Does Famine Breed More Girl Babies?

Consider the Following

The Trivers-Willard hypothesis is a theory that states that in species that don’t mate in pairs but polygynously (males mate with many females), evolutionary pressure will have created reproductive biology that responds to periods of easy living and periods of hard living by actually skewing the normal 50% chance of producing offspring of one sex or the other. In good times, things would skew towards male offspring, because the easier it is to raise a healthy kid, the better chance your genes have of becoming that dominant male that gets to reproduce with lots of females. In bad times, however, things would skew towards the female. If raising the best male is a longer shot, at least a healthy female will get to reproduce with the healthier males.

Both ground squirrels and red deer populations correlate with the theory, and now, at least according to a study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society, humans do too well. And yes, we’re generally considered to have descended from polygynous apes.

Understandably, proper census data during widespread famines can be difficult to come by (perhaps fortunately), but the Dutch famine that occurred during the winter of 1944-45 and the 1942 Leningrad Seige have been notable examples. Attempts to find gender skew in birth populations months after the famines have been entirely inconclusive, according to Discover. However, according to the publishers of the study, this is because those famines lasted only about half a year at most.

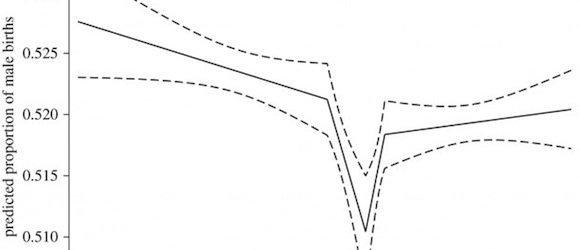

Their study focuses instead on data culled from the Great Chinese Famine, generally acknowledged to be mostly the fault of policies laid down by Mao’s Great Leap Forward, which lasted three entire years, killing 15-45 million people with malnutrition. Discover showcases this graph of the proportion of male babies born during the period. The proportion dips sharply around 1961, three years after the beginning of the famine, and then slowly rises.

As Discover says, this only shows correlation, not causation.

There could confounding social reasons, especially as the data is based on a retrospective survey of 300,000 women, but it seems that the Chinese bias toward having sons is more likely to drive the ratio in the other direction. (China’s one-child policy was not enacted until 1978, so it has no bearing on the famine data either.)

The study’s author has announced their intentions to refine the study by looking at statistics from different areas of China, that were affected by the famine at different times of the three years. Needless to say, we do not recommend this as a method of trying to have a daughter.

Read the whole article at Discover.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com