Four Quarks Good, Two Quarks Bad: Scientists Detect New Kind of Subatomic Particle

Particle accelerators in Japan and China may have turned up evidence of a never-before-suspected subatomic particle.

Researchers at two different particle accelerators have discovered what looks like evidence of the existence of particles composed of four quarks. Don’t know what that means? Don’t worry, the scientists involved aren’t quite sure what to think yet, either. They don’t even know if the results are truly new particles of just misleading blips in mountains of data. One thing is for sure, though — if you thought we were done talking about particle physics once we found the Higgs boson, guess again.

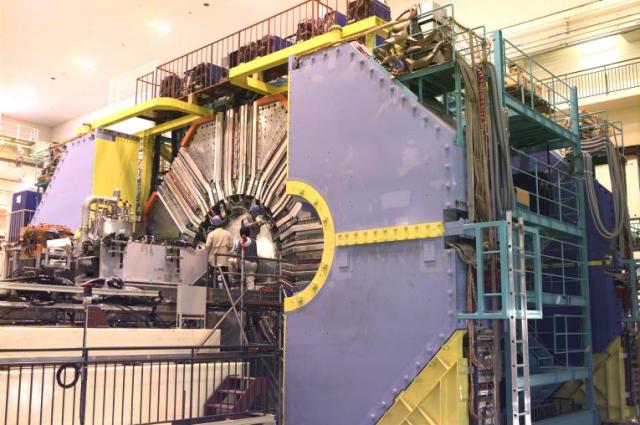

The BESIII Collaboration at the Electron Positron Collider in Beijing, China, and the Belle Collaboration at the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization in Tsukuba, Japan have both conducted experiments that yielded signs of a particle tentatively called Zc(3900) which appears to be made up of four quarks and has an electric charge. Quarks — the subatomic particles that make up the building blocks of matter — normally combine in threes to make hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, or in twos to make particles called mesons. Combinations of four or more have never been detected before, meaning that if these findings are borne out, pretty amazing new avenues of research in particle physics could be opening in short order.

Quarks, which make up most of what we think of as matter, have a multitude of different combinations and interactions and can be quite strange. No, literally — strangeness is an actual, quantifiable property of quarks. That’s how weird they are already, and these new findings suggest they could be about to get a lot weirder. The existence of four-quark particles means a major expansion to the number of combinations that can be made with the six ‘flavors’ of quarks: up, down, strange, charm, top, and bottom, and their six antiparticles.

Both teams that made the observations use particle accelerators that collide electrons with positrons, their antiparticle counterpart, and analyze the results, which only exist for fractions of moments before decaying. Between the two teams, they have identified 466 events that contained the four-quark particle in the debris of the collisions, and they expect that physicists at other electron-positron accelerators will find the same results if they go through their records. They were trying to observe mesons made of charm quarks, which are known as “charmonium”, but then found signs of the Zc(3900) particle. And we should count ourselves lucky the physicists didn’t try to give it an official name, given that the charmonium meson they were studying has been stuck with the name ‘J/Ψ meson’ for forty years because one team of scientists called it J and the other called it Ψ.

There are two possibilities as to what the theory on the new particle is: it might be the real deal— an entirely new formation of quarks, but there is a chance it could be a bunched-up pair of mesons. However, the latter, more disappointing possibility is considered less likely due to the way the particle was observed to decay. In either case, the next step is for independent teams to do their own tests to confirm or deny the current results two teams’ results.

(via Ars Technica, image via Karlsruhe Institute of Technology)

- Particle accelerators explained in cartoon form

- Large Hadron Collider researchers may have created new state of matter

- An explanation of the Big Bang that takes under four minutes

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com