Sorry, Your Art Has Never Been Apolitical

Take a stand or take a seat.

As I wrote about Chuck Wendig and Marvel’s decision to fire him for not being civil, one of his tweets leapt to the forefront of my mind. It was a discussion of how inherently political art can be. A quick Google search dug up a piece he had written on this for his blog, where, in his usual fashion, he managed to hit the nail on the head when it came to talking about inclusion, writing:

A lack of inclusion in narrative is one such choice — based on lazy tropes and outmoded prejudices, it’s a choice that refuses to acknowledge actual people and actual reality.

None of that is an excuse, by the way, to make the opposite choice lazily — it’s entirely worth seeing the line where inclusion stumbles into a host of other problems (white savior stories, appropriating narratives that are not yours to tell, injecting such inclusion with other shitty tropes), but that’s a reason to do it and try to get it right rather than simply not to do it at all. Because it bears repeating: not being inclusive in the work is a political choice. Stories are not real. We tell them. We make them up. We will them into being with our fucking minds.

It’s up to us to make them right and to tell them to the widest audience we can reach. Further, it’s also up to us to help support inclusivity outside the stories and among storytellers — inclusion shouldn’t just be on the page or the screen, but also behind the camera, behind the executive desk, behind the editorial and authorial pen. We have a lot of work to do, and choosing not to do it is no longer acceptable.

Earlier this week, I talked about how First Man didn’t sit well with me for the apolitical stance it took, because in its rush to appeal to mass audiences, it presented an all-white, mostly male look at the space race, with no commentary about that whiteness and maleness. At the end of the week, Wendig’s firing for his vocal left-leaning political stance makes me want to scream from the rooftops to stop making the political choice to be apolitical.

Representation matters. This is a sentiment I have written a thousand times over, that others have written a thousand times over. Inclusion in your story is necessary and, in this current political climate, almost a moral imperative. Art has always reflected the culture around it, and in 2018 the culture should not just be seen as white men fulfilling conservative wet dreams as the token characters of color or women look on. We need diverse stories to make up for years of the same story being told over with a slightly different white man in the lead, and because, simply, these stories are better for their choice to not just reflect a homogenized white world.

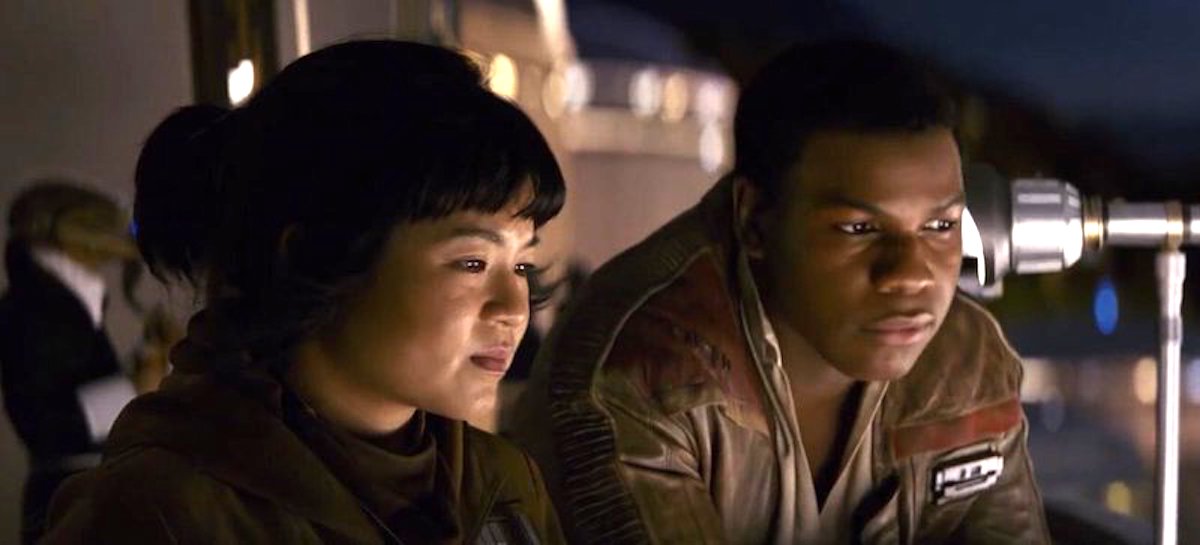

Of course, the trolls will scream that we need to keep political agendas out of our work when we talk about Black Panther, or Wonder Woman, or The Last Jedi. The simple act of having protagonists who are not white men is seen as a political agenda, something that the liberals of Hollywood are forcing down people’s throats. Never mind the political history of comics, or that Star Wars has always been about fighting fascism. These stories have always been political.

Worse still is the fact that they view an apolitical avatar as being a straight, cishet, able-bodied, white man. By default, that reduces everyone else to being the other, something inherently different from the norm. If you don’t think that helps kids learn biases and bigotry, you’re not paying attention.

Wendig’s work is political in that it does often directly tackle social issues, but him putting a gay man in a Star Wars book is not political. On the other hand, the lack of canonically gay characters in the Star Wars films and television shows? That’s a political choice. And yet, the reverse is believed to be true, because the existence of any other character has become political.

We can argue over whether our existence in the actual real world is political or not, but if we normalized seeing everyone represented onscreen, we could do a lot to de-politicize the act of existence in the real world. We need to normalize the telling of our stories because the same variant of sad white men struggling to feel masculine and fulfill the role of patriarch does not cut it any longer.

And as Wendig said, art is not made in a vacuum. We as writers create worlds, fill them with characters, and decide how the story goes. If your vision for your story is riddled with stereotypes and only includes white people, or straight people, then you are making a political choice even if you claim that politics aren’t affecting your decisions. Sometimes yes, you do want to make your work actively political through narrative or theme. But in a giant space opera, or a superhero film, or any sort of massive genre film, how is making it inclusive the political choice when there are running themes of doing the right thing and fighting evil?

It is time to challenge the notion that your choice to only tell white, cishet, able-bodied stories is somehow apolitical. Hell, it’s time to stop implying that a work having a political agenda is a bad thing. We’re talking about a medium that is inherently political and can’t exist without outside influence. A political agenda means you’re actually giving it more thought than just only writing something vague in hopes of appealing to a nebulous general audience.

If you have the platform to tell these stories, you have a responsibility. You can either uphold the status quo and continue to marginalize and silence other voices and stories, or you can take that political stance and actually effect change either by uplifting other voices or trying to share their stories in your work. That’s a fairly easy choice to make, in my opinion.

(Image: Lucasfilm)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com