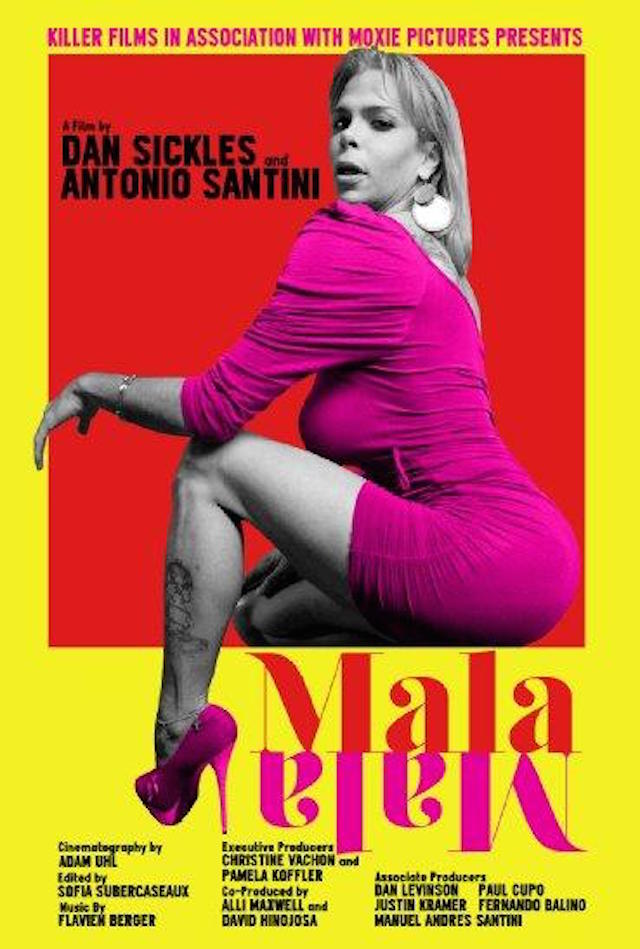

Interview: Directors of Transgender Community Documentary Mala Mala

In 2014, co-directors Dan Sickles and Antonio Santini premiered their documentary Mala Mala, a look at the lives of 9 members of the trans-identifying community in Puerto Rico. Filming turned out to coincide with a landmark bill being passed which gave rights to Puerto Rico’s LGBT community. I spoke with the directors about their fascinating film that celebrates the strength and bravery of their subjects, without sugarcoating the hardships of their lives. The film began its limited theatrical run this week, with gradual rollouts to follow.

TMS: What made you want to document this specific time in Puerto Rico?

Dan Sickles: About 4 years ago, we were in Austin and had our first intimate encounter with someone who was just beginning their transition. We ran into her at a bar and ended up hanging out with her for something like a day and a half. We had our camera crew with us and made a short, looking at what it meant to be transgender and what it meant to transition. And after that experience hanging out with her, we were just so curious and wanted to find ways to unpack our thoughts. So we started to try to figure out ways that we could develop a feature and wrote down a list of locations. And Antonio was born in San Juan Puerto Rico, so that was obviously one of the places we included, and it turned out to be one of the most interesting places.

TMS: Was there a time that you considered making a film about the trans-community which didn’t focus on a single area?

Sickles: Absolutely.

Antonio Santini: But then we got to Puerto Rico, and we were there for about 2 weeks, we assumed we would leave with some sort of movie.

Sickles: My mom was like, so are you guys done?

Santini: We hung out with April the first night we were there, and it was one of the craziest nights I’ve ever had. It ended with us in a parking lot at 7 in the morning, with April running around in nothing but her tuck and her wig. It was just such an adventure.

Sickles: We went to a drag house, with a drag family. Mother, grandmother, sisters. They were all there. It’s called The Doll House, and that’s were April lives. So that’s where we started. And then something like 3 months later, we met Sophia at her club. She’s the New Yorker who immigrated to Puerta Rico. And around that time, we realized that we had found ourselves knee deep in this, and it was going to take much longer to make a film—much longer than 2 and half weeks. So we just kept coming back and finding more and more. It was like we were mining and turning up gold, so we couldn’t just walk away.

TMS: How did you meet April?

Santini: I went to school with April as Jason, and she was the only outwardly male person who would perform his femininity. He hadn’t even come out as gay. But because he was a feminine male, and would dance, people would constantly talk about him. Then suddenly, we looked online and realized that April was becoming this famous drag queen. We couldn’t believe that he had made the jump from being in that very difficult masculine space of high school to decide he wanted to be the best drag queen in Puerta Rico. And that’s why we wanted to go there. Because having had to deal with that very intense environment, and being brave enough to be herself, was maybe more interesting than being a drag queen in LA. We felt like she was coming up against more obstacles in Puerto Rico.

TMS: Having known her as Jason, did you sense any apprehension from her about reconnecting with someone from her past?

Santini: Not really. It was great for us, because she was one of the first people to say yes in the beginning, when people thought we were making some kind of weird YouTube video. But during the first interview, she did ask me “hey in high school, why did you call me f****t.” And I was like “did I?” And she said “yeah, you did.” And I just had to say, “it was the culture I was born into.” And we realize that is what the film is going to have to be about, talking about things which challenge us, too. Because we weren’t just going back to find new subjects every time, it was a personal journey of exploration for us as well. It wasn’t our fascination with them, but learning something about ourselves.

TMS: Was there are point when you considered putting yourself into the narrative, or were you concerned about taking away from their story?

Sickles: We played with the idea of including ourselves more. Because the experience of making the movie could almost be chalked up to this weird road trip kind of adventure that just went on for years. So we talked about that at one point. Early on, we were in a horrible car accident while filming, so we have all that footage. April was with us, dressed as Marilyn Monroe, our car on fire, and April ran away because she didn’t want to be there when the cops arrived.

Santini: She had to leave because with her in the car, in a dress with cameraman, the cops would have assumed we were doing drugs or something. That is the culture in Puerto Rico. So after we dealt with our own PTSD from the car accident, we thought, “Why did April literally have to flee the scene of an accident?”

Sickles: And we have that on film. But in the evolution of the film, particularly when we started editing, what remains of the 89-minute film is the most interesting material. And that didn’t include us, because this world exists every day without us, too.

TMS: How did you select people for the documentary?

Sickles: Before we started filming anything, we set up a number of rules as to how we would approach people and tell their stories. And one of those rules was to keep the umbrella term of transgender as wide as possible. We didn’t want to create anything essentialist or make some kind of Trans 101 film. Because it was so obvious that within the community, there were so many different people and meanings. One of the people who really tested those boundaries was Paxx. He enters the film and doesn’t really identify as a transgender man, as much as a trans masculine who is gender queer. People watch the film and sometimes say “so there is a transgender camp and drag camp.” Because we tend to cling to this idea of binaries. But really, there aren’t just two groups. The transgender experience is just so multi-dimensional, both in terms of gender and identity.

TMS: Were you aware of the political movement happening in Porto Rico when you first began this project?

Santini: No, because the news wasn’t covering it.

Sickles: We were the only cameras there when the bill actually passed. We saw one person with a camera, but I think they were a friend of someone, not someone from the news.

Santini: Yeah, it wasn’t a front page news story or anything like that.

Sickles: In the film, when they are holding up the Pride flag in front of the capital, they were posing for us and one other camera. The bill literally passed, they walked out onto the steps, and we were the only people with a camera there.

Santini: That day, no one was there. Later on, they had the march, and that got a little bit more coverage. And then they were treated like this group we only see in the shadows finally coming out in the day light.

Sickles: It was actually before the bill passed, and it was interesting because all these people showed up for the march, but no one showed up when the bill got passed. And yet, that legislation only exists in 19 states in America. So when you think of Puerto Rico as some place which is a little behind, and yet they passed the law. So considering how poor and relatively un-educated it is, this was an anomaly. We don’t normally see places like that passing those types of laws. They are literally twice as poor as the poorest state in America, and their unemployment is much worse, and yet, they are still trying to be inclusive.

TMS: But while they’re more progressive legally than a lot of the states in the US, considering what you said about how the police would have respond to April or how the news covered the march and bill passing, it sounds like culturally, they haven’t caught up.

Santini: There was an anti-gay, so-called pro-family march, which was going on behind the capital. And it felt pretty violent. Not physically, but definitely verbally. We heard lots of threats of murder said there. Things like “these people should be killed” or “God should smite them.” We filmed it, but we couldn’t include it, because it was just too jarring for the tone of the movie. You’re falling in love with the subjects, and then you hear people threatening them with death and hell. But that day, there were 2 marches, and this pro-family march had something like 200,000 people, and on the other side there were 50 to 100 members from the LGBT community protesting it.

TMS: Did you show any of that footage to the subjects of the film?

Sickles: We didn’t, because they were there and knew what was going on, even if they didn’t hear it. But that footage was in the film for a very, very long time, and there were lots of discussions about including it. I felt obligated that everyone knew where we stood on the subject. But we ultimately took it out of the cut because we didn’t want to give those protesters the same space we were giving our subjects. And this film is about them and their strengths and the film should be something forward-looking.

TMS: One of the issues you have to deal in the film is how prevalent the sex industry is and issues members of the trans community face, such as condoms and safety.

Santini: In the movie, one of the people who shows up to speak was a trans woman who was also a sex worker. Even when you see the bus going to the march for a public demonstration, the people from the trans community that came were the women who we saw working on the streets. So there was no question about including sex workers, because they really are the movement.

Sickles: And a lot of the women we met who were sex workers, make it clear that this is a means to an end, not a career choice. There are some who do see it as a career choice and want to be a part of a union, and that is cool to see as well. But someone like Sandy says this is how I eat, this how I pay my rent. And she’s good at it.

Santini: Sandy even says, yes this is how I eat and live, but this is also how I can afford to even be a woman. Because they have to save up to get the operation in another country where it is legal and then buy their hormones illegally. So the government is lacking in all these areas. Health care, sex education, jobs. All of which causes the sex industry to rise in this kind of vacuum. A lot of them go into sex working as boys, saying they’ll do it to save to have the operation and then be done. But when they come back, they can’t find other jobs because they’re trans, and can’t afford their hormones unless they become sex workers again.

TMS: Since the law was passed, have you seen changes regarding employment or health in Puerto Rico?

Sickles: Slowly. Sandy was able to get a job for a time because of these changes under the new law. But the government is still just trying to collect data, because there are no statistics regarding how many people are part of the trans community. It’s hard to serve a community when you don’t know how many people you’re talking about. So it’s just starting. Which is so interesting. In terms of legislation, they are so much further ahead, but there are still these deep, deep holes they have to fill in.

Lesley Coffin is a New York transplant from the Midwest. She is the New York-based writer/podcast editor for Filmoria and film contributor at The Interrobang. When not doing that, she’s writing books on classic Hollywood, including Lew Ayres: Hollywood’s Conscientious Objector and her new book Hitchcock’s Stars: Alfred Hitchcock and the Hollywood Studio System.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com