Clarence Thomas Hates Social Media, but Not in the Good Way

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is in the news today for firing a warning shot in an ongoing battle over if the government can regulate social media. The salvo came in a concurrence opinion in which no other justices joined, written by Thomas, in a decision dismissing a case as moot. The case had to do with if it was a violation of free speech for President Trump to block people on Twitter. What Thomas said at first seems good: that social media is basically like a public utility. But the underlying implication of the opinion is not good news for free speech.

So, to understand what Thomas is saying we need to understand a few things. First, the case itself. The lawsuit was filed by petitioners who were blocked by Trump on Twitter and who claimed that it was an infringement of their first amendment rights for him to do that, because being blocked from what they claimed was an official conduit for government information amounted to Trump illegally silencing their viewpoints. I’m personally not sure that that argument holds water, but since Trump was permanently banned from Twitter last year and isn’t President anymore, the entire case is now moot, meaning any decision wouldn’t matter, so it’s been thrown out.

The decision today was a weird hybrid, where the Supreme Court agreed to look at the case and immediately agreed that it should be dismissed, so the case is pretty much over. But Thomas took it as an opportunity to broadcast what he thinks about social media to the world. His opinion here is not binding and has no legal weight and isn’t precedent, but it’s still a very big deal because it’s an outline for an argument that threatens the way the internet works.

Thomas starts out by saying something that everyone can actually agree on: that the law as it applies to social media is evolving and difficult to determine, and that we can’t really use old precedent to make decisions on this new form of communication. Thomas writes, “applying old doctrines to new digital platforms is rarely straightforward.” He goes on to address: if we believe the petitioners, if an elected official’s Twitter is a source of important public information, then why is it okay for Twitter to shut that down as a private company, as in the case of banning Trump?

That’s honestly a tricky question, and Thomas correctly notes, “We will soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.” But then he goes further and declares that if Trump’s Twitter feed was a source of vital public information, and that Twitter, in general, is such, that it would make Twitter or all social media what’s called a “common carrier.” That means it’s a utility that all people are entitled to use, like an electric company. He also highlights that internet companies are so big and influential that they make it hard for alternatives to succeed, meaning a few companies have a big influence on what gets seen and how and who gets to use it.

“It changes nothing that these platforms are not the sole means for distributing speech or information,” Thomas writes. “A person always could choose to avoid the toll bridge or train and instead swim the Charles River or hike the Oregon Trail. But in assessing whether a company exercises substantial market power, what matters is whether the alternatives are comparable. For many of today’s digital platforms, nothing is.”

And again, he’s not wrong here. This is outsized control of the flow of information by a few big companies is scary. But what Thomas is implying here is that common carriers like, say, Facebook or Google, or Twitter, should, like other common carriers, not be allowed to exclude people unless they have a really good reason to do so. The implication is that Twitter did wrong by banning Trump and that attempts to ban people based on things like being racist/misogynistic/pro-Nazi assholes, disseminating conspiracy theories, or promoting violence are not good.

The other thing Thomas takes aim at, that Trump himself wanted to undo, is 47 U. S. C. §230, also known as section 230 or the words that created the internet. This tiny section of law makes internet companies immune from legal liability as publishers of content. Meaning someone can’t sue Twitter or Google or any internet company for “publishing” content that’s offensive, dangerous or illegal etc. Trump and others wanted, and still want, to get rid of that and open up the internet to lawsuits and more regulation.

Thomas seems to want it both ways, much like Trump. He implies that section 230 is bad and that there should be more regulation and accountability online, but he also implies that platforms shouldn’t be able to exclude people. So, everyone is entitled to use the internet but the internet should be more regulated? Overall while the issues Thomas raises are real, his conclusion is confusing and tricky, but the fact he’s bringing it up at all opens the door for lawsuits on this from both sides.

“As Twitter made clear, the right to cut off speech lies most powerfully in the hands of private digital platforms,” Thomas wrote. “The extent to which that power matters for purposes of the First Amendment and the extent to which that power could lawfully be modified raise interesting and important questions.” This is a debate that’s far from decided, and if people who share Thomas’s opinions have their way, it may end up being the Supreme Court that takes up the question in the future.

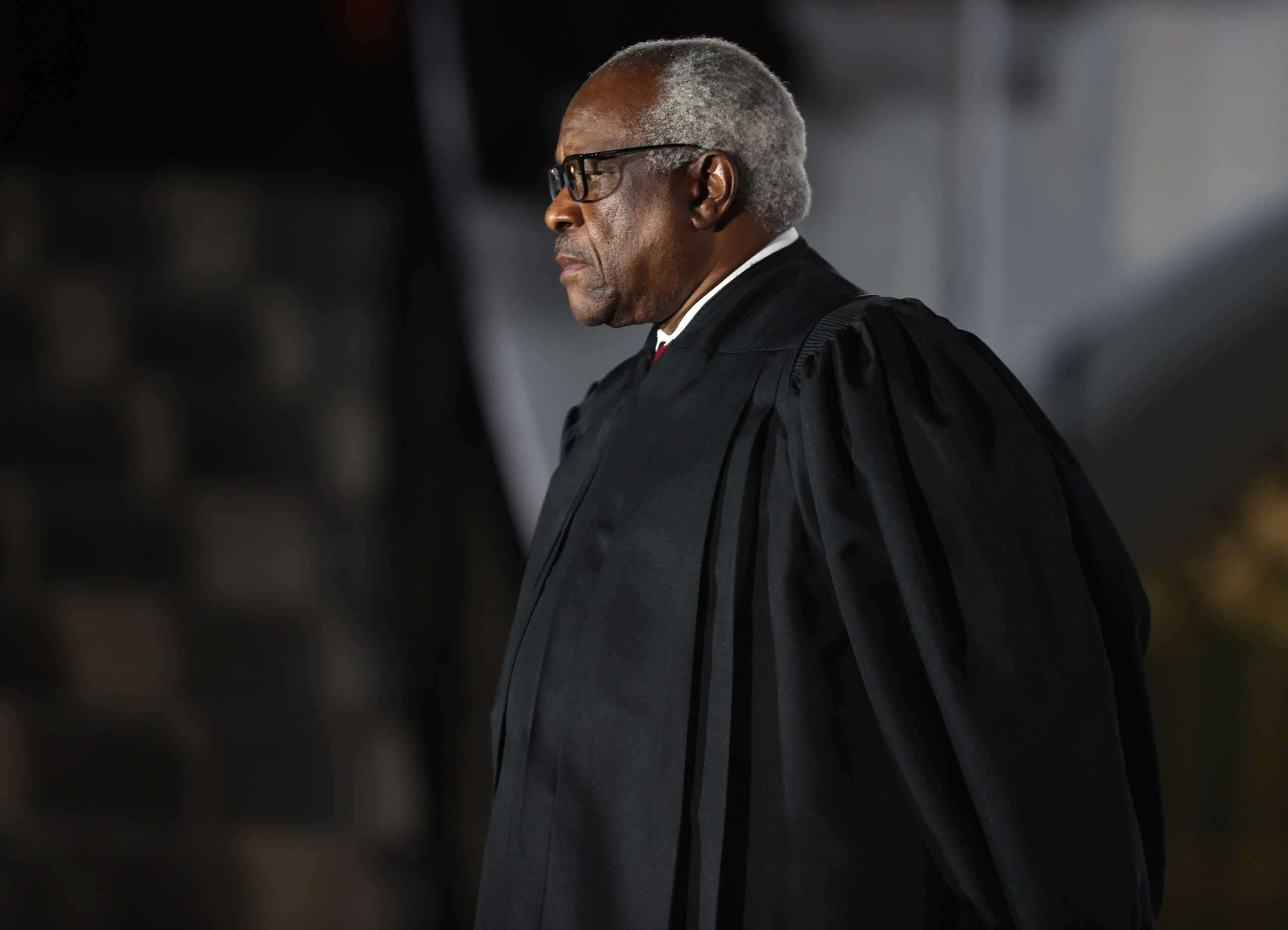

(via NPR, image: Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com