Underground Caves, Deep-Sea Labs, and Learning Not to Be a Jerk: Training as an Astronaut

In advance of the PBS special, Beyond a Year in Space, which premieres on Wednesday, November 15, at 9PM EST, I was able to speak with Jessica U. Meir, a member of NASA Astronaut Group 21, about her experiences as an astronaut. Meir and her Group 21 teammate, former Navy pilot Victor Glover, both appear in Beyond A Year in Space to discuss how NASA is preparing for the next generation of deep space travel. The documentary (which I highly recommend!) looks at how Scott and Mark Kelly’s twin experiment, and other NASA studies and advances, will make it possible for us to reach Mars and beyond.

Before becoming an astronaut, Meir worked as a biologist studying the physiology of animals in extreme environments. However, now that she’s at NASA, she’s learning all the same skills as the rest of her astronaut class.

“Even though I’m a scientist, I get the same training as the military pilot does,” Meir explained. “Everybody in my class got the same training, despite our background. Because when you’re on the space station, you are a generalist. There are only six people up there, so everybody has to be able to do everything. You know, I’ll be doing science, but I’ll also be fixing the toilet when it breaks, I’ll be going for a space walk … We’ll all be sharing the load to do everything.”

Astronaut Candidate Training

“The first two years that you’re here, you’re in what’s called the astronaut candidate training,” Meir said. “You have to demonstrate proficiency in five main areas. The first is flight training. I’d always wanted to fly, so I have actually had my private pilot’s license before this job. But if you didn’t have prior military aviation experience, which I didn’t of course, we went to the navy base in Pensacola to learn how to fly there. That, for me, was almost like a dream within a dream, because I had always wanted to fly a jet – but because I didn’t join the military, I didn’t think that I would ever be able to do that.”

NASA trainees fly the T-38 jet in pairs of two, and they each have a required number of hours. While the flight experience is valuable from a practical perspective, it’s also important psychologically. “You have to work together as a team,” said Meir. “You’re making quick decisions that do have real consequences and real risks. That’s really unique for what we do, because a lot of times when we’re doing other types of training, it’s always a simulation. So no matter how hard you psychologically try to prepare for a simulation, it’s still a simulation. So it’s really valuable that this training has real consequences.”

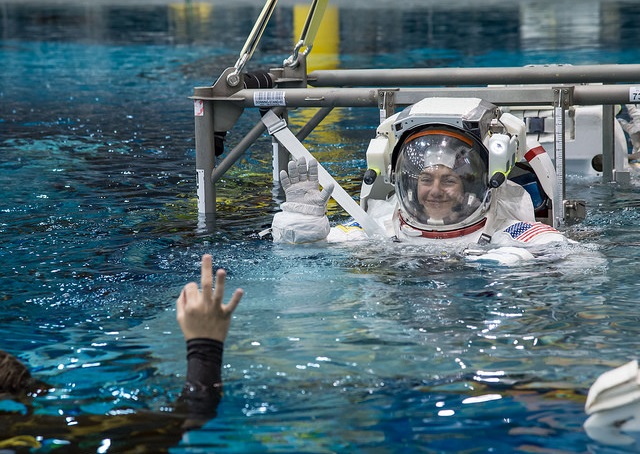

The second skill set is learning how to use the space suit in NASA’s giant pool, where they have an underwater mock-up of the space station. “Learning how to use the space suit is the most challenging thing that we do,” Meir said. “It’s just unlike anything that you’ve ever done before … You weigh over 400 pounds in the suit; it’s pressurized, and everything you do is like squeezing an exercise ball. So it’s really the most challenging thing we do – but it’s also one of the most rewarding, and one of my favorite things to do.”

After all, she added, “A lot of people get to fly jets, but when you’re in the space suit, you really feel like you’re an astronaut.”

The third skill is “learn[ing] all about the different systems on board the space station, everything from the power and electrical system to the thermal control system to the life support system. When we’re up there, we need to operate all those things and also need to know how to fix them if they break.” (Anyone who saw The Martian knows why this is crucial.)

The fourth skill is learning to fly the International Space Station (ISS) robotic arm. “The Canadian space agency built this robotic arm on the space station that we use to reconfigure different elements on the space station,” said Meir. “We use it on space walks, that kind of stuff. That’s actually flown by a person inside the space station.”

The fifth and final area is Russian language training. “Everybody on the space station speaks both English and Russian, since it’s an international space station. It’s not just us; it’s also the Russians, the Japanese, the Canadians, and the European space agencies.”

Analog Training and “Expeditionary Skills”

In addition to the standard two-year training, NASA astronauts and scientists can go on rarer missions to what are called analog training environments. “How do we train for what it’s like in space?” Meir explained. “We can’t replicate everything about space here, of course, but we try to find environments on earth that replicate some of those characteristics. So, for example, if you have a situation where a group of people is living in an isolated, confined environment, where you need a life support system, and you’re functioning together as a small crew with an overall mission objective – that has a lot of similarities to space flight.”

These trainings are most helpful for what NASA calls “expeditionary skills.” As Meir explained, “One of the things that’s really important is just learning how to play nicely with others. You’re going to be in space for six months with someone in a small, confined space. Who wants to do that with someone that’s a jerk? So we do a lot of these things in order to learn more about ourselves, learn more about our teammates, practice how to be a good team player, how to take care of yourself, how to take care of your team, leadership, followership … These environments are really great training for especially those aspects.”

Meir has been on two of these analog trainings: one in an underwater habitat, and one inside a deep cave in Sardinia, Italy.

In the NEEMO (NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations) Project, participants live in an underwater habitat off Key Largo called Aquarius. “Like space, you’re living with a small crew in a confined space; you need a life support system to go outside because you’re underwater; you have training objectives, scientific objectives, that kind of thing. So it’s a really valuable experience for us, especially in expeditionary skills.” Meir originally took part in NEEMO when she was working at NASA as a scientist, sharing the habitat with two astronauts, a flight director, and the habitat technicians.

As an astronaut, Meir participated in CAVES (Cooperative Adventure for Valuing and Exercising), a two-week analog mission run by the European Space Agency, in which astronauts from all over the world live in a cave in Sardinia, Italy. Meir’s own mission was with one other NASA astronaut, a Japanese astronaut, a Spanish astronaut, a Russian cosmonaut, and a Chinese taikonaut.

“That was probably one of the most extraordinary things I’d ever done in my life,” she said. “It was really amazing. You’re wearing a harness all the time, because you might be lowering yourself down like a 25-meter shaft. Or you’ll be squeezing through a tiny little passage, and then the next thing you know, you’ll come out into this giant gallery with like a 100-meter wall. It was just extraordinary. We felt like characters in a science fiction illustration. It was unlike anything I’d ever seen, or knew existed on Earth. You kind of felt like a character in The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings. It was just that extraordinary.”

“We even used to say that if we put space suits on and filmed this, we could convince people we went to another planet,” she added.

As the analog missions show, the psychological aspect of space flight becomes more and more important the further we want to go. Long-duration missions are emotionally draining, involving a lot of isolation and sharing confined spaces with strangers from other countries. As a result, the mental health elements have even become part of NASA’s selection criteria.

“Since we’re doing these long-duration missions now,” Meir explained, “we are really only picking people that are capable of that, and so there’s a lot of psychological screening just in terms of selection.”

In addition to the initial screening, NASA runs these expeditionary skills missions to prepare the astronauts. “We try to emphasize these things through programs like the analogs I mentioned, or through backpacking trips as a team, and lots of different teamwork-type activities,” said Meir. “Those are really focused on this psychological aspect – you know, living and working in an isolated environment, being part of a team, being a good crew member, taking care of yourself, living in isolation. All of those analogs, and then these other training opportunities, are focused on those skills.”

NASA also works to protect the mental health of those who are in orbit. “We have a really good psychological support group here at NASA, too,” said Meir. “Even on the space station, they make sure that they arrange family conferences on a regular basis; you’re getting care packages – stuff like that, to keep you psychologically motivated and healthy.”

(Featured image via NASA/Bill Stafford)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com