Were You Hoping Glass Would Be M. Night Shyamalan’s Return to Form? Well, I’m Sorry.

Is zero stars an option?

**Spoilers ahead for Unbreakable and Split, but none for Glass.**

In 2000, Unbreakable was a formative movie for my teenage self. It was the first DVD I ever bought with my own money. I’ve watched it periodically over the years and always thought it held up, or at least never made me lose my nostalgic love for it. So at the very end of 2016’s Split, when Bruce Willis appeared, turning that movie into an installment of an extended Unbreakable universe we didn’t know existed, it was an exciting moment.

All of this is to say that I went into Glass, the third installment in the so-called “Eastrail 177 Trilogy,” with high hopes, but also a lot of love and generosity. Since watching the movie, I’ve been trying to imagine if there’s another mentality someone could walk in with—lower hopes or expectations, or less of an opinion about the original film, or maybe not having seen it at all—that could make this movie any better.

And I really don’t think there is. This movie is just plain bad.

Glass is about 90% exposition, but much of it isn’t useful exposition, and if you haven’t seen both Unbreakable and Split fairly recently, you’ll likely be lost right from the start. So briefly (and feel free to skip ahead if you don’t need a refresher), Unbreakable centered on David Dunn (Bruce Willis), a mild mannered security guard who winds up the lone survivor of a tragic train wreck. A man named Elijah Price, along with David’s young son Joseph, convinces Dunn that he has superhuman abilities and is nearly indestructible, save for a weakness of water.

Elijah, meanwhile, was born with a condition that makes his bones extremely breakable. One might even say they’re like … glass. (Look, I know that’s not even funny, but it’s impossible to write about these movies without giving in to terrible lazy puns.) He’s also had a lifelong obsession with comic books and superheroes, and always believed that if there could be someone like him, who’s unusually fragile, there must be someone like David, who’s superhumanly strong.

But by the laws of comic book structure, that also means that if David is a superhero, Elijah must be a supervillain. He, it turns out, caused that train wreck, along with tons of other accidents, in order to find someone like David.

In Split, we meet Kevin, who shares his body with 23 other separate personalities. Many of these personalities—collectively dubbed “The Horde”—worship one called “The Beast,” who has superhuman strength and can scale walls. He also wants to cleanse the world of those who are “impure” and “untouched” by suffering. Kevin abducts a group of teenage girls, including Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy), who is spared by The Beast when he sees the scars on her body, left by her sexually abusive uncle.

So back to Glass. When this movie opens, The Beast has never been captured and has abducted another group of teen girls. David has been taking care of small-time criminals with the help of Joseph, as the two now run a home security store together, allowing them access to surveillance equipment. When David tracks down The Horde’s lair, he and The Beast face off but are quickly arrested together by Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson), a psychiatrist who specializes in treating people she believes to have delusions of grandeur—normal people who have convinced themselves they have super powers.

If it seems strange that you’ve just read 500 words and we’ve barely gotten to the movie itself, well, that’s pretty much in line with how Glass is structured. I mentioned that the exposition in this movie is constant but not useful. That’s because the script dedicates an unreasonably excessive amount of time basically explaining what comic books are, how their story structure works, and making sure you understand the parallels we’re seeing in the characters, as well as lecturing the audience on the morality of comic books.

Paulson’s Dr. Staple repeatedly tells us how ridiculous comic books are, how people that go to comic book conventions are “obsessed” and how they’ve “lost their perspective.” Both Joseph and Casey turn to what is apparently the only comic book store in Philadelphia to learn lessons from comics that they can apply to their current situation.

Joseph wants to crack the Beast’s backstory weakness, while Casey’s role in this movie is to serve as Kevin/The Horde’s protector, as she is able to wield the “power of true affection,” which Dr. Staple calls akin to something “supernatural.” Remember, this is the same Casey whose sexual assault was ultimately implied to be worth it in Split because it meant she was spared by The Beast. There’s so much to unpack here that it requires its own article, so we’ll come back to this later, when we can dive into some spoilery territory.

Also, their comic store revelations are sometimes highlighted by actual neon signs. I cannot remember ever seeing a movie that trusted its audience less.

With better editing, both in script and film, there could have been a fun, if obvious, montage of realizations and comic book tropes here. Instead, we’re repeatedly shown and told, and told again, obvious points from comic lore—Heroes have origin stories! Some are tragic! Some heroes are monsters! And none of it has any payoff whatsoever because at this point, there’s no one watching Glass that doesn’t know these things.

A lot of this exposition is similar to the structure of Unbreakable, as Elijah turned to comic books for breakthroughs in his theories about David and real-life supers. So what’s different now? Well, while M. Night Shyamalan has sold this movie on being 19 years in the making, it’s clear that during that time, he didn’t update his view of comics in the slightest.

In 2000, we were still in a pre-blockbuster comic book movie world. The first Toby Maguire Spider-Man movie was still a year and a half away. The comics Elijah turned to were Golden Age ones, and they told the story that fit his vision. But here, 19 years later, our collective view of comics has changed, as has their structure and their purpose as a medium. There is about an hour of this movie where nothing at all happens because it’s busy telling us how comic books work and how amazed we should be by the parallels between books and reality.

In Unbreakable, that was a fascinating and exciting dive into material that the majority of the audience probably wasn’t overly familiar with, but Glass devotes itself to lecturing us that superheroes are real and that there are practical concerns to be considered, which is immediately a tired idea and makes one wonder if Shyamalan has even read a comic book written after 2001—or even, maybe, 1960.

Shyamalan spends the entirety of the movie making sure the audience understands the importance of origin stories, hero/villain foils, inciting incidents, final showdowns, and so many other incredibly basic plot devices. It’s like if Stephen King spent the entirety of The Shining make sure the audience knew that writers can be lonely and winking incessantly that ghosts can be real. It’s exhausting and unnecessary and leaves no time for actual plot.

The best part of Glass, as with many of Shyamalan’s movies before it, is its incredible cast, but even these actors can’t save the movie because, at the very least, they’re not in a position to be able to. Bruce Willis appears to have been shot out pretty quickly, with a stand-in and stunt double in a green trench likely doing the heft of the work here, hours-wise. His character isn’t really allowed any sort of development at all.

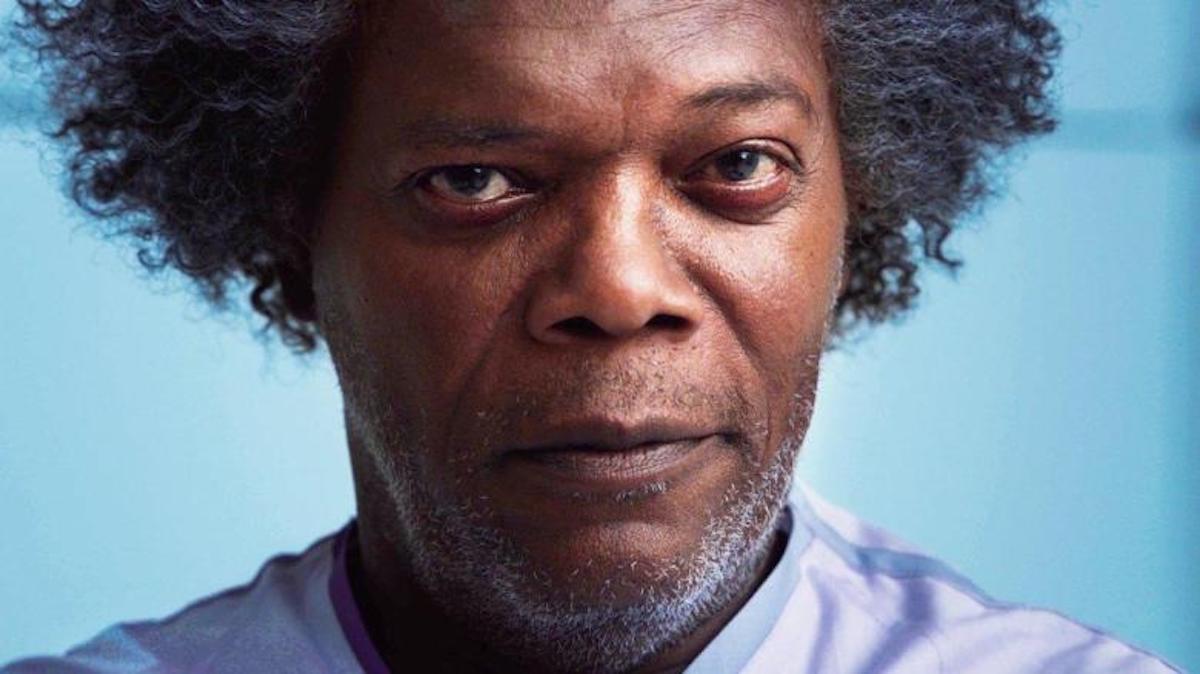

If you couldn’t quite tell how Samuel L. Jackson fit into this movie from the trailers, that’s because the creators don’t know, either. He doesn’t really do anything until well past the halfway point. Anya Taylor-Joy is reduced to a trope, and I’m amazed that a movie could make me dislike Sarah Paulson, something that should be considered an actual crime. But her character is so aggressively one-dimensional that she’s almost exhausting to watch.

I wish I could at least recommend Glass as a guilty pleasure or a hate-watch, maybe with some fun comic book trope drinking game attached, but I can’t. It’s just genuinely bad and should never have been made. I left this movie with an actual headache and a visible crease in my brow from cringing for two hours straight. If you love Unbreakable, stay away. If you hate it, or if you nothing it, stay away. Just … stay away.

(image: Universal Pictures/Blumhouse)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com