Long Live Fandom: Fandom Isn’t Broken

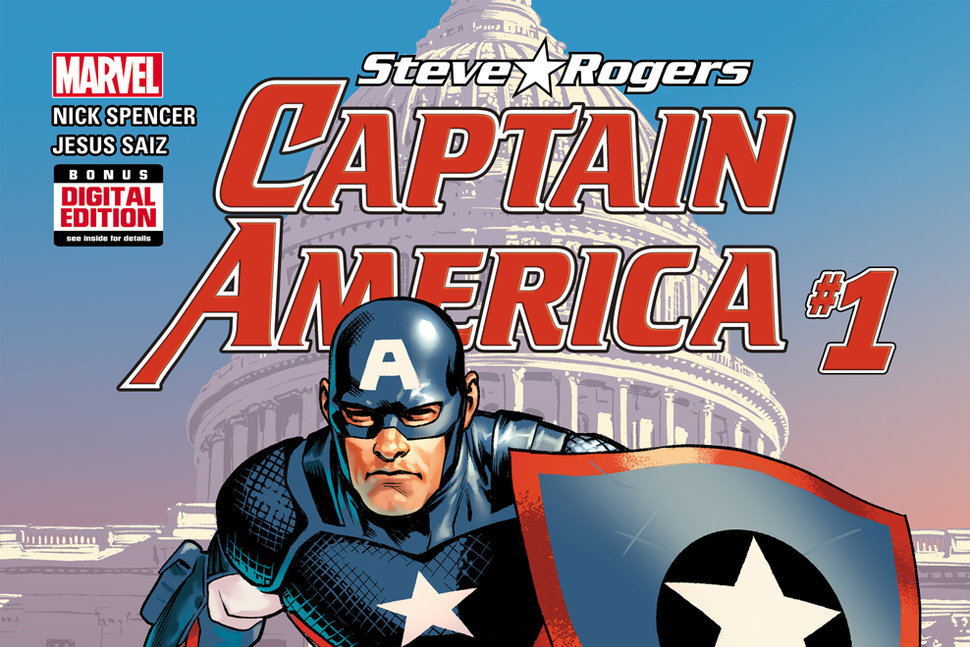

Spoilers for Captain America #1 to follow.

Last week, critic Devin Faraci wrote a piece proclaiming “fandom is broken.” From his perspective, fandom has become too demanding—too entitled to get exactly what they want. Faraci likens fans on the internet to Annie Wilkes in Misery, the “patron saint of fandom.” He wrongly lumped together comics fans upset about Steve Rogers being hydra all this time and the misogynists behind the targeted harassment of Gamergate, but the big thing Mr. Faraci misses, even though he issued a caveat later that he agrees with fans calling for diversity in media, is that fandom is much more than yelling in Caps Lock over twitter. Fandom isn’t broken; it’s what’s fixing things.

First off, let me admit that I’m writing from the trenches of the fandom wars. I’ve seen the bad stuff. I’ve received the anonymous hate and the Twitter harassment. I get as annoyed as anyone with the entitlement my fellow fans feel sometimes to actors’ lives, creators’ choices, and others’ agreement. In many ways, I agree with Faraci in that fans do sometimes miss the point that drama equals people being sad, and characters suffering and dying. Personally, if I have to read one more “stop hurting [insert character here] 2k16” tweet, I’m going to have to get my screaming cup. No matter how progressive or inventive, mainstream media—and, well, western storytelling—has certain constraints.

But fandom is there for us to fix that. I didn’t spend last weekend reading 125,000 words of fanfic about my Dean and Cas renovating houses and petting cats because I want that on my television, but because I love the characters the original created, and I want see them in different situations that will never happen on Supernatural … mostly being happy. That doesn’t make me foolish or childish or unappreciative of canon, and that doesn’t invalidate the fact that I think it would be both plausible and awesome for them get together on the show. We come to a fandom because we fall in love with a world, with characters, and with a great story, and when we fans get critical, it’s usually not that we want the artists to cater to exactly what we want, but because we know they can do better since they already have done so well.

We fans love our characters, and we want to protect them from simple bad writing. Why were fans annoyed when Agent 13 was shoehorned in as a love interest in Civil War? Why is our reaction usually to groan rather than cry when Game of Thrones kills off yet another character? Not because we’re needy, but because we’re bored. Heteronormativity and shocking deaths, among other tired tropes, have been done, well, to death. The Internet has made critics of us all, but that’s not a bad thing, because now, we have a voice to ask—and, yes, sometimes demand—change. Creators who stand in a digital arena strewn with dead lesbians that were secretly Hydra all along, asking, “Are you not entertained!?” shouldn’t be surprised anymore when the answer is no.

That’s why fandom is important, because it calls attention (albeit sometimes in a loud and annoying way) to media’s failures and asks them to improve. Media doesn’t exist in a vacuum, though I think many creators unhappy with demanding fans wish it did. No one likes being told that people don’t like their work, but if I order steak at a restaurant and it comes out undercooked and badly seasoned, I have a right to tell the chef they messed up. No one expects you to eat a meal you don’t enjoy because it expresses a single person’s artistic vision. Fandom refuses to accept offensive or bad stories for the same reason. Refusing to “cater to fans” is, in some ways, just creators refusing to acknowledge their mistakes, or even their own limited creativity or lack of bravery. This is true especially when those mistakes resonate with very important, very real issues for fans.

Fandom (real fandom, not the toxic shouting matches that bog us down) can be an amazing place that seeks to celebrate and educate about diversity. We learn about sexuality and privilege and literature and so much more by interacting with others in a way only fans can. Fandom can be a sanctuary for marginalized communities, especially women and members of the LGBTQIA community to gather, explore and celebrate our identities. It shouldn’t be shocking that fans would also like to see our identities honored and validated by the actual media that brought us together, but it’s a very tough fight. The female Ghostbusters is exciting, but the reaction of angry male fans to that is dismaying. We got #GiveElsaAGirlfiend trending, but it’s in reaction to the fact being a gay lady on a screen today equates to a death sentence. We’re still rightfully annoyed that it’s considered more plausible that a character was secretly a Nazi all along than they could be bisexual. These things break a lot of fans’ hearts, but thankfully, fandom is there to pick them back up.

Fandom can help make media more inclusive, both in terms of who’s creating it and the identities represented in it. It can also help actual fans grow and heal. Fandom can save lives. We do it through creating community, through characters and actors giving people in the darkest point in their life hope. The Supernatural fandom is a shining beacon of this, whether it’s through Misha Collins’ Random Acts charity spreading kindness all over the world with the help of fans or Jared Padalecki coming forward with his own struggles with depression and raising awareness through his “Always Keep Fighting” campaign. Sure, fans can be jerks on the Internet—so can everybody—but Supernatural fans also came together to help Collins and co-star Jensen Ackles create an Internet-based crisis support network for fans to help each other cope with harassment, depression, and self-harm.

It’s very easy to focus on the negative things when the loudest voices are often annoying, petty, and lack understanding. That’s not something that’s broken in fandom, though; it’s a more general flaw in human nature. What I implore creators, critics, and fans in general to do when they see “entitled” behavior is to look a little closer. Recognize that for every one jerk going overboard, there are a hundred more probably making a very valid point. Many of us do want to see the mainstream media be a bit more like fandom—more diverse and more creative—but that’s not a bad thing.

Jessica Mason is a writer and lawyer living in Portland, Oregon. More of her writing can be found at www.fan-girling.com, and follow her on Twitter at @FangirlingJess.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com