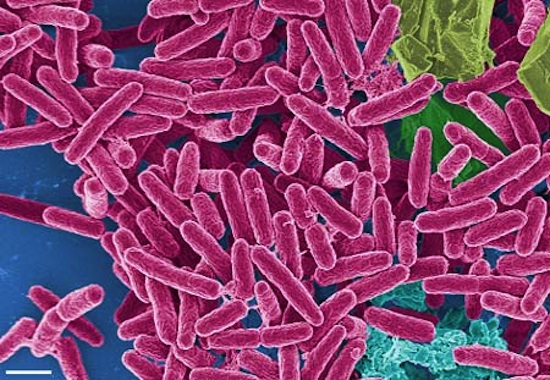

The Economics of Disease: Keeping Cells From Sharing Resources Can Collapse Bacterial Communities

The cells associated with cystic fibrosis are very good team players, working together to build thriving communities in patients’ lungs. Those communities have their share of freeloaders, though, who consume resources without contributing, and researchers at the University of Washington are working on a novel way to use those lazy cells to treat the disease. By making it more costly for cells to share so-called “public goods” that the entire community needs to survive, researchers made selfish cells more common, causing the bacterial community to collapse when resources run dry.

Most cells in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cooperate with one another — they listen to their neighbors, pool resources for the common good, and devote their energy to producing what is needed by the community. As the population grows, cells respond by producing more of the things their neighbors need in the interest of serving the whole colony. If they weren’t living inside of people’s lungs and drastically lowering their quality of life, it would be a pretty sweet little civil society.

Every society has its no-goodniks, and P. aeruginosa is no exception. The community also houses “cheater” cells, which are mutants that share public resources, but don’t produce goods for others around them. These tax-evaders of the cystic fibrosis world get all the benefits of living in the community without paying any of the costs.

By messing with a little known cellular sense known as “quorum sensing” — which gives cells a sense of how many other cells like them are around, and thus how many resources they need to produce — UW researchers tricked P. aeruginosa cells into thinking that the communities around them were smaller than they were, meaning that the cells produced less resources to share. That resulted in more cells becoming cheaters, as it became more and more inefficient for them to produce goods for the cellular society at large. You don’t need to be Adam Smith to predict what happened next. With more and more selfish cells drawing from a smaller and smaller pool of resources, bacterial colonies collapsed into ruin.

Quroum sensing is a young and poorly understood field, and this research is years from being an actual treatment for diseases in humans. If these early promising results pan out, though, it could pave the way for a whole new method of fighting bacterial infections without using antibiotics.

(via PhysOrg, image courtesy of CUNY)

- Sugar has some promise of fighting infections, too

- Plasma jets also try to break down bacteria’s strength in numbers to fight them

- And there’s no way you’re going to kill all the bacteria in a pepperoni, so don’t even try

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com