Stop Whining, Nice Guys: You’ll Do Better in the Long Run

Also, maybe we should all start using game theory to make decisions?

The field of game theory, and specifically an experiment known as the prisoner’s dilemma, has been used in the past to show that being selfish is a surefire way to do the best in the long run. But a new study suggests that might not be the case, showing in computer simulations that cooperation is actually the best overall evolutionary tactic.

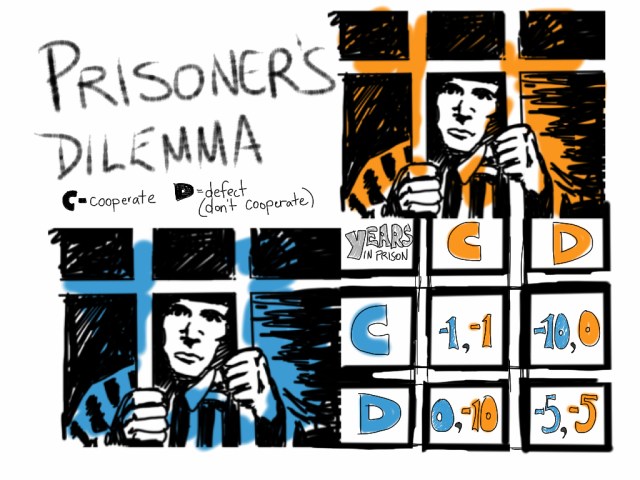

For those of you who aren’t familiar, the prisoner’s dilemma is modeled as follows: two people criminals are arrested and placed in solitary confinement, unable to communicate with each other. The police, without enough evidence to convict the pair for a serious crime, intend to imprison them both for one year, then approach each criminal individually and offer them a spectacularly Faustian deal: testify against their partner to go free, condemning the partner to ten years in jail. If both men betray their partners, they each face a five-year sentence.

To sum up: both refuse to snitch on each other, and they stay in prison for one year. Both betray the other, and they stay in prison for five years. One rats out his partner, and goes free while the partner stays in prison for ten years.

Scientists across a number of fields have used this model to study cooperation under the threat of limited resources, exploring subjects from biology to economics to the Cold War. A little over a year ago, two physicists came up with a guaranteed way for selfish players to win over their cooperative partners, called zero determinant (ZD). But molecular genetics and microbiology researchers Christoph Adami and Arend Hintze of Michigan State University were unconvinced.

They created a computer program to to run thousands upon thousands of games, using the ZD. The results, published this week in the journal Nature Communications, suggest ZD works sometimes, but you have to have extra information to make certain. That means it would not have worked as an evolutionary strategy, where unknown factors are prevalent. Those who use ZD can only use it against those who don’t, meaning that even if they somehow only encountered cooperative opponents until all of the “nice guys” were weeded out, the various ZD populations that survived would have to begin cooperating.

Further, the study shows that regardless of the strategy used, communication and information are essential components of cooperation, which game theory often discounts for simplicity’s sake.

Long story short: doesn’t matter how tough you and your species were once upon a time, you need communication and cooperation to evolve and survive.

(via Phys.org, image via Giulia Forsyth)

- There’s science behind why we lose at games

- It’s actually better to be ugly on OKCupid than cute

- Artificial intelligence is on the rise, and that might be a good thing

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com