Akira’s Tetsuo Shima Is One of the Few Examples of a Well-Written Mentally Ill Antagonist

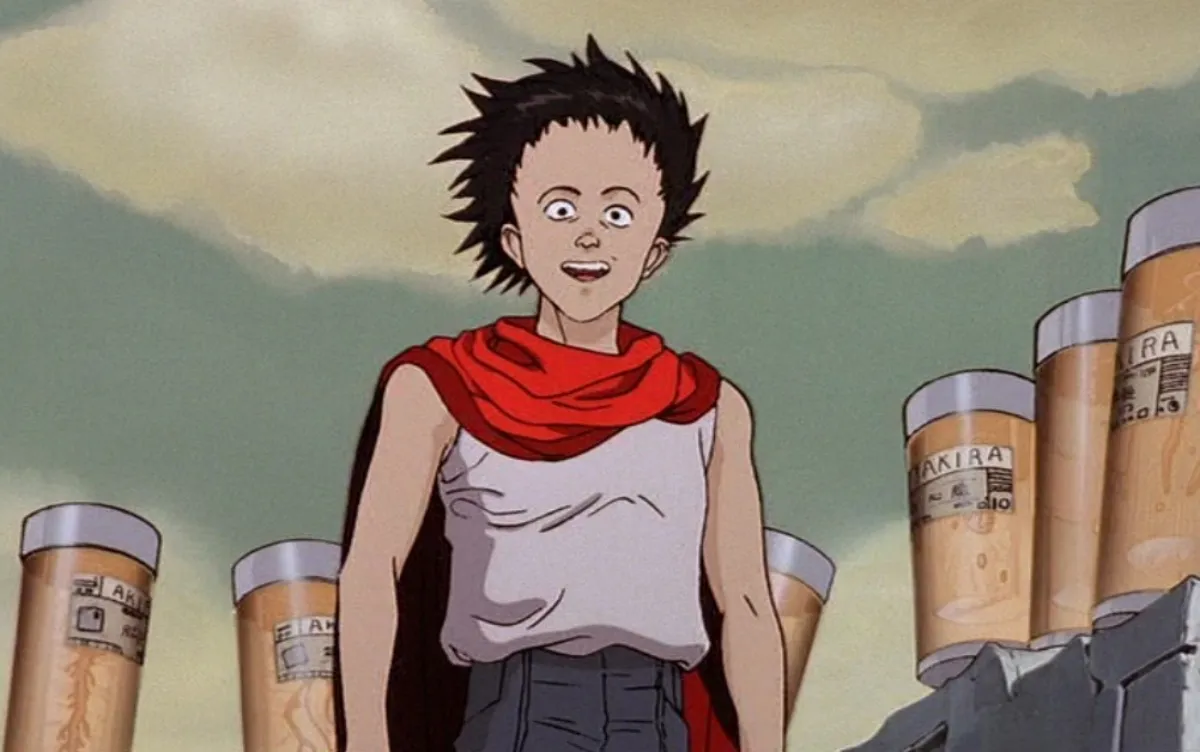

I am ... Tetsuo.

As someone who is mentally ill and deals with it sometimes in macabre ways, I am sensitive to the idea that not everyone can deal with their illness in that way. We are people who are living full lives, and characters and stories can only do so much to translate an entire lifetime of mental health into a compact narrative. Still, mental illness and “madness”™ are recurring themes in stories about a good person going bad because of “one bad day.” So, I wanted to examine one movie that I feel handled that well: 1988’s Akira by director Katsuhiro Otomo.

Disclaimer: all of this is personal, so I would love to hear where you agree, disagree, and where you feel like mental illness has been done well/poorly. We all live in our heads differently.

I’ve only seen Akira once, a month ago *rings shame bell*, and ever since, it has stuck with me for a lot of reasons, but especially the character of Tetsuo Shima. For those unfamiliar with the classic, honestly, I’d recommend stopping now and going to watch the movie. I managed to see it unspoiled for the narrative, and it was an amazing experience that I wouldn’t want to ruin for anyone. It’s truly a work of art.

Akira takes places in the dystopian year 2019 and tells the story of Shōtarō Kaneda, a leader of a local biker gang and childhood friend of Tetsuo Shima. Tetsuo, my sweet big-headed boy, suffers from an inferiority complex that leads to complications when his latent psionic abilities are awakened after a motorcycle accident.

In the world of Akira, nearly twenty years ago, a singularity destroyed Tokyo, leading to World War III, and while the city has rebuilt itself, it’s plagued by corruption, anti-government protests, terrorism, and gang violence. The singularity was caused by a child named Akira who, like Tetsuo, had very incredible psychic powers that were developed by the government, along with other special children called Espers.

Only going by what happens in the anime (there’s also a six-volume manga, also written by Katsuhiro Otomo), one of the things that’s super notable is the moment that Tetsuo’s powers really trigger. He has just escaped The Nursery and has stolen his friend Kanade’s bike. While riding, he’s attacked by a rival gang and badly beaten, unable to protect his girlfriend from being harassed, and has to be rescued by his friends. This moment explains the rest of Tetsuo’s actions and his thirst for power. He felt this immense moment of powerlessness and is determined, by any means necessary, to never feel like that again.

Tetsuo doesn’t “snap.” He’s a kid who has been given god-like powers, but was raised in a harsh dystopian society and has been taught that might makes right. He now has the might. The powers cloud his rationality because giving them up means losing this ability to protect himself and others. As the other Esper children insinuate to us, Tetsuo is too old, too traumatized, and has too little self-esteem to believe people really care about him until it’s too late.

Eventually, Tetsuo’s powers turn against him, and his body begins to transform into this grotesque horror that looks like a fetus. That is Tetsuo’s truth; he has all this power but wields it in a childish way because he’s stuck in a child’s mindset. In the end, before Akira takes him away, we hear Tetsuo crying out for help over and over, trying to protect the friend he was just fighting a little while ago, and being lost in the pain and horror of his existence.

I sob sometimes thinking about Tetsuo, because I find the character depressingly relatable.

There are a lot of examples of villains who become evil because of new powers or mental illness: Hal Jordan as Paralax, Jean Grey as Dark Phoenix in the X-Men films, and The Joker. A lot of these don’t work because they act as though mental illness completely changes the way a person is. There are some extreme cases where it doesn’t, but for people with depression, anxiety, etc., often times it only brings out things about yourself you that you are already feeling.

For Tetsuo, he mistook Kaneda’s concern and love for him as put-downs and emotional manipulation. He felt like his friends always wanted him to be small, but they just wanted to be his friend. It isn’t until Akira returns from his other plane of existence to stop Tetsuo that the young man can really understand that the people in his life cared for him the whole time—that all Kaneda wanted was to protect him, since they were both orphaned delinquents. As Tetsuo ascends to a higher plane of existence, we can believe that he finally understands that he wasn’t worthless. It just took him too long to get that.

While Akira is about the corruption of power at its core, I found myself really attaching to the emotional beats of the film, not just because of my own mental health state, but because I recognized something in Tetsuo. It’s dark, sad, and hurt, but it’s real and done in a way that seems earned, genuine, and about exploring his hurt as much as exploring his villainy.

That’s why it works for me where others have failed.

(image: Tokyo Movie Shinsha/Streamline Pictures)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com