Even Without Book Bans, Publishing Has a YA Issue

Young Adult (YA) literature has found itself under attack from an increase in book banning and censorship. Right-wing groups like Moms for Liberty have set their sights on YA literature, and have succeeded in removing countless titles from school districts and local libraries. Some of the most common targets are books that address topics like abuse, racism, and LGBTQIA issues. Right-wing groups raise outrage by wrongfully classifying YA books as “pornography” to make them inaccessible to readers of all ages. However, book banning is only part of the genre’s continued fight for survival.

Those who oppose YA literature are definitely part of the problem, but those who support it may also be unintentionally harming it. So many adults are reading, publicly reviewing, and commenting on YA literature that YA books are now tailored to adults instead of teens. There’s also the issue of adult books mislabeled as YA literature, and vice versa. The problem isn’t that kids can’t read or handle any content deemed “adult.” It’s that adults and young readers are two completely separate markets, and the needs and interests of each ought to be evaluated separately. Additionally, price hikes in books make YA literature inaccessible to their target audience.

The problem with adults reading YA lit

Adult consumption of YA literature is starting to become a problem, but not for the reasons you might think. YA literature can be enjoyed by all ages, and there’s nothing wrong with reading books that are written for audiences outside your age range. The problem arises when publishers start trying to market books meant for 12 to 18-year-olds to adults. Ashley, the Booktuber behind Bookish Realm, posits that YA books are being “aged up” to continue to appeal to the growing adult audience. A YA book could feature young characters who behave more like adults. These characters could also parallel teens from the ’80s and ’90s instead of contemporary teens, to provide nostalgia for adult readers. This could also mean content that is more mature and/or above the intended audience’s reading levels.

Again, it doesn’t mean that YA literature is “too adult” and inappropriate for kids. However, it does mean that it’s appealing more to ages 16 and above. The fact is, what interests an adult is not what interests a child 12-15. While readers ages 16+ can enjoy a book more geared towards adults, one can’t forget that kids as young as 12 are included in YA’s target audience. Ashley discussed how hard it is to recommend books for those 12-15, because a lot of YA books are more focused on romance and adult themes. These books might be too advanced or mature for a young reader just growing out of elementary school books.

Aging up YA books to make them appeal to adults often means those at the younger end of the YA age range get left out. A 12-year-old doesn’t just go from reading Judy Moody to reading what interests a 30-year-old overnight. If YA books aren’t able to serve as the transition from children’s books to adult books, it can create a gap in which certain young readers don’t have enough books that are specifically tailored to them.

The effect of adult readers on YA lit

The proliferation of adult YA fans may also be exacerbating another existing issue—pricing. As Twitter user @zlikeinzorro pointed out, YA books have greatly increased in price. While some consumers can remember a time when YA books cost $9.99 for a hardcover (and as low as $5 for a paperback), today a YA paperback can cost as much as $16, while a hardcover can reach $24. It’s a hefty expense for a teen making minimum wage at a part-time job, or a child relying wholly on allowances. Young readers are being priced out of book purchasing and there are many reasons why, including inflation and the rising cost of paper. However, the price may also reflect that these books are being marketed to adults and focusing on what adults can afford, rather than on what teens can afford.

There are also other ways in which adults are influencing the YA genre. Today, many of the BookTubers, BookTok creators, and Goodreads users who are reviewing, rating, and providing feedback on YA literature are adults. Hence, much of the online feedback that publishers are utilizing is coming from adults instead of from the books’ intended audiences. Adults who leave feedback and make suggestions about how YA literature could appeal more to them are not doing so maliciously. Many think they’re helping save YA literature by raising sales and making the books more appealing to adults. A Twitter thread sees the founder of Daphne Press suggesting that YA authors write more science fiction, fantasy, and speculative fiction (SFF) instead of contemporary fiction for just that purpose.

While she makes a good point that widening the audience for YA books can result in more profit, she’s missing the underlying problem: teens aren’t buying YA literature. However, instead of focusing on why they’re not buying it and how to make it more affordable, accessible, and interesting to teens, the industry is trying to use adult interest to bolster sales. This may temporarily increase sales, but eventually there’s going to be no separation between YA and adult literature. YA literature was created specifically to help young readers to transition from children’s to adult books, and to give them resources that tackle topics that they may be dealing with in real life. Making YA literature more appealing to adults undermines the very reason why this group became its own market in the first place.

How mismarketing books impacts authors

As the separation between YA and adult books becomes less apparent, many authors are having their books erroneously marketed as YA novels or vice versa. Fonda Lee, the author of the Green Bone saga, expressed frustration at how many times her books were referred to as YA.

Meanwhile, she perfectly explained why the frustration has nothing to do with trying to “police” what teens read.

The thing is, most writers write with a specific target audience in mind. They put lots of thought and work into ensuring that their book appeals to the audience it was meant for. Doing this successfully can strengthen the impact and reception of the writing, but not if a written work is suddenly advertised to an entirely different audience. Target audiences are important for both authors and readers. Acknowledging the differences ensures that authors have a specific demographic to write for, and that each age group of readers has a wide selection of books tailored to their needs and interests.

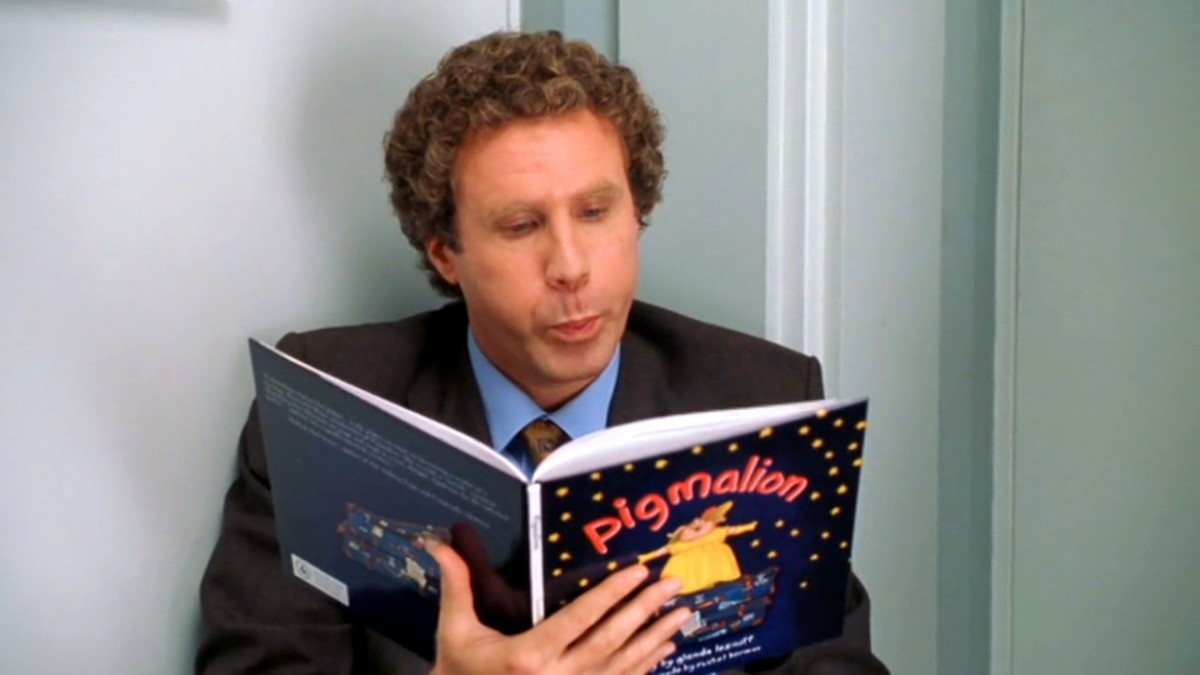

(featured image: New Line Cinema)

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com