Our Books, Our Shelves: Juneteenth and Freedom

For the past few years, while writing a speculative novel trilogy, I’ve been residing for much of the time in the future, in a fictional place known as the Disunited States of America, where a plantation-inspired system holds sway in a wide swath of the country.

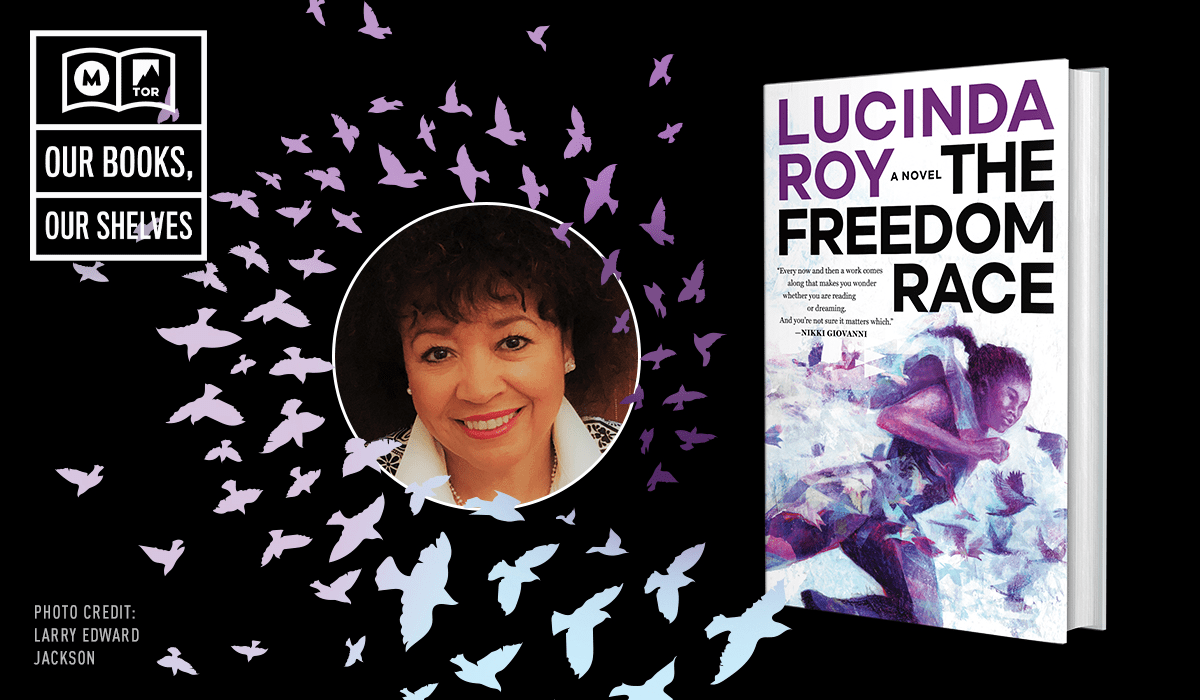

As we near Juneteenth and think about the nature of freedom, and how difficult it is to establish an equitable and just society, one of the things that worries me is this: the future world I imagine in The Freedom Race seems a lot less far-fetched than it used to be.

Juneteenth holds special meaning to those of us whose forebears were taken from Africa and sold into slavery. More than one hundred and fifty years ago on June 19, 1865, Galveston, Texas learned that the enslaved had been emancipated. Freedom was theirs for the taking … but not really. The news was more than two years late, Abraham Lincoln having issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan 1st, 1863. It would take the U.S. another century to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Even now, more than fifty years later, the journey toward racial equality is far from over.

We are witnessing the most significant re-examination of race relations in this country since the 1960s. Recent events—the insurrection of January 6, the murder of George Floyd, the move to limit voting rights and thereby curtail democracy, to name only a few—suggest we are not only a country divided, we are a country flirting with implosion.

In my novel The Freedom Race, the first book in The Dreambird Chronicles trilogy, climate insecurity, pandemics, a second civil war (simply called the Sequel), and social unrest have fed a secessionist movement. Inside the once-great nation, rural areas have split from urban ones, and much of the country’s Old South and Midwest regions have severed themselves from the two coastal SuperStates.

Jellybean “Ji-ji” Lottermule, with her friends Tiro, a cage flyer, and Afarra, an outcast, live in the secessionist Homestead Territories in a rural region of the former Commonwealth of Virginia. Classified as a “botanical Muleseed,” a non-certified human, Ji-ji’s only chance to escape is as a runner in the annual Freedom Race.

The horrors of slavery have been well documented. But there is also this. Against all odds, the enslaved survived. In the stories they told each other, they refused to forget what it meant to be human. They dared to sing, and dance, and love; they dared to plant the seeds of hope in the belief that the arc of the moral universe, as the Reverend promised, would bend toward justice.

When I first conceived of The Freedom Race, the idea that there could be a second civil war seemed unlikely to most people. We had a biracial president in the White House, and especially for those who had never experienced prejudice, racism appeared to be on the decline. But the more I entered the world of the novel the more I realized that the concept of a post-secessionist Disunited States wasn’t nearly as implausible as I wished it to be.

Novel writing, whether it be speculative fiction or mainstream literary fiction, is driven by character, so I didn’t write The Freedom Race simply as a warning about what could happen if the deep cultural fissures we are experiencing today are allowed to fester. I wrote it primarily because the character of Jellybean “Ji-ji” Lottermule took up residence in my head and wouldn’t move out.

Dismissed as plain and disposable, Ji-ji refuses to accept the limitations placed on her by the father-men on the planting where she’s been raised in captivity. Even before she discovers a wondrous secret her people carry, she is determined to “make herself” and not let others make her. It seems to me this is the quest of courageous women of all ages everywhere. It’s why women’s voices must be heard during this time of dangerous, premeditated aggression.

Ji-ji Lottermule’s story is not only a story of suffering, it’s also a story of wonder and magical realism. As time went on and the novel series came together, other characters—black, brown, and white—joined her. Eventually there was a multiracial chorus demanding freedom and clamoring to be heard. I realized that the story I was writing wasn’t simply a narrative about slavery, it was a story of survival and transformation.

Like Juneteenth, survival narratives are celebrations of the triumph of the human spirit. In The Freedom Race, something miraculous occurs in the middle of the narrative—something with the potential to change everything. This transformational change draws upon an enslaved people’s collective memory and the powerful stories they tell each other. Like all hope during times of struggle, it demands a leap of faith.

For me, stories about the future work best when the far is made near, and the near is made nearer. I didn’t write The Freedom Race because I wanted to imagine the future, I wrote it because I wanted the future to re-imagine us—to reveal something we may not have understood about ourselves before. I also wrote it because I was dealing with unimaginable grief and loss, and I needed to find something to give me hope. I hadn’t expected to find it in a young, enslaved girl from a deeply troubled future, but that is what happened.

Writing an honest narrative about slavery is hard. As I wrote in the Author’s Note at the beginning of the book, the most deep-rooted hope is honed by suffering, and oppressive systems premised on prejudice demand an honest depiction. No surprise, therefore, that the series contains raw and challenging subject matter. But in the spirit of Juneteenth, I wanted to write a story that celebrated enslaved people’s determination not simply to survive but to overcome.

Get your copy of The Freedom Race here.

- About the Book:

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope.

The second Civil War, the Sequel, came and went in the United States leaving radiation, sickness, and fractures too deep to mend. One faction, the Homestead Territories, dealt with the devastation by recruiting immigrants from Africa and beginning a new slave trade while the other two factions stood by and watched.

Ji-ji Lottermule was bred and raised in captivity on one of the plantations in the Homestead Territories of the Disunited States to serve and breed more “muleseeds”. There is only one way out—the annual Freedom Race. First prize: freedom.

An underground movement has plans to free Ji-ji, who unknowingly holds the key to breaking the grip of the Territories. However, before she can begin to free them all, Ji-ji must unravel the very real voices of the dead.

Written by one of today’s most committed activists, Lucinda Roy has created a terrifying glimpse of what might be and tempered it with strength and hope. It is a call to justice in the face of an unsettling future.

- About the Author:

Lucinda Roy is an award-winning novelist, poet, and memoirist, and a lifelong advocate for diversity and inclusion. She has lived and taught on three continents and is recognized for her keynotes on race and gender, creative writing, and education reform. Her commentaries and poetry have been published in numerous newspapers and journals, including USA Today, the Guardian, and the New York Times. She lives in Blacksburg, Virginia, where, as a distinguished professor, she teaches creative writing at Virginia Tech. For The Freedom Race, she relocated to speculative fiction because it allows her to imagine what form hope would take inside a damaged future world.

Don’t forget to check out the other excellent additions in our exclusive Our Books, Our Shelves column with Tor Books!

- A.K. Larkwood & Tamsyn Muir in Conversation, by A.K Larkwood and Tamsyn Muir

- BE A QUITTER, or HOW TO WRITE THE NOVEL OF YOUR HEART, by K.M. Szpara

- Down with Literary Snobbery, Long Live Genre, by Sarah Kozloff

- Bestselling Author John Scalzi Talks the End of Everything with John Scalzi

- A Billion Thoughts at Once by TJ Klune

- RIP, IRL: Fandom Has Always Lived Online by Camilla Bruce and Kit Rocha

- Alaya Dawn Johnson on Writing and Book Advocacy with Alaya Dawn Johnson

- On Persistence, Nearly Giving Up, and Writing On by Martha Wells

- The Piss Problem: The Politics Behind Peeing in Space by Mary Robinette Kowal

- What Can Gender Swapping in Stories Tell Us About Ourselves by Kate Elliot

- An Exclusive First Look Behind The Scenes of Bestselling Author V.E. Schwab’s New Novel, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue with V.E. Schwab

- A Celebration Of Chaotic Good with Andrea Hairston, S.L. Huang, S.A. Hunt, and Ryan Van Loa

- The Fallacy Of The Universal by Mark Oshiro

- Bookish Activism & Rejecting Fatalism In Favor of Hope by Cory Doctorow

- Go To The Bookstore With V.E. Schwab, Bestselling Author of The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab

- Christopher Paolini’s Love Letter To Sci-Fi by Christopher Paolini

- Come For The Worldbuilding, Stay for the Character Development: Brandon Sanderson’s Rhythm of War

- History is Quicksand, Stories Are What I’ve Got by Nghi Vo

- Art in the Year of Calamities by Jenn Lyons

- Sarah Gailey on Putting Yourself Into Your Characters by Sarah Gailey

- J.S. Dewes and Karen Osborne in Conversation

- An Exploration of Show and Tell by Marina Lostetter

- Crafting Your Own Reality by Nghi Vo

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com