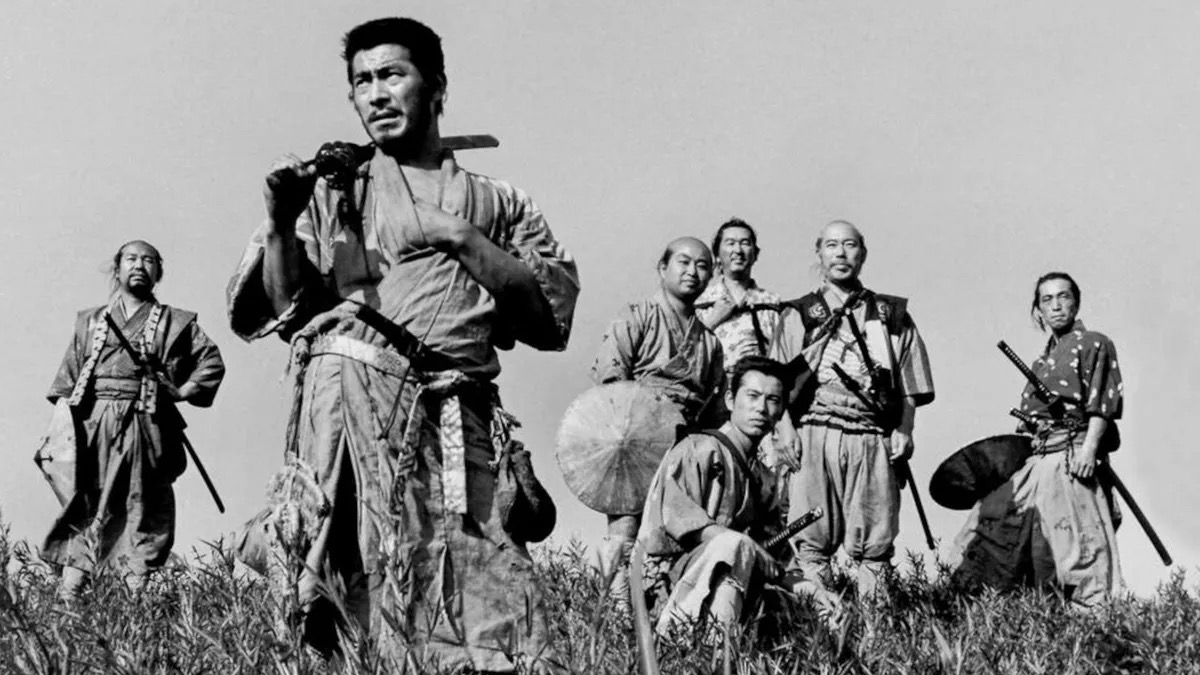

Seven Samurai (1954): There’s a decent chance that even if you’re not a film buff (like me), you’ve at least heard of the title of this legendary film. Set in 16th-century Japan, the story features a village of farmers who hire seven ronin, or masterless samurai, to ward off bandits who have plans to steal their harvest. The film pioneered using telephoto lenses to compress space through its action sequences and introduced the well-worn trope of gathering unlikely heroes for a mission. If the three-hour runtime scares you, imagine the glory of the epic, rain-soaked final battle—which required the rigging of a complex water pump system.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com