The Dreamer and the Dream: Looking at the Sexism That’s Glossed-Over in My Fave Ep of Deep Space Nine

“Far Beyond the Stars” is my all-time favorite episode of Deep Space Nine, and as my wife got to it last night during her umpteenth rewatch of the series, I watched it with her. All the same moments got me: Benny Russell getting his DS9 story rejected, Jimmy mournfully laughing at the idea of “Negros in space,” Russell’s impassioned speech about how “you can’t kill an idea!” However, something new stood out to me in a way it never had before.

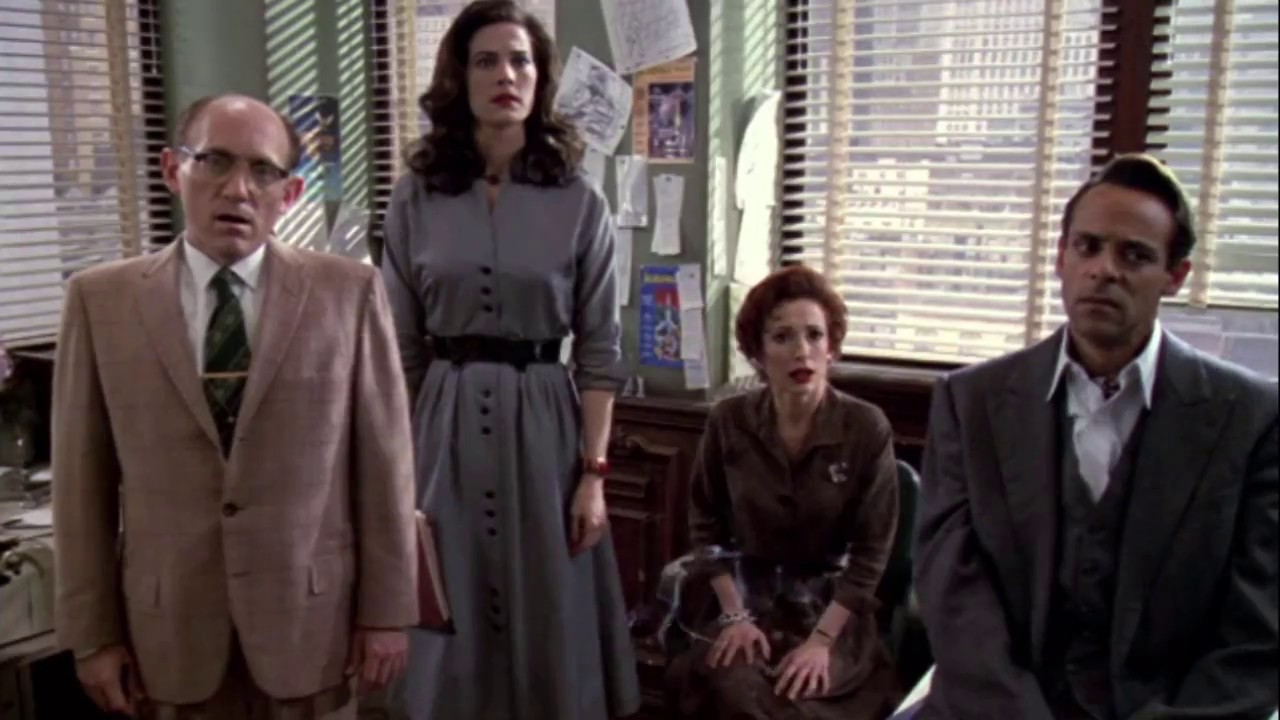

For those who are unfamiliar, “Far Beyond the Stars” has Commander Sisko (Avery Brooks) under the influence of a vision sent him by the Prophets. Suddenly, he is a man named Benny Russell, a sci-fi writer in 1950s New York City who works for a sci-fi magazine called Incredible Tales fighting to get a story called Deep Space Nine, featuring a black captain on a space station, published at a time when the average pulp sci-fi reader wasn’t ready for black authors.

All of the Deep Space Nine regulars have human versions of themselves in the episode, including Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor), who in this vision is Kay Eaton, another writer at the magazine who uses the pseudonym K.C. Hunter. Why? Because the average pulp sci-fi readers at the time also weren’t ready for female authors either.

It’s awesome that both racism and sexism are brought up in this episode. However, what I noticed is that, while racism is front and center, dealt with head-in in a beautiful allegory, sexism is brought up only to be shrugged off and promptly forgotten. When René Auberjonois’ magazine editor, Douglas Pabst, comes in to announce that their publisher wants to print a photo of the staff in the magazine, both Kay and Benny are advised to “sleep late” on the day the photo is taken, because they weren’t allowed to be in it and show their faces to the world.

However, it’s Kay that first has to deal with the fact that she wouldn’t be needed, saying “Of course I can. God forbid the public ever finds out that K.C. Hunter is a woman.” But that’s all she says on the matter. She’s upset, but she’s resigned. This is just how it is, and she absolutely expected it.

Benny expects it, too, but the script offers the opportunity for a fight in his defense. He asks, “I suppose I’m sleeping in late, too?” Then Pabst proceeds to apologize, making excuses for the fact that he’s too cowardly to stand up for Benny. The thing is, Pabst doesn’t feel the need to apologize to Kay, or explain his position in the same way.

When Herbert Rossoff (Armin Shimerman), a fellow writer, brings up injustice, it’s when Benny is told to sleep in. He tacks “woman writer” onto his spiel, but the thing he’s really taking issue with is Benny being maligned because of his race. What’s more, in an attempt to further explain himself, Pabst says that Benny can’t be in the photo, because “The average reader is not going to spend his hard earned cash on stories written by negros.” His hard earned cash. Because only men care about or read sci-fi. Never mind that his own new secretary, Darlene (Terry Farrell), is a huge sci-fi fan.

Oh, and of the five authors that Benny names to prove how acceptable black writers are, only one—Zora Neale Hurston—is a woman.

Now, obviously race is the primary focus of the episode, and it’s understandable that they might not have necessarily wanted to talk about gender issues at the same time, because it might “complicate” things. The thing is, these things are complicated, and that’s not more clear than when we look at the one prominent woman of color in the episode, Benny’s girlfriend Cassie.

She is a waitress at a popular diner, and when we meet her, she tells Benny that she has great news: the owner of the diner would be willing to sell the diner to her and Benny. Cassie sees this not only as a huge opportunity, but as the answer to the fact that Benny doesn’t pull in much money as a writer. So, she’s extremely disappointed when Benny shoots down the idea, telling her that he’s a writer, and that writing is what he needs to do.

He’s allowed the luxury of his dreams, even as a black man, while her entire life is destined to revolve around what he does or doesn’t want. What I thought about during that scene was that even if she wanted to, she literally couldn’t go in on that diner-owning dream without him. Even though they both have jobs and are making money, in the 1950s women were not allowed to open a bank account or establish a line of credit unless they had a husband to cosign.

This would be the case even if she were a white woman. Throw race into the mix, and even having a husband cosign might not help, depending on the bank (or the bank employee). Despite her life as a black woman being doubly hard than it is for Benny, none of this is mentioned. It’s all about Benny’s dream.

Again, we see a woman resigned to sexism being how it is. Nothing big enough to make a fuss over. When local sports celebrity Willie Hawkins (Michael Dorn) incessantly hits on Cassie, even though she’s with Benny, it’s played like a cute rivalry between men, rather than what it actually is. Harassment.

The script of this episode gives Benny the space to rail against injustice of racism, but it doesn’t take the same care with the equally untenable injustice of sexism. What the episode shows us is that women are “even-tempered,” and “strong” in that we can put up with a lot. Well, sure. We are strong, and we are asked to put up with a lot. I only wish that more of an effort had been made to do more than pay sexism lip service. Interesting, too, is that the only other prominent woman in the episode, Darlene, who is the alternate version of Dax, one of the most interesting female characters in Star Trek, is reduced to a walking “ditzy secretary” trope.

The episode makes mention of “the Dreamer and the Dream,” as in the fact that Sisko is both Benny, the one dreaming of a better future for black people, and the dream, meaning the fulfillment of that better future. In the case of “Far Beyond the Stars” the dreamers were all men, in that the writer/producers were all men, and the episode was directed by Avery Brooks himself, for whom I’m sure the episode was very personal and poignant.

However, it’s clear to see how the lens through which the “dreamer” sees the “dream” changes depending on who’s doing the dreaming. The autonomy of black men is made crystal clear in this episode, whereas the injustice the women face over and over is sidelined and never returned to again. There’s no outlet for them, no expression of anger. Sure, there’s sexism, but it’s used to prop up the “greater” injustice of racism. Never mind that one of the women dealing with sexism within her own community is black.

This is why we talk about needing more women telling stories, because men shouldn’t be the only ones who get to have outlets for their rage and pain. They shouldn’t be the only ones who get to have dreams. Women dream, too.

(image: Paramount)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com