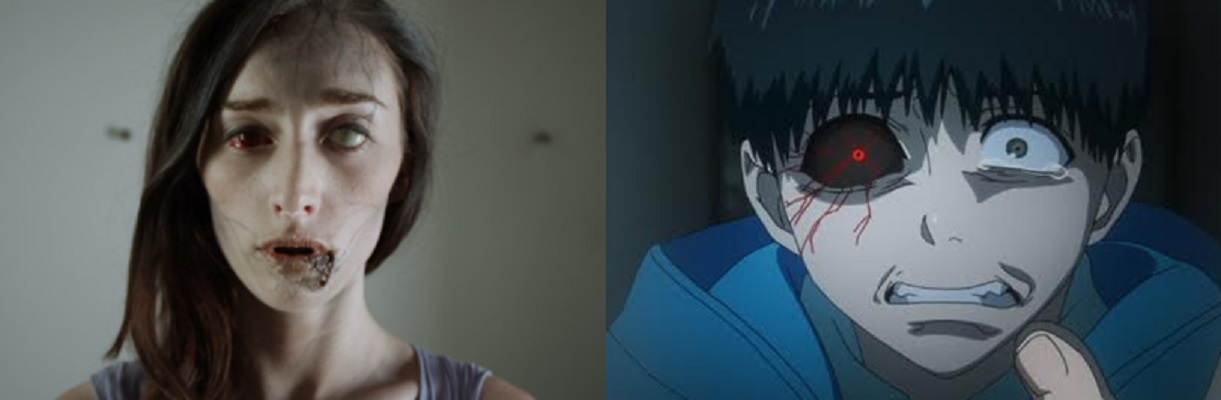

Am I Becoming a Monster? How Tokyo Ghoul & Contracted Demonstrate the Horror of Healing From Trauma

Content warning for discussion of sexual assault and eating disorders.

I love horror. More to the point, I love bad horror. My Netflix ratings and suggestions are a mess of horror movies with terrible acting, sloppy ideas, and even worse execution. It was this unconditional love for the genre that led me to watch Contracted (2013), a flick about a queer gal, Samantha, who ends up being sexually assaulted at a party by a dude, which leaves her infected with a zombie virus (that apparently operates like an STI).

To be honest, there is little that is super great about this movie, but I still kind of love it. Theoretically. And that’s because it deals with a really interesting core premise. No, not “what if the zombie virus was an STI”—It Follows handles that metaphor way better; rather, Contracted tries to show the mental and emotional turmoil that Samantha undergoes as her body decomposes, turning her into a zombie. Samantha suffers from total biological degradation: her teeth and nails fall out, she bleeds everywhere, and there are unfortunate incidents with maggots coming out of sensitive orifices—all compounded by Samantha’s inability to understand what is happening to her. The crux of the movie is Samantha’s grief and trying to fight against her inevitable monstrosity.

Sure, she becomes a flesh-eating zombie. But her process of getting there is what makes Contracted stand out for me.

And then there’s the anime Tokyo Ghoul (2015), the first episode of which gives me shivers every time I watch it for a lot of reasons; for one, it’s a beautiful pilot (with exceptional sound design) that sets up a world cohabited by humans and ghouls, monsters who appear human but actually eat humans. But most importantly for me, it operates as a near-perfect allegory for disordered eating—whether it means to or not.

Tokyo Ghoul introduces us to Kaneki, a young man who is really into books, as he attempts to navigate dating. But due to an accident, Kaneki becomes a ghoul-human hybrid. (Ghouls have to be born ghouls, I think, but Kaneki receives an organ transplant from a ghoul. I’m sure there’s ghoul science in there somewhere.) So instead of being a series about a shy boy trying to get a girl to see and love the real him, Tokyo Ghoul—its first episode at least—becomes about Kaneki’s denial of his new self and the emotional and physical ways he rages against what he won’t admit: he is now a ghoul and will only survive by eating humans.

Though most people would tell you Tokyo Ghoul should never be compared to Contracted, both stories look at how we view grief, acceptance, loss, fear, anger and moving on in eerily similar ways. Each show us how using monsters can function as brutally honest vehicles for this conversation. Having to accept themselves now as “monsters” causes Kaneki and Samantha to shift their self-perceptions, forcing both to accept their pain and trauma in an attempt to save themselves.

Kaneki’s process of acceptance veers through the typical stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and then acceptance. He’s grieving the loss of what he considers to be his humanity. Yet, as the first season progresses, we see Kaneki struggle to remain both human and a ghoul. He only eats sugar cubes that are made from humans that have died from suicide, and he aligns himself with others who refuse to kill humans for food. Yet the show reveals that his refusal to give up his humanity prevents him from accepting himself, and ultimately saving himself and his friends—both human and ghoul—from death.

It’s not until Kaneki accepts and embraces his new self that he is able to survive. Torn between ghoul and human, Kaneki is doomed to die. But accepting himself as a ghoul gives Kaneki the strength and confidence he needs to not only survive, but to thrive. Kaneki becomes stronger when he accepts the sides of himself that are at odds; rather than suppress his monstrous side in an attempt to restore his humanity to dominance, he accepts his ghoulish nature, incorporates it into his sense of self, and becomes better for it. (Much better.)

Samantha’s process of acceptance doesn’t reach the same place as Kaneki’s, but her struggle to deny and change her circumstance follows the same basic patterns: denial, anger, bargaining, depression. She never makes it to complete acceptance (at least not in the same way as Kaneki), and in contrast to Kaneki’s process of acceptance, Samantha shows how emotionally difficult surviving trauma can be. As her body degrades, Samantha’s mental stability also slips; unable to identify what is wrong with her, Samantha can’t understand what is happening to her body. She can’t fight it because she doesn’t know what it is—and she doesn’t have any help along the way. Kaneki is the opposite; his acceptance comes from understanding his change and seeing ways to still be good despite being a ghoul. Kaneki is guided, helped through this change by the spirt of Rize, the ghoul whose organs are now in his body. Reaching self-acceptance requires understanding, work, and support—Kaneki is given space for all three, while Samantha is not.

While looking at the emotional process behind acceptance, Tokyo Ghoul and Contracted both also look at how trauma and hurt factor into changes in identity and how painful the process of healing (as with Kaneki) or failure to heal (Samantha) can be. It’s no surprise that both Tokyo Ghoul and Contracted resonated with me as I move through my own process of acceptance and healing. While I’m obviously not becoming a literal zombie or a ghoul, the process of recovery from an eating disorder and from abuse trauma is a painful process. It doesn’t feel good—not at first, anyway.

Watching Kaneki cry as he tries to eat his favorite food, aware that he can’t because his body will no longer allow him to do so, hit me harder than most other media that try to talk about eating disorders. Kaneki’s struggle as he binges—hurting himself in a process to be okay and to be normal, ultimately forced to eat despite every molecule of his mental and emotional self protesting—is an excruciatingly honest portrayal of how difficult recovery is.

Of course we’re not monsters, but healing hurts, and the self you’re learning to accept is a different self from the wounded and angry one you’ve known for so long. The first episode of Tokyo Ghoul ends with a black screen and the sound of Kaneki swallowing, and the gravity of that moment of acceptance is one I know well: fear—but also the strength that comes from it.

(Tokyo Ghoul images via Funimation; Contracted image via IFC Films)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

Kaitlin Tremblay is a writer, editor, and game maker living in Toronto, ON. Kaitlin’s games have focused on using horror to talk about feminism and mental illness, and have been featured at Indiecade, Different Games, and in other art exhibitions. She is the author of the upcoming book Ain’t No Place for a Hero: Borderlands (ECW Press, 2017), which critically examines the role of subversive storytelling in the Borderlands franchise. Her writing and games can be found on her website thatmonstergames.com and you can follow her on Twitter at @kait_zilla.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com