Jen Petro-Roy Addresses Body Image and Eating Disorders in a Powerful Pair of Middle-Grade Reads

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, at least 30 million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the U.S. It affects all races and ethnic groups, genders and sexualities, and has no age limit with a reported 13% of women over 50 engaging in an eating disorder behavior.

Despite the fact that it’s so prevalent, media that handles eating disorders loves to have the emotional angst of one, but rarely deal with the healing process. One of the things I realized, in researching for The Mary Sue’s Teen Drama event that took place earlier this month, was that a lot of shows and films will have “48-hour anorexia.”

A character will have an eating disorder for an episode, and within that episode it starts, they are “exposed” dramatically, and it ends with them being told they are perfect, and recovery is never highlighted. It uses the emotional weight of the topic without fully exploring what it really means, not to mention these shows rarely ever deal with fatphobia, stigma, and the long road to recovery these mental illnesses can have.

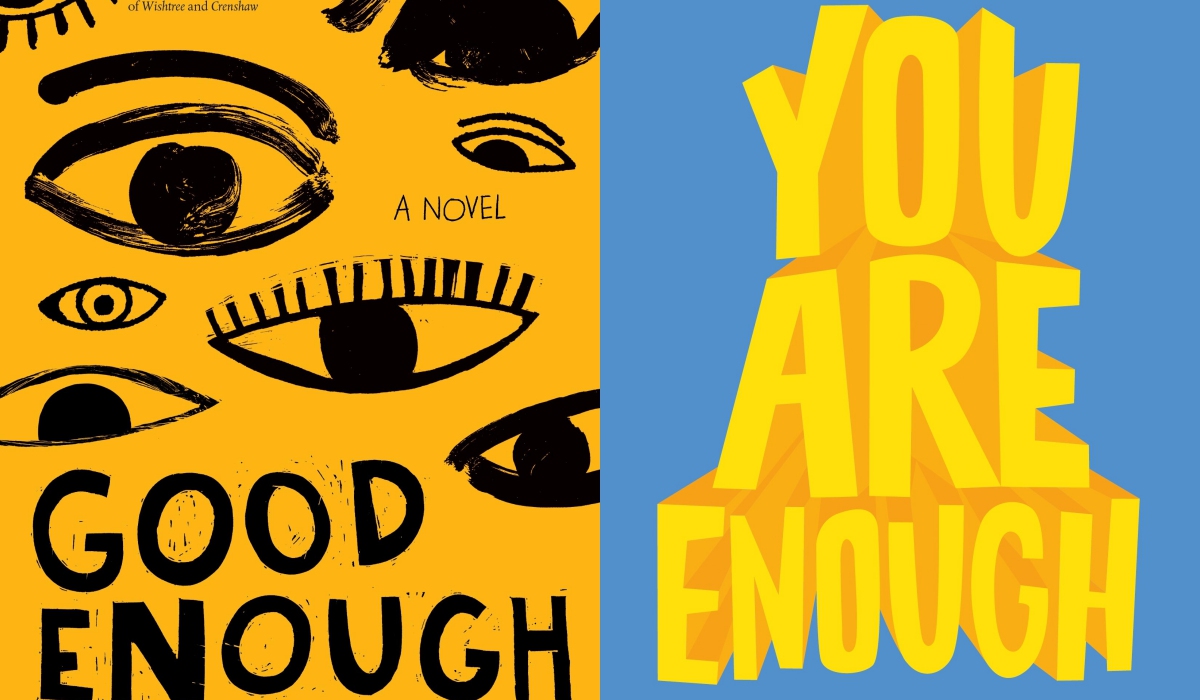

That’s why Jen Petro-Roy’s dual books, the non-fiction You Are Enough and fiction Good Enough, are such refreshing and necessary reads right now for middle-graders.

Good Enough deals with a twelve-year-old girl named Riley who is currently at an inpatient treatment center where she’s receiving treatment for anorexia, which deals with her process towards recovery. You Are Enough is a self-help book that attempts to give guidance and references to young people (including lower income and LGBTQ+ kids) on how they can get help on their process to recovery.

We got the opportunity to speak to Jen Petro-Roy, over email, about the two books and using her own personal experiences to help others.

Both titles will be released February 19th 2019 from Feiwel & Friends.

(image: Feiwel & Friends)

TMS: Writing one book is hard enough, but writing two and having it be something so personal to your own experience sounds so intense. How did you make sure to self-care during the experience? What helped you stay grounded in the work?

Petro-Roy: Writing these two books was definitely one of the most intense writing experiences I’ve had, exactly because I had such a personal connection to them. Riley’s experience as she progresses through treatment and recovery is very similar to the journey I myself took, and many of her feelings were ones I remember having myself.

Something I didn’t quite expect was how vividly I would remember these emotions. Even though I have been recovered for a while now, it was striking to put myself back in the mindset of someone actively engaging in her eating disorder. It was both heart-wrenching and healing to remember where I once was. It made me realize how far I’ve come in my life and how much work I put in to get here.

Writing these books was wonderful in that way, since I got to go through a sort of catharsis and a self-affirmation at the same time. That balance, along with reminding myself how much these narratives were going to help others and balancing the writing process with distracting forms of media (Funny books! Romance books! Comedies on Netflix!) gave me my equilibrium back.

TMS: One of the things that really got me interested in this dual book release was that often teen or adolescent media will address eating disorders, show the severity of it, but then within 48 hours, it’s over. There is a lot of trauma and not a lot of focus on recovery. As you were writing these books what were some of the myths you wanted to dispel about eating disorders? Especially things the media get wrong?

Petro-Roy: I am so glad that you picked up on that! One of my goals in writing Good Enough was to focus more on the “recovery journey” than the sickness itself. In many of the books I’ve read in the past, the narrative often focuses on the gritty details of someone descending into sickness, along with the behaviors that accompany that decline. In fact, watching “tv specials” and reading books like this has been demonstrated to increase behaviors in many sufferers, simply because they can get ideas of other behaviors to adopt in their quest for thinness.

Besides avoiding triggers like this, though, I also wanted to portray hope in my books. We all know that eating disorders are harmful. But I also aimed to depict the hope amidst the struggle. In Good Enough, Riley wavers in her desire to recover throughout the early part of the book. But the entire time, she does have a healthy voice in her brain that urges her on. She has counselors, therapists, and friends around her who provide her with affirmation, advice, and love.

She works hard, too, and there are moments of brightness along her dark journey. In the end, I wanted to show even though recovery is a struggle, that it’s worth it; that the moments of triumph and lessons learned along the way contribute to strengthening one’s character.

One final thing I wanted to portray is that not everyone who gets sick fits into a single mold. People who identify as male and nonbinary get eating disorders People who are LGBTQ do, too. Eating disorders encompass more than just anorexia and bulimia, too—there’s binge eating disorder, ARFID, and EDNOS (Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.)

So many people suffer, and each one of them matters. You don’t have to be super skinny to have an eating disorder—in fact, people in larger bodies often struggle more because society is systemically constructed in a way that discriminates against them. Thus, when they get caught in a disordered eating cycle, they are often praised for their weight loss. Even by doctors! And even when that weight loss and its accompanying behaviors are harming them.

(image: Feiwel & Friends)

TMS: In Good Enough, one of the things Riley says in the book that really stuck out to me was, “I know there’s nothing wrong with eating a lot. Or being fat. I just don’t want to be fat.” I feel like a lot of people who struggle with their weight are also struggling with this internalized fatphobia where they don’t “hate” fat people, but see fat on their body as ugly. How did you strike the balance of addressing both the mental issues surrounding eating disorders, but also the social stigma of weight?

Petro-Roy: Being aware of this stigma and not adding to it was one of my chief concerns for this book. For those suffering from eating disorders, as Riley is from anorexia nervosa, one of the chief symptoms is an irrational fear of weight gain.

That’s the key word here: irrational. When I described Riley’s thoughts and fears, I wanted to make sure that even when she wrote about how she was afraid of becoming fat, that it didn’t come across as judgmental towards those who do live in larger bodies.

(Full disclosure: I still live in a thin body, which means that I have thin privilege. I don’t have to exists in a society that actively discriminates against me on a daily basis and I don’t have to steel myself for comments from strangers in public. That privilege is absolutely real, and that bias exists, even for those who claim that they don’t stigmatize against fat people.)

There is nothing wrong with being fat. Those in the fat acceptance movement (which is quite different than the current Instagram-trendy “body positivity” movement and originated as a movement fighting back against the oppression of fat people) have embraced the word “fat.” The word “fat” is a descriptor, the same as blue-eyed and freckled are. There should be no judgment involved in body size.

But, as we know all too well, there is. Even subconsciously, there is judgment. But there also can—and should be—an awareness of that judgment. And as Riley grows and learns throughout the book, I wanted her to become aware of both her conscious bias and her unconscious ones, and to ultimately realize that the negative voice in her head wasn’t based in reality.

TMS: As I was reading the books, I kept thinking about myself at twelve and how that is when my anxiety really started to manifest itself and thinking it was “weirdness.” At the time I remember thinking that my new normal was going to “fix myself” to be perfect. As an adult looking back, what are some of the revelations you’ve realized about how your younger self dealt with stress?

Petro-Roy: Oh, I’ve had so many revelations in my life that I could write a book about them. (Wait…) All kidding aside, writing these books really did make me look back on the adolescent I used to be. In middle school, I had a similar experience where I made a vow to be a “model student.” I wanted to get good grades and act “perfectly,” whatever that meant. I also struggled with OCD in seventh and eighth grades, but once I started to get that (fairly) under control, I never really acknowledged my struggles to anyone else.

As both a kid and even still to some degree as an adult, I am someone who has a hard time admitting that I’m struggling and subsequently asking for help. This resistance to asking for help, along with my perfectionism, was one of the things that led to me developing an eating disorder, and my failure to admit how hard recovery is was what led me to stay sick for so long.

One of the things that I stress in You Are Enough and depict Riley realizing in Good Enough is how important than vulnerability is. Ultimately, none of us are perfect, even though it sometimes seems like so many media figures are. We are all wonderfully flawed. And it’s by embracing and talking about those “flaws” that we can connect and realize that perfection is way overrated. This opening up is so much healthier than harming yourself in whatever way.

TMS: Despite being for middle-grade readers, I found myself getting emotionally drawn into both works because body image issues don’t go away when you are older. Especially in the era, we live in today where so many images are tuned/changed. One of the biggest things is that we may hear from our families that we are enough, but the media can tell us something else. How do you, as a mom, as a woman, as a human being, attempt to navigate those waters?

Petro-Roy: It’s definitely a hard journey. I know that even in my social media feeds, I encounter numerous messages daily that tell me to look a certain way, act a certain way, or interact with my children in a certain way. There’s always so much pressure to present an image, which is why I make a conscious effort to streamline my life so that only the positive, affirming messages get in.

That’s not to say that I live in a bubble, but I don’t follow accounts that focus on weight-loss or present a “perfect life.” I don’t weigh myself, either, so that my kids won’t learn that a number is something to obsess over. And when I exercise, I focus on how it makes me strong and capable, instead of the way I used to view it, as a calorie-burning chore.

Above all, I try to choose my words carefully. I talk to my kids about health and food in a way that stresses nourishment and balance. Desserts are okay! Food is yummy and gives us energy! And I make an effort to build myself up and do the same to those around me. That’s not to say that I don’t have my days of struggle and anxiety (because boy, do I), but I try to remember that there is only one “me” out there, and that when I’m obsessed with my image and my appearance and how “lacking” I am, then the good parts of me fade away. I want them to shine instead.

TMS: Finally, I love that you provided resources for people to find what they need. It’s so important that people know recovery isn’t a one size fits all. In your research whom did you find was being the most ignored in terms of getting this kind of help?

Petro-Roy: Luckily, the medical and eating disorder communities are growing more and more aware that eating disorders can affect anyone, regardless of size, gender, socioeconomic background, or race. I was lucky enough to interview a variety of people, from nutritionists to medical professionals to those who from various backgrounds who have recovered themselves.

Overall, though, I struggled the most with finding resources for those who identify as LGBTQIA+, especially those in the trans community. The intersection of body image and identity is so intertwined, and it’s so important that we strengthen our collection of these resources, both in print, online, and especially in treatment centers, with specially trained professionals.

(image: Feiwel & Friends)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com