FiveThirtyEight Turns the Lidless Eye of Data Crunching to Gender Disparity in Superhero Comics Characters

Great Hera!

They’re also predicting that Lex Luthor will win his bid for president of the United States.

Nobody crunches numbers like FiveThirtyEight, except maybe Randall Monroe and Tim Hanley, the latter of whom is, naturally, referenced in Walt Hickey’s breakdown on FiveThirtyEight.com. Hanley has been crunching the numbers on the gender make up of the folks who work on Marvel and DC comics for years, but FiveThirtyEight wanted to take a slightly different tack by looking at the characters who make up those comics in the first place.

Hickey’s database was that of any good nerd: the fan-curated DC and Marvel wikia projects, which gave him access to lists of characters who had ever appeared in a given comics issue, as well as their gender and sexuality, secret identity, alignment (whether they were a hero, a villain, or neutral), their date of first appearance, and their total number of appearances. Speaking as a regular user of those wikia projects (thanks to a hard drive failure, I have a LOT of back issues to catalog in Delicious Library, believe me), I wonder about the overall accuracy of those total appearance numbers. I’m sure they’re broadly accurate, but more often than not unless a given comics issue was part of a popular run, its entry can lack any information beyond creator names and release date, much less which characters appeared in it.

Of course, there’s a whole ‘nother discussion to be had on why we so often focus on the Big Two when we want to talk about female characters in comics. Which is not to say that the focus is unfounded, but simply that it’s useful to examine the reasons, if only so that we don’t forget to acknowledge the existence of a vibrant American comics industry outside of those two companies. If I had to nail down the biggest reason: I think “superhero comics are our most universal modern American mythology” is a fairly solid position to take, and, in that context, examining who that mythology is designed to appeal to is vitally important.

But I digress: numbers were crunched. For the real nerds reading this, in order to cut down on duplicates due to different versions of characters, Hickey’s data only includes characters from the longest running continuities at DC and Marvel, DC’s New Earth universe and Marvel’s Earth-616 universe. The data also begins in 1961, the year that Marvel Comics began publishing under their current name.

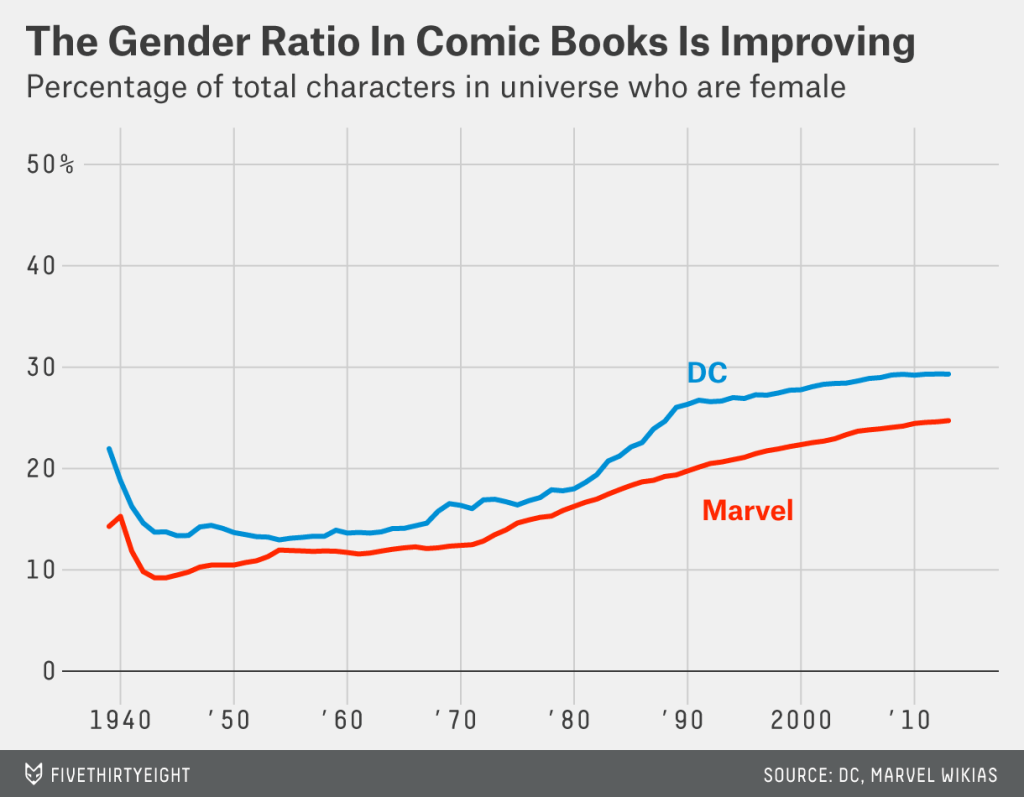

Women were substantially underrepresented among characters with at least one appearance. Among the characters for which we have gender data, females made up only 29.3 percent of the DC character list and 24.7 percent of the Marvel roster…

The same trend bears out when we look at characters with higher appearance counts. When we zero in on the 2,415 DC and 3,342 Marvel characters with gender data who appear at least 10 times — the set of characters that probably gives the most consistent view of what we see on the page — female characters make up only 30.9 percent of the DC universe and 30.6 percent of the Marvel universe…

Of characters with gender data and 100 or more appearances (294 DC characters and 414 Marvel characters), only 29.0 percent of DC’s are female, and a similar 31.1 percent of the Marvel crowd is…

Hickey attributes Marvel’s bigger gap between female characters with “>1 appearances” and “>10 appearances” to a huge disparity in the gender of one-off villains. 44% of Marvel characters who appeared less than 10 times are bad guys, and Marvel’s bad guys are 80% male.

In both DC and Marvel, women were of neutral allegiance at a higher rate than men. Men were also more likely to be bad in each universe — in fact, bad-aligned men alone outnumbered all women combined. In other words, there’s something of a paucity of female villains.

This would certainly bears out my own anecdotal experience as part of a gender-swapped villains cosplay group a few years ago: it was way more difficult to find enough female villains for the guys to redesign. Hickey noted that overall, gender parity is improving over time at the Big Two (see this article’s top pic), but of new characters created every year since the 1980’s, less than 50% are female, with a peak in the early ’00s of 40-45% female. The pace of change is somewhat glacial (again, see this article’s top pic). You can read all of Hickey’s commentary and findings at the full article on FiveThirtyEight.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com