Review: Gone Girl Is A Solid Noir Marred By Sloppy Storytelling and Sexism

A complicated question to ask when writing a review of the much-anticipated Gone Girl is what should be considered spoilers. The movie is heavily dependent on a twist that occurs midway through, but if you’ve read the book you’ll know that what occurs after said twist comprises the meat of the film’s narrative, not its flashbacks or slow beginning. Because of this, and because Gone Girl-the-book has been so widely read, this review will spoil the twist. Don’t read if you don’t care to know.

Gone Girl‘s book-to-film journey has been a smooth one. Novelist Gillian Flynn was brought on to adapt her own story, and she did an admirable job in not being too “precious” with her material. It is actually remarkable how much she was willing to let go of when paring down the novel. Additionally, she’s skilled at writing dialogue and utilizing voice-over. That said, the film also feels afraid to go out on a limb and be a pure cinematic experience, the sort of which can excite audiences whether or not they’ve read Gone Girl. It’s a bit too much “Based on the best-selling novel!”

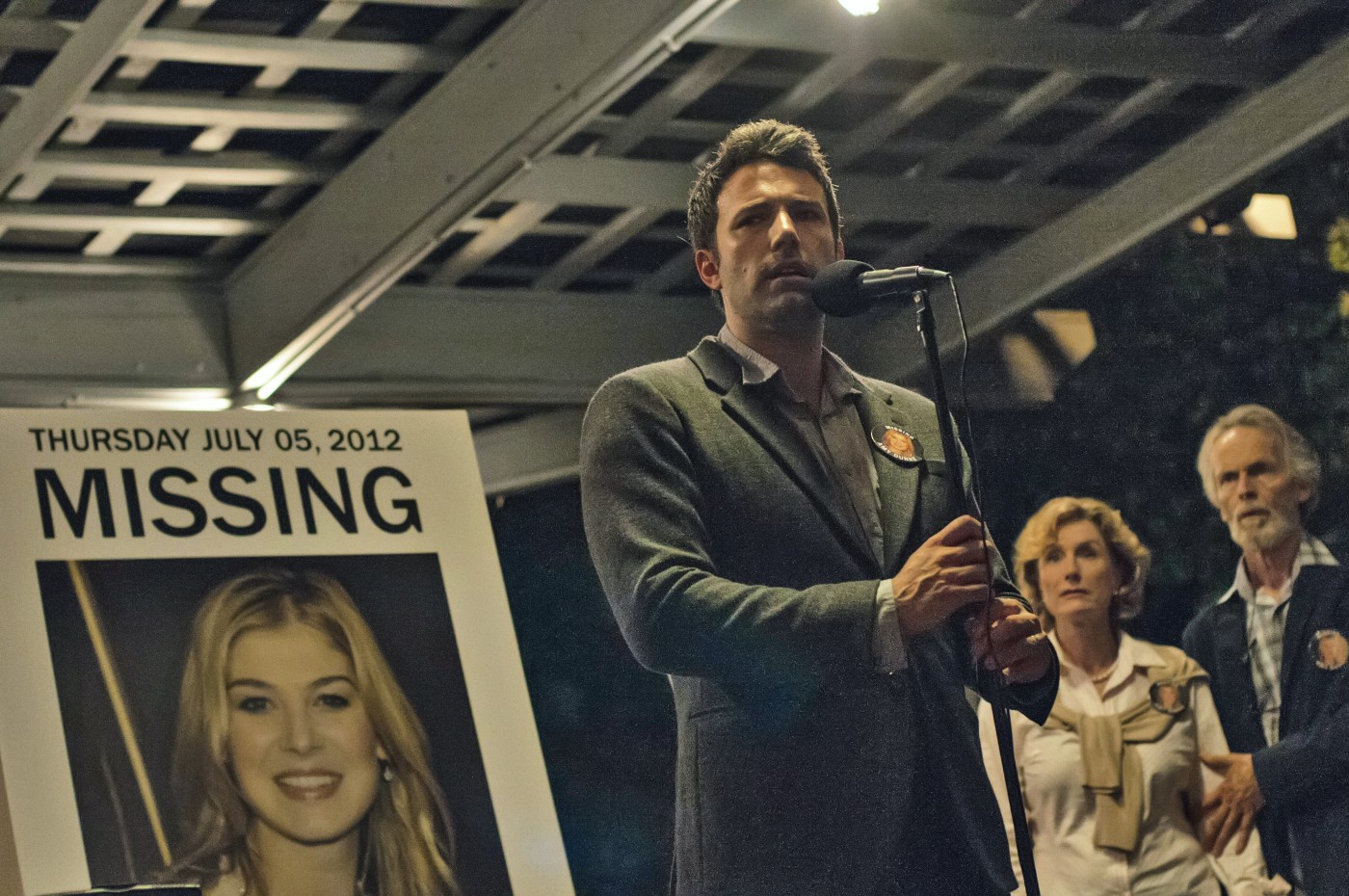

As you can gather from the trailer, the premise of Gone Girl is that Nick’s wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) goes missing, and people begin to suspect Nick (Ben Affleck) of having murdered her. The twist is that Amy faked her own abduction and framed Nick for it as a way to get back at him for having cheated on her. The surprise element works better on the page, where the audience can’t see the way Nick is behaving, because Flynn’s descriptions are similar in style to the judgmental journalism Gone Girl is critical of. But the effect is lessened in the film, because we can see Nick’s initial reaction to the home invasion. Enough shock crosses his face that any of director David Fincher’s attempts to make the audience suspect Nick as guilty of abducting and murdering Amy immediately fall flat. If you’ve read the book, you know Fincher is trying to trick us. If you haven’t, it still makes no sense that Nick would be guilty. The result is a first third that’s slow, depressing, and lacking any real intrigue. It’s obvious that Fincher’s just trying to hide things from his audience until it’s time for the wickedly comic approach that dominates the second and third acts.

Once Nick figures out what’s going on and the narrative reunites with Amy, the film picks up the pace remarkably quickly. I question the logic of even suggesting Amy could have been harmed by Nick in the first place. Why not make this a nightmarish black comedy from the beginning, where the audience, but not Nick, knows Amy’s plans… and can laugh at how quickly the cartoonish press and the police turn against him as he walks around in a fog of bewildered stupidity that reads as guilt? Had the film played to the satire from the beginning, we still would have disliked Nick for his infidelity and his apathy about the wife he believes has been kidnapped, but we’d have felt the manipulative hands of Fincher a little less. Despite the film’s sudden turn to side with Nick and attempt to make us feel empathy with him, he still has fundamental, personal flaws that make him an anti-hero. Being a murderer just isn’t one of them.

In the leading roles, Pike towers over Affleck just the way her character does in the film. Affleck’s natural tendency to play nothing on the face unless instructed otherwise works for his character, whose inability to react “normally” to his wife’s abduction quickly turns people against him. Nick has just enough apathy for the detective’s suspicion of him to seem merited, but he’s not sinister enough to suggest he’s actually guilty. It’s when he’s supposed to be the charmer, during flashbacks or in a pivotal television interview, that Affleck’s performance falls flat.

By comparison, Rosamund Pike is an absolute revelation as the sociopathic Amy, possessing the perfect blend of creepiness, weirdness, and blank-slate joy at being able to get one over on the men she perceives as having done her wrong. She falls somewhere between Hitchcock’s Marnie and a female Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, which might be part of the reason I so enjoyed her voice-over. She’s almost soulless, only showing a bit of humanity when one of her plans either hits a road bump or goes off without a hitch. Seeing her delight in framing her husband yields some of the most entertaining scenes in the film. It’s almost enough to make you want her to get away with it… almost.

The massive supporting cast is impressive, if not remarkable. Kim Dickens and Carrie Coon, as the head detective and Nick’s twin sister, are the absolute highlight of this group, with pleasant appearances from Patrick Fugit and Scoot McNairy (but isn’t it always nice to see them?) as well. Casey Wilson, Missi Pyle, and Sela Ward are funny as the media types, especially once the film becomes a dark comedy, although I was getting unbearably annoyed by Pyle’s Nancy Grace impression and Wilson’s screeching by the end. As for the stunt casting of Tyler Perry and Neil Patrick Harris, they feel out of place in the film, but neither (in fact none of the actors) bring the film down. They just aren’t an asset.

Fincher draws considerably from Hitchcock and borrows from some of the master’s best films. The mysterious ex-boyfriend Desi (Harris) is clearly influenced by Psycho’s Norman Bates (as the actor confirmed during a press conference). Nick Dunne borrows some from Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man and Jimmy Stewart in Vertigo, never coming close to either actor’s performance. And Pike’s Amy, as mentioned, draws from Marnie, along with countless other quintessential femme fatales. Cinematically, the movie’s look is wanting of the kinetic, aggressive style Fincher does so well, which could have prevented the film from feeling quite so much like merely a book-to-film adaptation. Nearly two hours of the movie were filmed with a combination of natural light and filters, which gives an impressive nightmarish look to suburbia for Affleck’s scenes but feels out of place in the flashbacks and Pike’s solo scenes. Fincher’s decision to change it up towards the climatic ending, when Pike is hiding in an estate flooded with bright light or retreats to the plastic soullessness of her home with Nick, adds energy to the final act.

Just as Gone Girl looks better in the second half, the movie’s snails pace at the beginning picks up to a nice trot towards the end. Almost in every way–narrative, character development, cinematography, editing—the second half is so much better. Even if I wish Fincher had sliced and diced the first part, the movie is still certainly worth watching. The production design is so clean and sterile that it adds to the overwhelming creepiness, and the score is the best one Trent Reznor has ever produced. And Amy’s brilliant manipulation is fascinating to observe as a third party. It’s similar to the sick fascination I had watching Scarlett Johansson in Under the Skin. Still, the movie is never more than a a solid and entertaining, if overly long, mystery noir. It feels like something we would have seen in the late ’80s or ’90s, as has been the case with so many films from this year. It’s not the masterpiece I’m hearing it be hailed as.

And it is hard to dismiss the overwhelming feeling that, while the film might not be misogynistic, it certainly supports a disturbing depiction of women as a threat to the male domain. It is a given in Gone Girl not only that Amy is “the bitch” (a fact established even before she goes missing), but that the same is true of most of the other female characters in the film. Only the sister and the detective, both of them presented as more traditionally “boyish,” are treated with sympathy. And being the second film this year (unless I’m missing some) to have a woman falsifying claims of rape and domestic abuse to “get” the stupid guys so willing to believe them (Amy is shockingly similar to Eva Green’s character in a Sin City: A Dame to Kill For), along with the continuing trend of using rape as little more than a quick plot device, is a problematic trend. Is Fincher himself sexist? No. I don’t think so. Could Gone Girl appeal to and feed a growing tendency in society to justify the idea of women as threat? Absolutely.

Lesley Coffin is a New York transplant from the midwest. She is the New York-based writer/podcast editor for Filmoria and contributor at The Interrobang. When not doing that, she’s writing books on classic Hollywood, including Lew Ayres: Hollywood’s Conscientious Objector and her new book Hitchcock’s Stars: Alfred Hitchcock and the Hollywood Studio System.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com