Iranian-Americans Have Been Through a Lot. Why Don’t We Talk About It?

My five-year-old son and I have a bedtime routine—designed by him—that we follow every night without fail. First, we snuggle, and then once he can barely keep his eyes open, I give him a sip of water and tuck him in. As I walk out the door, he always calls after me: “Don’t close the door all the way! I’ll get you if I need you!” Sometimes, he repeats the mantra, “I will not have a nightmare tonight, I will not have a nightmare tonight, I will not have a nightmare tonight.”

The logical side of my brain tells me that kids hate bedtime and the dark, and being alone. They need a routine to make them feel safe. The other, more catastrophic side of my brain worries that this is a sure sign I’m passing down my anxiety disorder to my child. True to form, even my anxiety gives me anxiety.

I can trace my first memory of experiencing panic back to when I was five years old. I woke up in tears from a nightmare that my dad had died. As my mom consoled me and tried to calm me down, I remember being afraid that if I revealed the details of the dream, I would tempt fate, and it would come true. As a child, I often experienced feelings of dread. I was certain that something terrible was just around the corner. This may have been a result of inherited trauma and the byproduct of our family escaping Iran after the revolution. My parents didn’t talk much about that time in our life, and I didn’t divulge the “worst-case scenario” thoughts that kept me up at night. I was worried that if I did, it would confirm there was something really wrong with me.

Mental health, or lack thereof, remains a taboo topic among the Iranian diaspora. As immigrants who left their country under duress, my parents experienced so much loss and tragedy in their own lives, it’s possible they thought it was normal to be in a constant state of angst. We also come from a country that’s historically been preoccupied with keeping up appearances, even while its citizens are encumbered by economic anxiety, “morality” laws, and gender segregation. It’s no coincidence the current regime shut down the internet as protests raged following the death of Mahsa Amini—in part, because they were desperate to hide the upheaval from the rest of the world.

This pattern of projecting a shiny exterior has long been absorbed in the culture. Regardless of what’s going on behind closed doors, many Iranians believe they should present as a happy (financially stable) family, with kids who are thriving. To talk about your problems to anyone outside of your household would be considered a betrayal. As a society, we prioritize privacy more than most celebrities do.

Perhaps that’s why it wasn’t until I was eighteen years old and sitting in a college psychology lecture, that I discovered there was actually a name for that nervous feeling in the pit of my stomach. I suffered from anxiety disorder. Finally, I could name it, but it would still take me a decade to seek professional help to tame it. My parents were supportive when I told them I’d started seeing a therapist, but I knew they weren’t exactly comfortable that I was spilling my guts to a stranger. Any meaningful shift on mental illness would not only have to come from inside our community, but also from someone of their generation.

And eventually, it would, in the form of an Iranian psychologist with a popular radio show. Strike up a conversation with any Iranian and chances are they’ve listened to Dr. Holakouee (Also known as Dr. H. He’s kind of our Dr. Phil). Known for his no-nonsense and blunt advice, my parents frequently reference his philosophies. Years ago, my mom attended one of his conferences and asked him about the cause of my anxiety disorder. He told her it was a common trait among kids who wished their parents were dead. Needless to say, I don’t always agree with his advice, but I’m glad he’s helped destigmatize mental health struggles within the Iranian community.

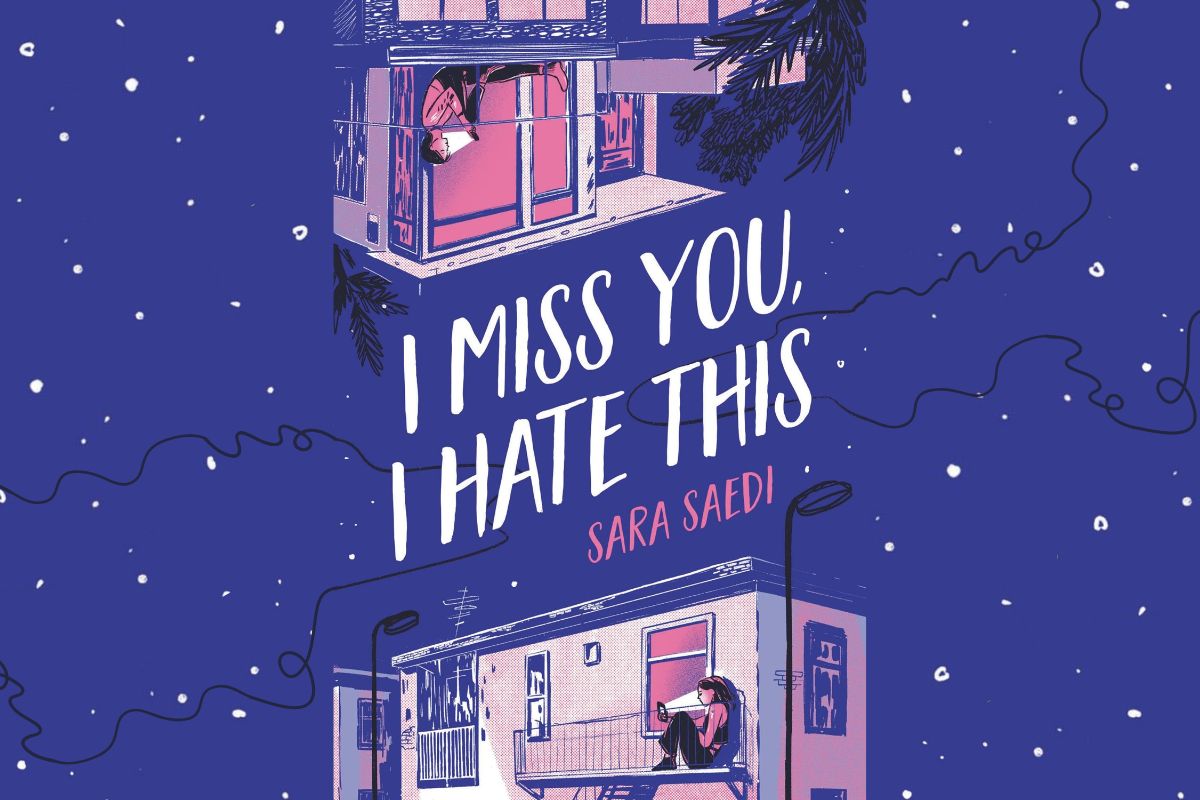

I don’t know the exact cause of my anxiety, but recently, I tried to grapple with it in my work. My latest novel, I Miss You, I Hate This tells the story of two teenage best friends living through a pandemic. One of them is Iranian-American and suffers from an anxiety disorder. It’s the most I’ve ever disclosed about my own struggles, and writing Parisa’s journey was incredibly cathartic. Hopefully, as many of us start to speak openly about our internal battles, today’s generation of young people won’t be thwarted by mental health stigmas. I know my younger self would have benefited greatly from reading a book about a girl wading through a sea of irrational fears.

As a writer, I’ve always said my overactive imagination was a blessing professionally, but terrible for me personally. But as a mom, I’m no longer sure that’s the case. If my son’s imagination does end up taking him to some of the same dark places, I know I can help guide him through it. I just hope he’ll stay true to his word and get me if he needs me.

—

I Miss You, I Hate This

Five Feet Apart meets Kate in Waiting in this timely story of two best friends navigating the complexities of friendship while their world is turned upside down by a global pandemic.

The lives of high school seniors Parisa Naficy and Gabriela Gonzales couldn’t be more different. Parisa, an earnest and privileged Iranian American, struggles to live up to her own impossible standards. Gabriela, a cynical Mexican American, has all the confidence Parisa lacks but none of the financial stability. She can’t help but envy Parisa’s posh lifestyle whenever she hears her two moms argue about money. Despite their differences, as soon as they met on the first day of freshman year, they had an “us versus the world” mentality.

Whatever the future had in store for them–the pressure to get good grades, the litany of family dramas, and the heartbreak of unrequited love–they faced it together. Until a global pandemic forces everyone into lockdown. Suddenly senior year doesn’t look anything like they hoped it would. And as the whole world is tested during this time of crisis, their friendship will be, too.

With equal parts humor and heart, Parisa’s and Gabriela’s stories unfold in a mix of prose, text messages, and emails as they discover new dreams, face insecurities, and confront their greatest fears.

I Miss You, I Hate This releases October 11 and is available at for pre-orders now.

The Mary Sue may earn an affiliate commission on products and services purchased through links.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com