Interview: Directors Bonni Cohen & Jon Shenk, Daisy Coleman On Starting Difficult Conversations About Sexual Assault in Audrie and Daisy

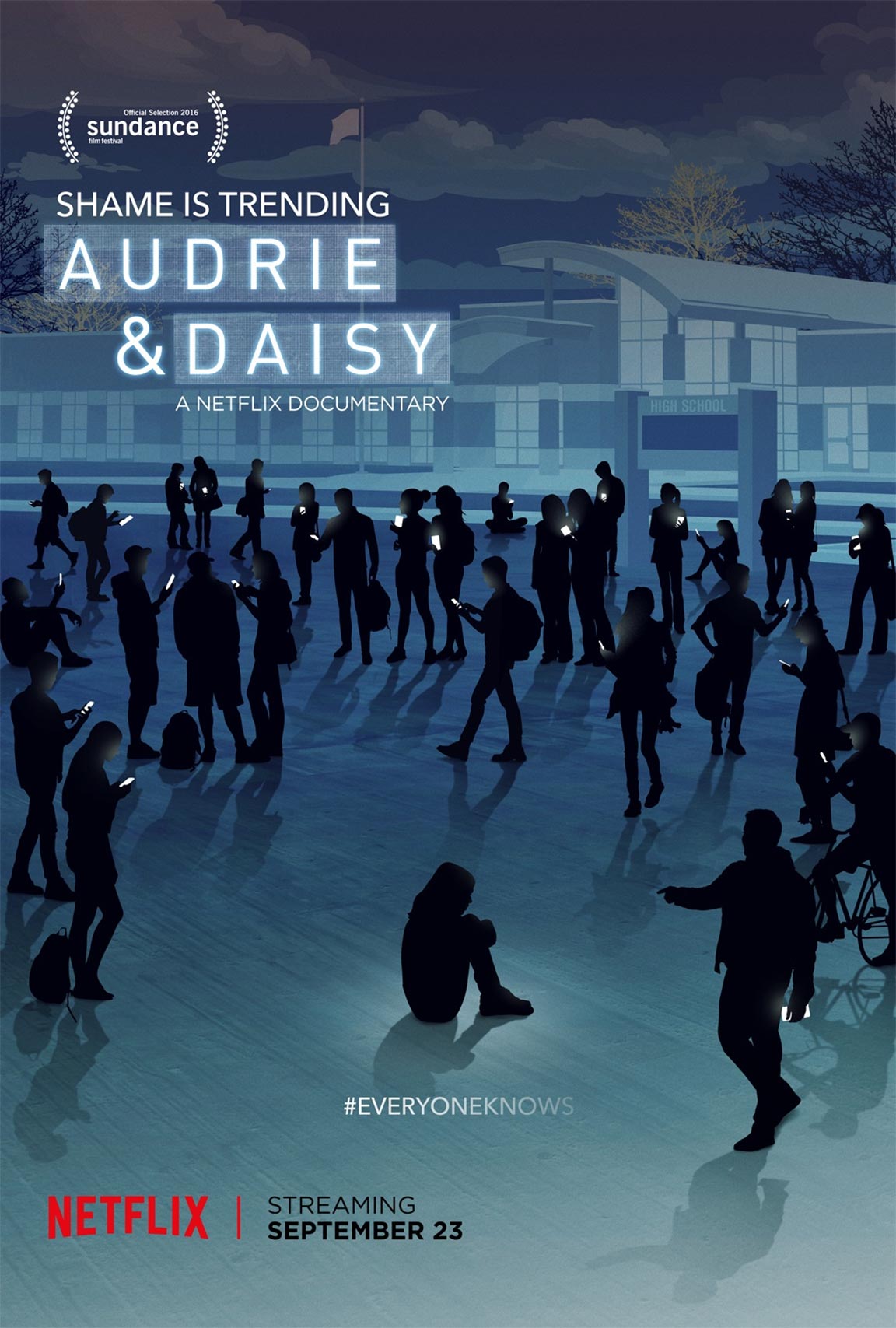

Audrie and Daisy is out on Netflix today, and it’s a documentary that’s both devastating and incredibly important to watch. The film traces the stories of Audrie Potts and Daisy Coleman, two teenage girls who were sexually assaulted in 2012. While Potts and Coleman didn’t ever meet, the two shared similar stories of social media shaming, case mishandling, and more.

I had a chance to speak to directors Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk about how they handled interviewing two of Audrie’s assailants, partnering with organizations, and facilitating this conversation. I also had the opportunity to talk to Daisy Coleman about how she hopes this film will push more people to support and empower survivors of assault.

TMS (Charline): The starting point of the film is 2012, but it seems like it’s only become more timely in a kind-of-tragic way. Were there any developments or surprises during production that shaped the final documentary?

Jon Shenk: Well, I think the very process of making a documentary is one where you’re constantly surprised because you get into this story generally and then you’re sort of almost hoping for surprises because that’s part of great storytelling–to find out more about your characters, to go deeper into the story. I think probably the biggest surprise though was the settlement agreement. We were following the Colemans and the Potts and we were actually near the end of production, near the end of shooting, when we got a phone call one day from the Pott family telling us that they had settled the civil case. They had filed for a wrongful death case against the perpetrators, the two young men who were boys at the time of Audrie’s death, and this was subsequent to the juvenile, criminal proceedings that ended with them doing some time in juvie in California.

Anyway, they had been pursuing this civil case and they settled and part of the settlement agreement was that the two perpetrators agreed to be included in our documentary and we didn’t know anything about this going in so we were surprised and we thought, “that’s a little strange–what do we do with this?” We’ve never done an interview in these kind of circumstances before and we came to the conclusion that we’d go ahead with the interviews and try to do it in a way–put it in the film in a way where the audience would be aware of the circumstances: that we had to maintain their anonymity, that they were, it was part of their punishment–so to speak–to sit in thees interviews. We wanted the audience to know that but Bonni says it very well, she always reminds me that we really were hoping for the film to be as much for boys as for girls. If we can get some glimmer of truth out of what they were feeling about what went down that night Audrie was assaulted, it was worth doing. We went into the interview with that attitude.

Bonni Cohen: The other shocking thing was that–I guess it isn’t shocking now that we know so much more about these kinds of cases–was just the proliferation of them over the course of the making of the film. Of course, additional cases came forwards, obviously the Stanford case got so much attention amongst others. There were many cases around the country that were going on and if anything it just kind of emboldened us to move forward as quickly as possible with the film, because we really think of the film as an opportunity to spark exactly the right kinds of conversations to get this out and start to make some change.

TMS: When you were talking about the John B. and John R. interviews, something that struck me was that while it doesn’t seem like they’re giving any new information it still feels very important to have their voices in there.

Shenk: That’s a great observation. It’s not like they’re spilling their guts about whats happening that night–there’s no breakthrough from a legal standpoint or anything. But I think that’s a part of the magic of documentaries. Real people telling their real stories has a really almost impossible to explain magical quality to how it can resonate with people watching the film.

We went into those interviews knowing we wouldn’t be able to show the live video because of the legal restriction of maintaining their anonymity, but we really felt strongly both in how we talked to them and interviewed them–treating them fairly as people but also in the animation that was based on the video that we shot of them, that we retain as much as possible of their humanity and their kind of personhood, so to speak. And we really wanted people to know that those were real people, and that, in many ways, what we witnessed that day was that these guys seemed like broken people. They seemed as much as they were guilty of hurting Audrie, of course, they were also kind of broken themselves by the lack of guidance they had gotten on what they’d done, what society thinks about this, and we walked away feeling quite sad for them and for us. That as a society we have so much work to do to lend guidance to boys like these earlier in their lives so that they have an ethical guidepost to guide them when they’re in high school.

TMS: Yours and Audrie’s names make the title and we’re always very aware in the film that Audrie isn’t there to speak for herself. I’m curious about how you see your relationship with Audrie after doing the documentary considering the similarities between your stories.

Daisy Coleman: I feel like after learning about Audrie’s case and who she was as a person, I almost took it as a responsibility upon myself to speak out for her since she didn’t have the capability to do so. But after meeting Audrie’s parents I feel like I almost learned who Audrie was on a more personal level. I definitely connected with her more because as I’ve learned she was an artist before she passed, just like me, and she just had so many similarities that connected us and I just feel like she’s not really gone.

TMS:What do you think you want people to take away from the documentary?

Coleman: I feel like, if anything, I want the audience to take this and realize that this could happen to anyone at anytime and that when it does happen it is most definitely not that person’s fault, in that they have the ability to become a survivor instead of a victim.

TMS: It’s definitely a film for social change, and anyone can really see themselves in it whether they’re, like you said, a boy, a survivor, a friend, or a parent. What has the reception been like?

Coleman: There’s been an amazing outpour of positive comments towards the film and where we’re going with this in this movement. There’s always going to be a couple of negative comments, of course, and you know, the block button is my best friend in situations like that. So yeah, it’s all just been really positive thus far and there’s so many survivors and victims coming forward now and it’s speaking to me and other participants in the film about how they wanna speak out and how they want to be part of the difference.

TMS: And something particularly present in these cases is the role of social media, which can be both a really horrendous thing, a well-intentioned thing that might bring unnecessary attention that invites harassment, and also people supporting and connecting with survivors. How do see social media now?

Coleman: I think that social media is definitely something–it becomes what you make of it. After my case went viral, it was a lot of negative feedback that I got from social media, but after receiving so much negative feedback I decided I would turn it into something positive and reach out to others survivors and victims and connect with them and let them know they’re not alone in their endeavors.

TMS: I know the film has also been using social media to promote this conversations, and building awareness about how powerful that platform can be.

Shenk: Absolutely. We felt like the social media element was really what makes our moment in time so different from the past. For example, we didn’t grow up with iPhones or Facebook and this technology and our lives were different because of it. It’s had an impact on our lives both for good and for bad. We really wanted to make the documentary feel like it was authentic to the time that it was made, so if you were a teenager watching this film, our goal was to hopefully make it feel like as pure a reflection of reality as possible.

We showed it to our kids and their friends as we were making the film to make sure of that, using things like Audrie’s Facebook transcripts, Daisy’s texts, transcripts from the night of the assaults. We tried to make it almost a third character in the film–it has strength and it has meaning. These things are faceless, nameless conversation that are taking place in computers, there are real people behind those communications and you feel it, hopefully, as an audience that those things that are having real life impact on the people doing them now.

TMS: On the other end of that, was talking to the sheriff, an older man who maybe didn’t get that guidance and actively reinforces that damage, was that challenging to do?

Cohen: They were equally as challenging, definitely. Because part of what we do, a big part of what we do is we end up in conversations with people whose opinions we don’t necessarily share. But they’re valid, they have a place, they have a perspective, and they’re incredibly important in terms of shedding light on the larger cultural norms, right? Because I think that Sheriff White has opinions and thoughts about what went down with Daisy’s case that resonates in other small towns and law enforcement in other small towns around the country. So was it tough to sit across from him and maintain journalistic ethic? Of course it’s challenging, but we were incredibly committed to really asking him the hard questions. You hear my voice in the film, because I just wanted to make sure he was really saying what I thought he was saying. I think it’s as important that a film like this represent and show these alternate opinions that are shaping what’s going on in these cases as it is to have Daisy included, in a way, because the ramifications are so deep.

TMS: And Daisy, your family has a very big role in the film. There’s a lot about how this was a big eye-opening experience for your brother. Did the documentary do anything to your family’s relationship with these difficult conversations?

Coleman: I feel it definitely made us all a lot closer because we all had to really open up this conversation and it’s something very intimate to talk about, especially with your family. I feel like it was a really great experience especially for my older brother because he eventually realized that what he was saying was not what a lot of guys live by in that he was actually teaching these kids some really substantial information.

TMS: I noticed that in the film you’re involved with the Semicolon Project and I saw the film has a lot of partnerships to continue the conversation and keep things going. Could you tell me more about those?

Cohen: Sure, well from the beginning of the development and research for the film we’ve had as a partner Futures Without Violence which is a national organization out of San Francisco run by Esta Soler, who’s actually one of the original architects of the violence against women act in the early ’90s–so she’s a real fighter and they’ve done really good work around education young kids, especially boys. They have around issues of violence a program called “Coaching Boys Into Men,” and RESPECT! campaign–lots of efforts to get educational material into the hands of parents, of coaches, of teacher to get these issue in front of our kids and get some action.

We’ve joined up with PAVE which is an organization for young women by young women run by Angela Rose out of DC and the girls in PAVE, of which Daisy is a part, all really met for the first time–they’d been communicating over social media, but they met for the first time in that scene in the film in Washington DC. They’re doing such great work, using the opportunity of these girls being out there with their stories to act in communities and put them in front of high school students around the country. That’s a second partnership we have.

We’re working now with RAINN, which is the organization that Tori Amos does a lot of work with, and she’s written an original song for the film which is just amazing. With her we’ve come into partnership also with RAINN for victims or survivors who feel alone and want an immediately contact, someone to reach out to, to support them. They do that incredible work really well.

We’re developing additional partnerships: we have curriculum developers that we’re working with and we’ve got discussion guides and educational material now for the film so when it launches schools, families, even teenagers on their own can look at these discussion guides and have a sense of how to spark the conversations.

TMS: As directors, how do you two think you want people to walk away from this film? When I was watching I went through anger, sadness, frustration, inspiration, just so many emotions.

Cohen: That’s what we wanted.

TMS: Was it tough to balance all those tones, so you wouldn’t walk away only angry or just upset?

Cohen: Definitely, we tried to have some humor. When you’re crafting a piece over a long 90 plus minute period of time, you inevitably put yourself in the place of the viewer and part of our job is to make sure we calibrate the emotions landscape of the film such that while you’re devastated, you’re not devastated to the point of no return. So we thought a lot about that, we thought about making sure that there’s some hopeful tones in the film.

Shenk: We’re movie-goers and movie fans as much as filmmakers, and I think that films are unique in that what they’re really best at is emotion. If you want to learn about the statistics of sexual assault there are articles to read. If you want therapy, maybe that’s best in a one-on-one or group therapy session, but films can do something that other things can’t do, which is it can give somebody a window into a world that otherwise they would never have.

So we go about our work in that way. We really try to give people an experience that they otherwise couldn’t have and we’re just getting an incredible response. I’ve had men say to me, for example, “This is the last movie I ever want to watch about teenage sex assault. It seems so scary and so dark, and yet now that I’ve seen it I want everyone in the world to see it,” and that’s a great response for us. We really, we would hope that this could be a very rich emotional experience for people to go through and then hopefully see something true about the world that they might not have otherwise seen.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com