Casual Homophobia at Supernatural Conventions Just Won’t Die

In a video taken at a convention center in New Jersey in 2013, a young woman comes up to the microphone to ask Jensen Ackles, a cast member from the CW’s long-running horror-adventure show Supernatural, a question.

Before she gets into what she wants to know, she identifies herself as bisexual, and the crowd groans and giggles. When she then attempts to ask about whether a particular episode in the show’s eighth season might imply something about a character’s evolving understanding of his own sexuality, there is more groaning, and people begin shouting.

The actor says he’s going to “take a cue” and pretend not to have heard the question. He tells the question asker not to “ruin it for everybody,” and the girl ends up apologizing to him: “I do not mean it as disrespectful at all.” She does not finish the question.

One particularly talked-about incident among many, this moment and its aftermath were framed at the time as a “fandom meltdown” in a subculture “divided over Destiel,” the idea of a romantic relationship between Supernatural characters Dean Winchester (Ackles) and Castiel (Misha Collins). Notably, the question that day wasn’t about Dean and Castiel at all, but about a scene where Dean responds to the flirtations of another male character named Aaron with a flustered, blushing explanation that he’s working, and then walks into a table on his way out the door.

In the DVD commentary, Ben Edlund, the writer of the episode, credits Ackles for the scene’s ambiguity. He played it, according to Edlund, “right down the middle,” implying the “potential for love in all places.”

The surreal disconnect between the content of the scene and the way this person was shamed for bringing it up—as well as the simple idea that this young woman had a right to exist as a queer person in public without being laughed at or shouted at—got buried under discussions of shipping and Supernatural fandom as a zoo exhibit of hysterical girls.

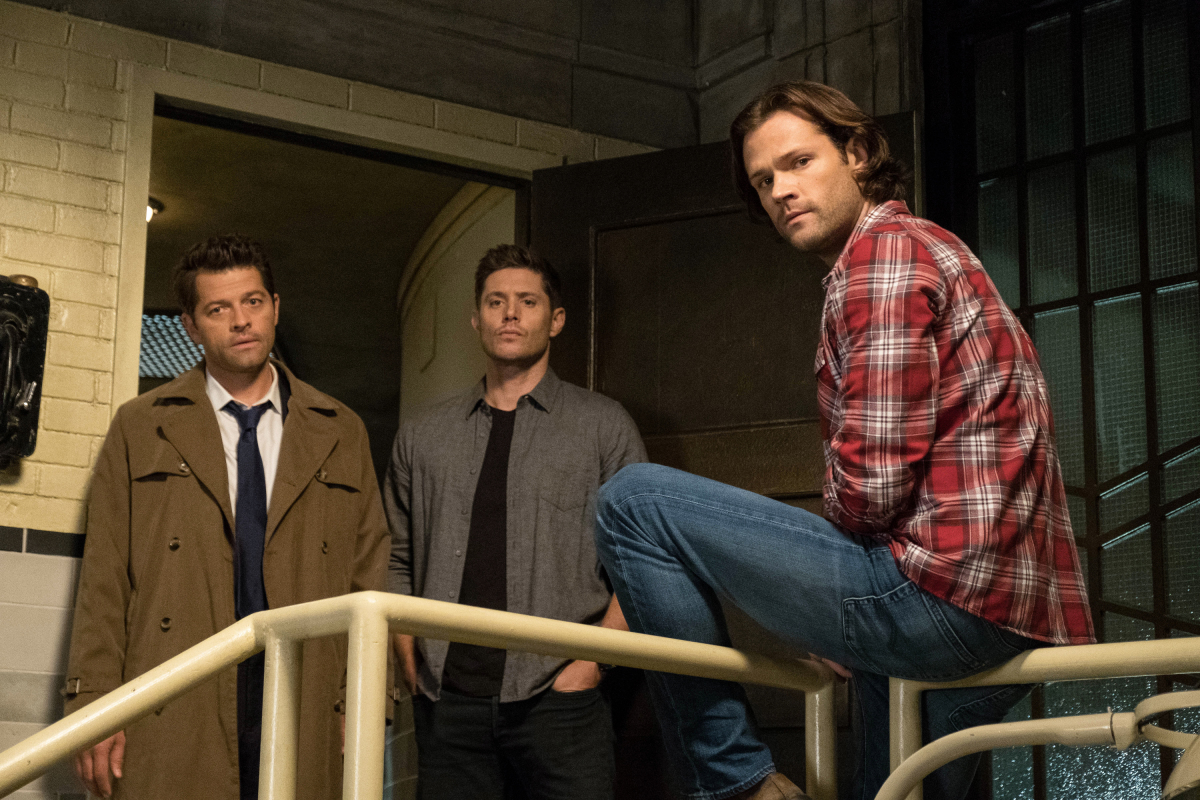

(The CW)

Destiel and queerbaiting

Over the years, Dean and Castiel, one of the most popular relationships in the history of fan fiction, became something of a synecdoche for tension surrounding whether or not gay themes—and gay fans—”belong” in Supernatural. LGBTQ+ people make up such a large and important segment of Supernatural’s audience that, in both of the two episodes where the characters encounter groups of fans of the in-universe Supernatural books (a conceit designed to enable meta jokes about the show and its fandom), there is a gag where Dean realizes with embarrassed bemusement that he is looking at a same-sex couple.

Emily Raymundo’s outstanding 2019 essay White Men—And the Monsters Who Love Them discusses the complex reasons why queer women have flocked to Supernatural; Darren Elliot-Smith’s “‘Go Be Gay for That Poor Dead Intern’: Conversion Fantasies and Gay Anxieties in Supernatural,” from the 2011 book TV Goes to Hell, examines its appeal for queer men. In short, we were there from early on, carving out our own spaces in the ultimate all-American macho pop culture. But, as Raymundo asks in her piece, is subculture still subculture when it’s being sold to you?

Supernatural has been central to discussions of queerbaiting, a type of deceptive promotion where a television show or film draws in an LGBTQ+ audience with ambiguity, jokes, or small gestures, but doesn’t actually include queer stories and characters in the way it promises or hints at, as a gag or to “play both sides”—and also retain conservative viewership.

While the show’s canonical inclusion of LGB characters (let’s be honest: no one was ever trans in a recognizably human way) tended to be brief and painfully awkward, gay sex jokes, ambiguous scenes, queer references, and blatant fake-outs were relentless onscreen.

Things were no better offscreen

Meanwhile, offscreen, the idea of queer people, particularly queer men, was relegated to one uncomfortable punchline after another: from Jensen Ackles referring to Castiel as “the gay angel” and then making a “yikes!” face at the camera in a behind-the-scenes video from 2010, to whatever this was from the lead actors’ bodyguard (who appears with them at conventions) in 2013.

There’s plenty more beyond that. There was Jared Padalecki (who costarred as Sam Winchester) saying in 2014 that the fake heaven a villain makes for Castiel in Season 9 was originally supposed to be full of pictures of Dean because “the writers thought it was funny” but they decided against it because “it would have ruined the show” if people took it seriously.

There was Jensen Ackles reading Castiel’s lines in a stereotypical lisping gay voice to the raucous laughter of Misha Collins and the crowd in 2016, or joking about a frequent setting called the Men of Letters bunker as “not the bunker of men … that’s for Cas” in 2019.

(The CW)

The gag reels are full of actors pretending to kiss and doing things like this. Year after year, Supernatural and its surrounding culture—on set, at promotional events—seemed simultaneously deeply uncomfortable with non-straight sexuality and deeply preoccupied with it.

Castiel’s declaration of love

Fast forward to the present. Supernatural has ended after fifteen years on the air, the longest-running live-action fantasy show in U.S. history. In the third-to-final episode, Castiel gave a long dramatic speech to Dean in which he revealed that “the one thing I want is what I know I can’t have,” told him he loved him, and promptly died.

Dean made no reply during the scene, and Castiel was barely mentioned in the following final two episodes. The ending was considered by many queer viewers to be far too little, far too late at best, and at worst, as one reviewer termed it, “bafflingly horrific,” but it was something.

(The CW)

Collins referred to the scene as a “homosexual declaration of love” and, at Memento Con 2021, acknowledged that “they literally used to have at conventions a little list of things that people weren’t allowed to talk about, and one of them was [Destiel].” When it came up during those early years, “the whole audience suddenly went into slow motion, ‘Stop it!’ Like I was crossing this line.” However, he went on, the culture has since changed, and “it just suddenly became, ‘It’s okay. We can talk about these things.’”

Can we? At a Supernatural convention this October in Colorado, a woman at a panel with Ackles and Padalecki came up to the microphone, explained that gay representation was important to her because she is the mother of queer children, and asked when it became clear to the actors that Cas loved Dean with a “romantic, deep love.” Here is a chunk of Jared Padelecki’s long response:

It doesn’t mean, like — I say that with my friends, I say it with Ackles, like, “Hey, I love you, man.” It doesn’t mean like, “I wanna take you to a hotel room,” it just means that I love you. And so that was, the — the — the point of the relationship, story-wise, is that they could love each other, you know — Sam and Dean loved each other, it wasn’t a show about incest. Cas and Dean can love each other, it’s not a show about — it’s not a show about heterosexuality or non-binary — it’s a show about, hey, you can choose to live your life with love, not, hey, this means they wanna make out. It’s not about that. It’s about — I can tell my son, “I love you,” and it’s not that I want to do something to or with my son, I just love my son. My daughter can say the same thing. So that wasn’t, I’m sorry, that wasn’t the point of that scene.

Treating any queer feeling as inherently about sex acts, and same-sex romantic relationships as less normal or less meaningful than other types of relationships, is, of course, homophobic, and bringing up incest and pedophilia as equivalent is shockingly so.

Yes, there were people out there who shipped the two brothers. No, that does not make Padalecki’s response more appropriate. If somebody brings up the concept of “romantic, deep love” between two people of the same gender and your first thought is, “This is just like that time I saw incest porn on Twitter,” that is a you problem, my guy.

Not to mention that interpreting Castiel’s confession scene as some kind of platonic bro love declaration doesn’t make any sense at all; in that case, what is Cas saying he wants but believes he can’t have, and why is it a surprise to Dean, who is already his best friend?

Padelecki then meaninglessly peppered in some politically correct terms (“you can be any part of the LGBTQIA”), as if a list of letters one is theoretically supposed to be cool with is all we’ve learned. The response was, frankly, unhinged. Ackles agreed with him and gave his own milquetoast response about how Castiel’s love can’t be understood in human terms.

In a video of a different panel at the same convention, this time with Misha Collins and Alexander Calvert—who plays Jack, the half-angel, half-human adopted son of Cas, Dean, and Sam—an attendee begins asking a question about Castiel’s final monologue. At the words “confession scene,” the convention employee standing nearby jerks to attention and shakes her head at the question asker with a sharp “nmm-mm.” The attendee says, “No? I’m not allowed to ask about the confession?” When Misha Collins replies, “Yes, you are,” the employee backs off.

(SparkCBC)

Note: A reply from Creation Entertainment’s customer service about October’s con was shared with me by an individual who sent a complaint. The customer service agent’s explanation was that the convention employee, mixed up after the long pandemic break, was “going by the rules for other shows” which ban “questions of explicit sexual nature” and that the “specific Team Member will no longer be allowed to work the microphones during the Q&As for SPN shows.”

What could have possibly been considered of “explicit sexual nature” by anyone about the mere mention of a scene where one man tells another I love you (platonically, according to Jared Padalecki!) while standing a full foot away from him is unclear. The email also reiterates that Creation is not responsible for what speakers say, a disclaimer that appears on their website, and brings up the customer service agent’s trans son who works at events as evidence of the company’s inclusiveness.

The pattern continues

Two conventions, eight years apart, the same bizarre tension as queer content casually acknowledged elsewhere is suddenly treated as inappropriate or imagined, as if the whole room has sidestepped into an alternate universe. The reason it’s still necessary to talk about things like the 2013 incident at the top of this essay, which would otherwise be minor relics of our social growing pains and worth forgetting, is that they are part of a pattern that has, like Supernatural itself, continued long past its expiration date.

No one involved in any of this stuff has ever said so much as a cursory “sorry” or—other than Misha Collins, only partially and after over a decade—even admitted that there may ever have been an issue in the culture at all. Why are Supernatural conventions still such a minefield when it comes to queerness?

I remember the rash of posts defending Jensen Ackles, even from people who identified as pro-LGBTQ+, after the New Jersey convention in 2013. He wasn’t scolding the person asking the question, many said, but the audience for interrupting her (the video makes it clear that this is not the case).

Someone claiming to be the question asker herself made a post on Tumblr explaining that she wasn’t upset at either the speakers or the bodyguard (yes, that one), who told her not to ask the question and instead “just thank them and go.” The post says that she also apologized to the bodyguard and asked him to convey to the actors a second time that she “meant no disrespect.”

Similarly, some acted as if the “gay angel” comment meant we were seen, and so did the video of Ackles doing the stereotypical lisping voice for Cas. Supernatural’s particularly toxic brand of celebrity worship can spin microaggressions into gold. Add to this that many of Supernatural’s LGBTQ+ fans were and are very young and may not have a frame of reference for being treated with respect, and you get a recipe for zero accountability for the people on stage, the people facilitating the event, and the people in the crowd.

However, it’s not as if there wasn’t criticism after the NJCon incident; there was, enough that it briefly trended on Twitter. It was just that nothing changed.

(The CW)

Why has the criticism been ignored?

Supernatural is an odd case. While its LGBTQ+ audience is commonly considered to have driven its long term success, it also has a strong Republican viewer base. Its 15 years on the air straddled a period of immense social change surrounding LGBTQ+ people’s place in American culture.

As public attitudes have changed in fits and starts, the undercurrent of homophobia in Supernatural’s subculture has stubbornly held on even when people have voiced their frustrations with it, arguably due in part to the way that Supernatural’s status as a niche product—its convention scene more niche still—insulates it from mainstream criticism.

Complaints simply echo into silence; the distant, shrill cries of the terminally cringe. After all, why should we care what happens at Supernatural conventions, which can notoriously be kind of pathetic and weird anyway?

These actors are paid thousands of dollars for these appearances; three more are scheduled in 2021 and ten in 2022. They attract hundreds of attendees, are viewed by tens of thousands of people on YouTube, and are referenced in the material itself.

It’s common knowledge that Supernatural has spent years courting and profiting from a very visible young queer audience.The company that puts on the official Supernatural conventions also runs conventions for Game of Thrones, Stranger Things, Lucifer, and The Vampire Diaries. The CW cultivates a progressive reputation.

The whole long, weird story of Supernatural’s contentious relationship with its queer audience is a sobering reminder that companies aren’t obligated to care about inclusion when it’s not profitable. It’s an illustration of how insular subcultures and celebrity cults of personality can breed unchecked asshole behavior. Ultimately, it shows us how, under the right circumstances, people can be sold their own humiliation.

Posing with all the rainbow flags and filming all the vague diversity promos in the world mean nothing when you’re still treating queer people’s perspectives as warped or marginal, fun to laugh at but distasteful to discuss sincerely. In a time when LGBTQ+ people are still at a higher risk of mental health problems than their cis and straight peers, are almost twice as likely as their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts to suffer from a substance use disorder, and continue to experience disproportionately high suicide rates, the attitudes we perpetuate matter.

Yes, even at an event for a silly TV show about shooting ghosts. Supernatural has always gotten away with treating its queer audience like a demon it’s been forced to deal with, but I don’t much feel like being the monster in anybody’s closet anymore. It’s time to turn on the light.

(featured image: Cate Cameron/The CW)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com