Why Justin Lin’s Teen Crime Film Better Luck Tomorrow Still Resonates With Asian Americans

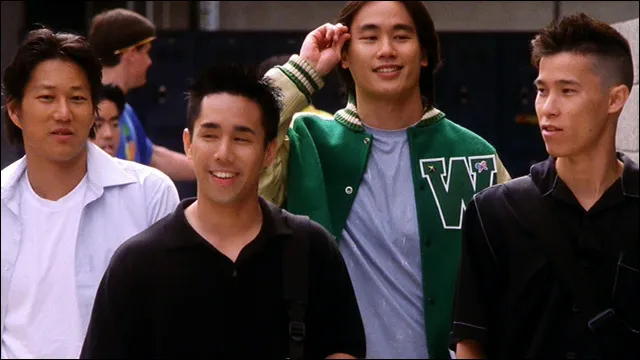

Pre-Fast and Furious, Justin Lin directed Better Luck Tomorrow, a crime-drama film. The 2002 film stars Parry Shen, Jason Tobin, Sung Kang, Roger Fan, and John Cho. Centering around a group of Asian-American high schoolers who excel at both academics and extracurriculars, Better Luck Tomorrow endured long past its first release as it was one of the few films starring all Asian-Americans without martial arts, a relatable white insert, or any kind of mysticism. It was a film about suburban youth culture (the first shot is of a gate community opening its doors), as high-achieving students grow bored with their conventional paths and begin rebelling with schemes, crime, and eventually, murder.

Our main character is Benjamin Manibag, whose group of friends, Virgil Hu, Daric Loo, and Han Hu, begin committing small crimes: stealing computer equipment, creating cheat sheets and selling them, and suddenly, a request from Ben’s nemesis (his crush Stephanie’s boyfriend), Steve Choe, to rob his mansion—what Choe calls a “wakeup call” for his parents. In an attempt to punish Steve, or perhaps get back at him, they plan to attack him instead, only to end up killing him—they don’t mean to at first, but amidst panic it very much becomes an intentional act.

As Crazy Rich Asians is right around the corner, it somehow feels appropriate to revisit Better Luck Tomorrow, a film that couldn’t be more different in scale or premise, yet occupies a similar kind of conversation about Asian representation, class, and rebellion. Both films also face the same consequence of underrepresentation, which is that when there are few films with Asian-American casts, they face more scrutiny and pressure to be everything to everyone.

Last year, the Los Angeles Pacific Film Festival opened with a screening of Lin’s film in response to Scarlet Johansson taking on the lead role in Ghost in the Shell and The Hollywood Reporter wrote that the film “continues to resonate with Asian American Hollywood after 15 years”.

Better Luck Tomorrow was inspired by the story of Stuart Tay, a high school student in Orange County who was brutally murdered by five other students wielding baseball bats and a sledgehammer. The case garnered attention because all the boys involved, save one, were wealthy, smart, and Asian-American. One was Ivy League-bound and tied for valedictorian. They had great SAT scores. They volunteered. The question appeared over and over: Why would they want to kill someone?

The Orange County Register called it “The Honor Roll Murder.” The name stuck. One line from the Chicago Tribune writeup in 1993 lingers in my mind: as the boys sat in the police station, the policeman watching them reported that their faces were completely blank with one “manacled to his chair, doing his calculus homework.”

There’s a few things in that image that strike me: It reminds me of how homework, clubs, and studying in Better Luck Tomorrow feel like something done in autopilot, achievements that are so naturally expected and taken for granted that they feel simultaneously like an inextricable part of your identity and not part of who you are at all.

Mentions of the Chinese mafia, a jealousy for a former girlfriend, or suburban gang fights were floated as motives. Andrew Ahn of the Korea Times blamed the “lack of moral education” in schools and said the boys were “Americanized.” (Robert Chien-Nan Chan, identified by many news stories as the ringleader, was later diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, but the diagnosis unfortunately didn’t help his case.)

The answer in Better Luck Tomorrow is pretty clear, though: They were in over their heads. Unlike the case of Stuart Tay, it seems that Ben and his friends have gotten away with the crime, if only in legal terms—it’s clear the psychological damage on each of the boys is profound, and Virgil attempts to kill himself.

The grittiness, violence, and wild improperness of the film was part of what made it such a big deal. Personally, a bunch of my friends and I thought it was exciting to see Ben and his team steal and lie and scheme and defy what society expected of them, their straight As serving as alibis, and their school clubs covering for them. It was exciting to watch them defy the meek stereotype. Of course, that wasn’t a unanimous reaction: An audience member at Sundance criticized Lin for portraying Asian-Americans poorly, leading Roger Ebert to defend the film by responding,

“And what I find very offensive and condescending about your statement is nobody would say to a bunch of white filmmakers, ‘How could you do this to your people?’ … Asian-American characters have the right to be whoever the hell they want to be. They do not have to ‘represent’ their people.”

My cousin, who was at the same high school the Tay murder happened, told me that, when he went to college, people would know the school as “that school with the Asians and murders.” Just over a decade later, I would go there as well, and the story of Tay would be repeated almost like a fun fact, a sensational history, in what feels like an otherwise conventional and drab suburban school, that people could excitedly claim through proximity.

This is to say, there is a gleefulness to resisting the “model minority” myth that painted Asian-Americans as boring—one that allows films like Better Luck Tomorrow to succeed, but also one that might leave us less horrified than we ought to be. Lin’s film, however, appears to try to curb the danger of glorification or spectacle throughout.

We see this in its use of guns: Derek pulls a gun on a classmate who picks a fight with his friends, throwing racist remarks and heckling them. Immediately, the white student cowers in fear and is helpless—Virgil goes from thrill to fear in a dramatic monologue afterwards, but the gun keeps returning as a symbol of power. Virgil pulls his gun on Derek in another episode, and it’s clear that he sees it as a means to exercise power, and some twisted notion of respect, that he otherwise wouldn’t have.

It’s this same gun that later accidentally goes off, in a struggle that ends with the boys killing and burying Steve. It’s the same gun that Virgil later almost fatally injures himself with. Along with the way, the boys are constantly baiting each other with insults like “dickless,” obsessively talking about getting laid, and other kinds of gendered insults. Better Luck Tomorrow is much more than a tale about the thrilling double life of Asian-American men.

The glee of stereotype-defying could have very easily turned into a macho fantasy of hegemonic masculinity—male empowerment as a replication of white power rather than a dismantling of it. However, it never seems to suggest that these boys should stick to their studying and college apps. It instead offers a difficult question about disaffected adolescence, and where these boys should channel their discontent and rebellion.

In Nary Kim’s article for the Asian American Law Journal, “Too Smart for his own Good? The Devolution of a ‘Model’ Asian American Student,” Kim looks specifically at Lin’s film and its adaptation of a real-life murder case through two tropes, both embodied and shattered by the bright, studious characters that also commit murder: the model minority and the yellow peril.

Kim writes that the murder was reported on as a meticulously planned, sinisterly masterminded craft that reflected how stereotypes could amplify guilt (compare this, say, with how young white men are spoken about as having their lives ahead of them, or as full of potential). Of the Asian-American community’s struggle with recognizing with increasing youth delinquency, Kim theorizes that this kind of willful ignorance might be seen as a resistance to yellow peril that prevents any kind of meaningful intervention.

“Beyond the universal truth that all teenagers will experience some form of angst,” Kim writes, “it seems that Asian American students are uniquely predisposed to undergo a crisis of identity—a maddening urge to reject the categorization of studiousness and nerdiness that naturally befalls them by virtue of their race and embrace a delinquent alter ego inspired by the yellow peril stereotype.”

The success of Better Luck Tomorrow and its lasting legacy is not just because of its casting, but because of its urgent insight into this “crisis of identity,” a deeply personal and political struggle that—the ensemble cast shows—everyone handles differently, and not everyone survives.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com