Review: Gail Simone’s Leaving Megalopolis and (the Blessed Lack of) Sexual Violence

In Gail we trust.

Gail Simone seems to like surprising readers, from bringing new female audiences into the world of Red Sonja to infusing her Futures End one-shot for DC with a message of hope and female friendship. I originally missed out on Leaving Megalopolis, the graphic novel that reunited her with Secret Six artist Jim Calafiore, because the 2012 Kickstarter came just when I started really getting into comics. Thanks to the Kickstarter’s success, Dark Horse reprinted the books as hardcovers last month. I couldn’t resist nabbing myself a copy, and it surprised me. Because Leaving Megalopolis manages to be a story of heroes gone bad with bloody ultra-violence… without doing the things that make me crazy and drive me away from those kinds of stories.

Warning for minor spoilers throughout.

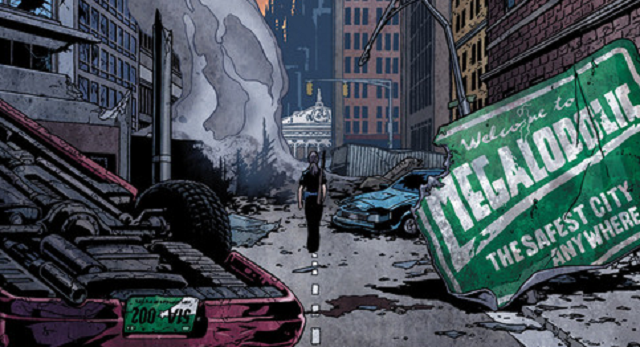

The story is mostly set in Megalopolis, a city hailed as “the safest city in the country” thanks to being the home of a slew of various superheroes. However, a… thing happens that makes all the superheroes snap. Now the entire city is under attack by the very heroes they had come to trust, and a small band of civilians must make their way to the city limits and out of Megalopolis through one of the city’s few exist.

The book is about terrorism in the most basic definition of the word. Beings with immense powers start using those powers to slaughter most of the civilians and then terrorize those that are left. Most are playing with their prey for fun, while others are filled with spite and make sure to tell their victims they should have been more grateful right before they set their fellow citizens on fire. In some ways, it’s a genre successor to Watchmen. While the plots and even the ultimate messages of the books are very different, a lot of what I like about Leaving Megalopolis is a lot of what I like about Watchmen. In both canons there’s a focus on a history of in-universe morally good costumed heroes, a sense that the heroic ideal has been shattered and left with cold, ruthless reality. They both use flashback as well as in-universe media to strategically break up the scenes and give depth to their world. Both books question what being a hero means and feature a hodgepodge of diverse non-costumed characters who find a connection in tragedy (only Moore’s characters find it in the very last seconds before disaster, and Simone’s find it in disaster’s aftermath). There’s also the matter of both stories involving giant tentacle monsters, so make of that what you will.

There’s a lot to like in Leaving Megalopolis, including Simone’s sharp dialogue, the diverse group of survivors, and the dense world-building that’s accomplished in a short number of pages. There’s also the complexity of main protagonist Mina, whose police uniform makes her the leader of the travelers by proxy. Mina manages to be both hard edged to her companions and extremely vulnerable in the eyes of the reader thanks to the use of flashback. Scenes of her childhood weave in and out of the story, slowly informing us as to her motivations and why she reacts the way she does to each member of the traveling group. There are several parallels made between the events unfolding in the present and the domestic abuse in her past, to the point where the current reign of terror by the “heroes” can be seen as a metaphor for domestic abuse—someone who is supposed to respect and care about you not only turns on you but blames you for it. I doubt it’s a coincidence that the first “turned” hero that Mina sees kill people uses techniques similar to what her father used to torture her mother.

The message I got most out of Leaving Megalopolis was the suggestion that bravery comes in many different forms. Sometimes it’s standing up alongside others. Sometimes it’s living through trauma and being able to get out of bed each morning. This past weekend at NYCC, when our own Editor in Chief Jill Pantozzi interviewed Simone about her just-announced new horror comic Clean Room, Gail spoke on the appeal of resilience in her stories: “There’s a lot of heroism in just surviving, sometimes.” And that’s pretty much what Leaving Megalopolis is about—the courage it takes to endure and keep walking.

But the thing that had me sort of amazed was an element that I wish wasn’t so rare: how well it treated the female characters. Now, that doesn’t mean women are spared from being killed–women are killed in this comic. The travelers see women get killed first hand, and they come across women already dead in the street. But unlike a lot of other dark, “adult” graphic novels, the women’s deaths aren’t exploitative. There’s no oddly sexual body language from women as they are shot. The corpses of women (including a particularly effective panel of bodies lined up as a warning for those thinking of taking one of the bridges out of town) are just as clothed as their male corpse counterparts. There’s one shot early on of a dead woman in her underwear, but there is nothing sexual about her pose or even the underwear itself—the bra is practically utilitarian. Another scene has a younger woman huddled in an abandoned store, and while she only has clothes on from the waist down, the way she’s drawn doesn’t suggest sexiness—she’s just exposed and scared.

There’s never a sense that the creators are trying to entice you with pseudo female sensuality to seem “edgy.” The pervasive male gaze is nowhere to be seen. Kudos go to Calafiore for avoiding the kinds of inappropriately sexual visuals that so often get me frustrated as a comic reader. Heck, the only time we see a character’s breasts in the whole book is during what might be the briefest, least exciting sex scene in all of comics (and kudos to colorist Jason Wright for the use of shadows to downplay the nudity in that particular moment).

Beyond the lack of male gaze, the main plot is also devoid of any gender-targeted violence. The violence is brutal and gory, but there are no attackers pulling women’s hair so that her back arches and her breasts push out, no women getting threatened with rape, and no evidence that women are being targeted as “good fun” murders over men. One of the most memorable female deaths is actually a head-shot, and it’s chilling in its simplicity. The only place a woman is targeted for violence because she’s a woman is in the flashbacks, and even then Simone and Calafiore frame the violence very carefully. As I said before, our protagonist of sorts grew up in a home with domestic abuse, but when we finally see the abuse, it focuses more on the victim (the actual violence isn’t shown in-panel). Like the deaths of women in the present, the violent nature of the husband towards his wife is not romanticized or meant to excite the reader. The panels are drawn so we’re seeing the scene through the victim’s daughter’s eyes—like in the rest of the book, there is no male gaze in this scene.

Simone also makes sure to give the victim a moment of courage, and that memory her daughter carries (both the mother’s resilience in the face of her abuser and the abuser’s reaction) directly affects our main character’s understanding of the world. She carries the shadow of that trauma and sets up her choices as she finds herself face to face with her own protectors-turned-abusers in the form of the former heroes. Your mileage may vary on how effective and respectful to real victims a story is when it includes a scene like this, but I personally felt this is one of the better examples of how to include violence against women in comics without cheapening the trauma real women experience.

Sure, you can make the argument that showing sex crimes against women during the main plot would have highlighted the danger and darkness of the setting, but I was relieved it wasn’t included. Reading these kinds of books (the ones marketed as “dark and gritty”), I always brace myself for the inevitable “violence against women to prove it’s a bad place” scenes. Watchmen itself certainly had them (not just the Comedian’s near-rape of Sally Jupiter, but also the barely touched upon gruesome murders of both lesbian vigilante Silhouette and the unnamed pregnant Vietnamese woman). The Sin City books (and others in the noir genre) have them. Selina’s side quests in the comic-inspired Arkham City game have NPC thugs constantly discussing how they’d like to “teach Catwoman a lesson.” And don’t forget how many grim action movies have a love interest assaulted or tortured, with lots of camera pans up her body.

Somehow, it always comes down to women being punished for being women in a violent environment, with the excuse being that “it’s realistic” and therefore necessary to write the story that way. However, I see it as a conscious choice by creators. Realizing that a story has cheap “sexy violence” for grit’s sake makes me not want to finish reading it. And yet here’s Leaving Megalopolis, a so-called dark book perfectly capable of convincing us the city is an absolute hell on earth without having a woman be raped by a former hero or a corpse conveniently posed like a pinup. Imagine that. It can be done. And I happened to like the book so much more for not pulling punches.

The book isn’t perfect. The side plot of upper crust apartment residents going Lord of the Flies felt like a cautionary story I’ve seen played to death already, and the gore goes over the top nearing the point of silly at times (take, for instance, the very first in-panel kill involving a manic, bloodthirsty speedster literally messing with a guy’s head). But the book took a gritty, grim dystopia of a city and showed that world to its readers without the exploitation of female characters that so often gets used in this particular setting. It just also happens to be a compelling read, too.

Katie Schenkel (@JustPlainTweets) is a copywriter by day, pop culture writer by night. Her loves include cartoons, superheroes, feminism, and any combination of the three. Her reviews can be found at CliqueClack and her own website Just Plain Something, where she hosts the JPS podcast and her webseries Driving Home the Movie. She’s also a frequent The Mary Sue commenter as JustPlainSomething.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com