Pretty Much Everything Movies Have Told You About Corsets Is Wrong

Sorry, Brigerton

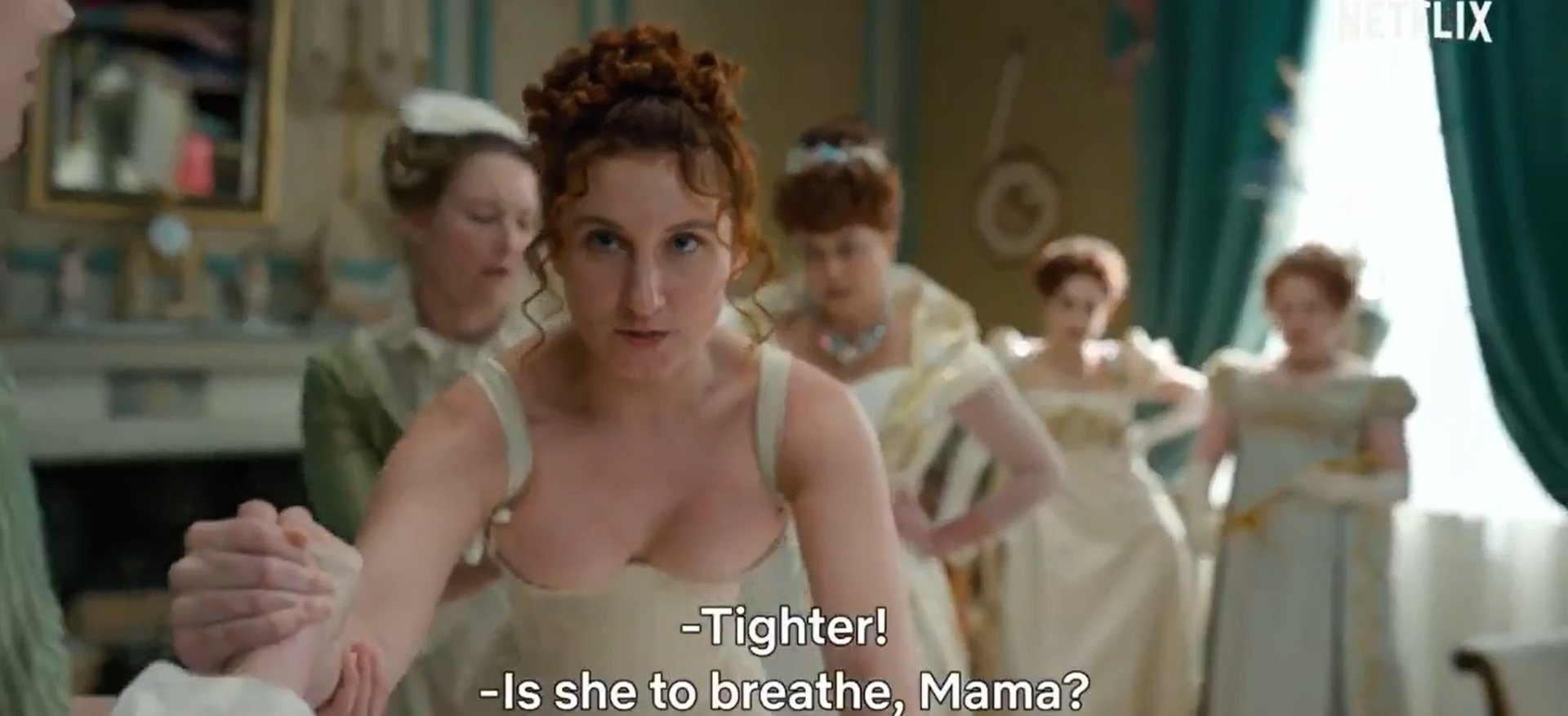

Netflix released Bridgerton on Christmas Day, and while it’s not meant to be a strictly historical portrayal of Regency life, the big inaccuracy that caught my eye just from the trailer was the costumes. Not only did the show seem to be using costumes from different centuries, with typical Regency looks from around the late eighteen-teens mashed against much earlier looks from forty years prior, but they also did the thing I hate in period movies and made a joke about a woman not being able to breathe in a corset.

You see, pretty much everything you think you know about corsets, bodices, stays, and period undergarments, in general, is probably wrong.

First off, let’s get some terminology out of the way because it can get very messy, even for dress historians, thanks to the way language evolves. Just ask Abby Cox, who did a really comprehensive video on her YouTube channel about the distinction last month, and whose content on corsets and stays, in general, is amazing. “Corsets” as a term for a boned and laced support garment is a relatively new term, according to Cox. The word corset didn’t quite take off until maybe the Victorian era, and usually meant a support garment that wasn’t boned.

Before this most such garments were called “stays,” or “bodies” in an earlier era. (You can see how “bodies” possibly morphed into the word “bodice.”) What we think of as a “corset,” with tight lacing meant to constrict the waist specifically, reached peak popularity in the Victorian era. But before that, undergarments were actually far more comfortable than what movies would have us believe.

Let’s discuss the Rocco/Georgian period first. The typical undergarment of this era, usually stays, varied, like all clothes do, but the emphasis was on conical torso shape, a flat front, and not necessarily on a teeny-tiny waist. The illusion of a smaller waist was created by large skirts, padding, and hoop structure, and but the purpose of a pair of stays, or bodies, was as more bust support and posture than it was to make someone appear thinner. Here’s an example from the Fashion Museum in Bath:

Stays and corsets of the ers would often be embellished and visible under a dress. And they were also highly adjustable for those days when you were a bit more bloated, or for pregnancy. But these were what most women wore, day-to-day; what women worked and lived in. They supported busts and made clothes look better over them. They weren’t the torture devices we like to think of when it comes to ye olde days.

This was even more true of undergarments in the Empire and Regency eras. The fashions of this era were crafted in a direct counterpoint to the frilly, structured, over-the-top fashion of the pre-revolutionary era and a response to the supposed decadence of things like the French monarchy. Women’s clothes of the era were meant to emphasize a more natural silhouette and soft curves. This not only makes the mixing of style in Bridgerton even more confusing, but it also reminds us that restrictive, waist-cinching corsets just … were not a thing in the era of Austen. Waistlines were very high, right below the bust (we call that an empire waist for a reason!) and so there was no need for tummy flattening or waist reduction.

That means that the scene from the trailers and seen in the top image would never have happened!

Emma featured extremely accurate regency costuming.

That’s not to say there were no undergarments, but they were more concerned with providing structure and support for the bust, which was emphasized. It wasn’t until decades later that corsets cam back in style, and even then, the Victorian “wasp waist” was even later and not nearly as prevalent a fashion as you might think. Most fashionable silhouettes were achieved through a combination of corsetry, padding, and tailoring. And even so, that fashionable silhouette was always evolving.

In fact, what really defines our ideas about corsets and other such garments isn’t the body standards of the past, but those of the present. While it’s true that corsets were restrictive in many eras, that wasn’t always the case. We see it that way because that’s what beauty standards are doing to women right now.

The idea that stays, bodies, and corsets existed to squeeze women into an ideal thin shape is not really accurate, because the veneration of extreme thinness as the female ideal body is something that’s in many ways a modern idea. The “ideal” body has varied tremendously over the years, and when we assume corsets of ages past only existed to make people look skinny, we’re placing our modern ideal onto the garments.

In movies and shows like Bridgerton or Pirates of the Caribbean or Ever After filmmakers use corsetry inaccurately as shorthand for female oppression and unfair body standards. But corsets so tight you couldn’t breathe simply were not the standard in the eras in which these films were set. And it’s even more offensive because often the women getting forced into these evil, restrive garments are already super skinny. That’s just lazy and it should stop.

Screenwriters and costume designers often fall back on our ideas and stereotypes about the past, instead of doing their research. They’ve seen a dozen movies going back to Gone With The Wind where women were forcefully laced into corsets to meet some barbaric beauty standard so they just throw it in their show too. But real history is far more complex and the history of fashion is as complex as the history of humanity.

Hollywood can’t pat themselves for being so evolved that we don’t wear corsets anymore while it still promotes all but unattainable body images. Just like with so many other things, we can’t excuse the present by demonizing the past as a means of saying we’ve improved. We need to be honest about both and give ourselves so real breathing room.

(image: Netflix)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com