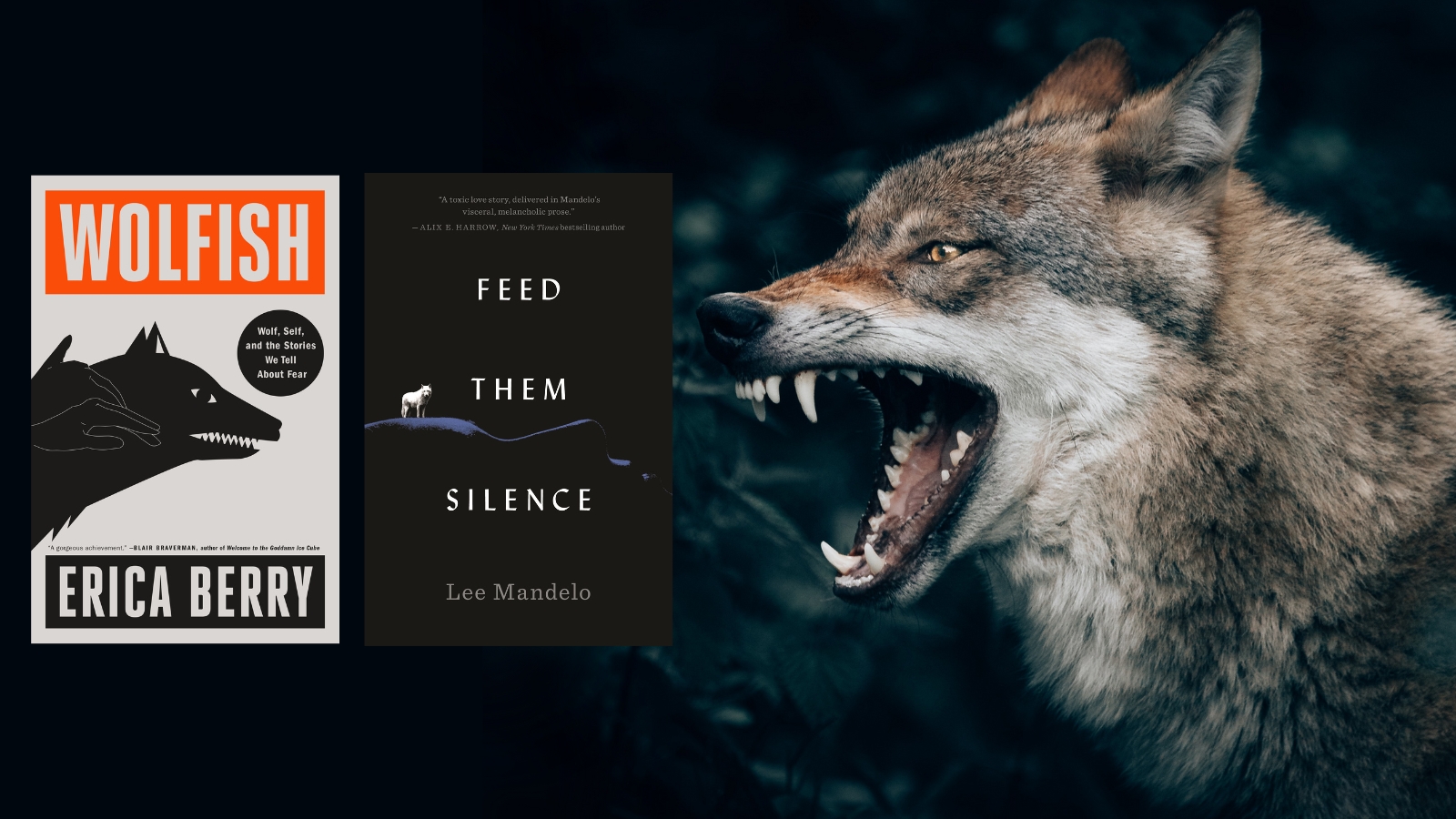

Lee Mandelo’s ‘Feed Them Silence’ and Erica Berry’s ‘Wolfish’ Obsess Over Wolves & Connection

From childhood, we’re taught to fear wolves—perhaps not directly, since these pack animals only live in certain territories, but through stories for certain. Whether it’s ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ or ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf,’ we’re taught that wolves are dangerous to humans.

Erica Berry’s new nonfiction book, Wolfish, examines the relationship between wolves and fear, as well as how she relates to them as an individual who’s never encountered a wolf in the wild. Lee Mandelo’s new science-fiction novella, Feed Them Silence, examines one woman’s relationship with wolves in a near-future world wherein there’s only one wolf pack left in the contiguous U.S. Both books find their central thesis in an obsession with wolves, whether that presents itself as a fear of them or as a desire to run into the woods and be in community with them.

Whatever our relationship with these creatures, wolves seem to occupy a huge space in many imaginations, which we attempted to unpack with Mandelo and Berry in discussions about their books.

Although Mandelo’s novella is science-fiction, his representation of wolves says a lot about how we interact with these animals in our imaginations. The main character in Feed Them Silence, Dr. Sean Kell-Luden, is a married lesbian at the top of her field, and she’s developed a neural implant that will allow her to experience the world through the mind of a real wolf. In the process, she becomes increasingly obsessed with this wolf and her pack, which puts her life, relationships, and career at risk.

“I was—as I think many strange queer children were—super into the ’90s wolf books. There were truly so many books about going off into the wilderness to be part of a pack. That was the whole thing,” Mandelo tells The Mary Sue. “And it makes sense in hindsight why a child would be really into that. It’s like, ‘I don’t fit in socially. Maybe it would be better to just be in the wilderness.'”

Mandelo drafted Feed Them Silence in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when he was enrolled in a seminar for his doctorate about social theory on animals. As part of the class, Mandelo read an essay by Staying With the Trouble author Donna J. Haraway.

“[It] was about animal cognition and our fantasies of being able to know the inside of another person or another creature, and how we are also animals with those animals. She’s talking about her pet dog in it and that those relationships are necessarily ethically complicated but also beautiful. They can be many things at once,” Mandelo says. “The interviewer asks her, ‘Have you ever wanted to know what he’s thinking?’ Her answer really did something to my brain because [she said] that fantasy is violent. There is something inherently violent about wanting to be able to fully know the inside of any other creature. You don’t even know fully the inside of yourself. So you’re kind of presuming a colonialist mentality that you can take it apart and study it and know it, and our protagonist in Feed Them Silence does think that.

“Most western—particularly American—funded science at the moment, especially on animals, biology, and climate is pretty destructive a lot of the time. We see the world that we’re living in as it falls apart ecologically, right now, in this moment. So I kind of wanted to look at why we’re failing,” he continues. “It’s that fantasy of, ‘I don’t really wanna help, I just wanna know.’ I own that knowing and what that does to you and the wolves. So I both love wolves and ask, ‘What is questionable about my love for wolves?'”

Ultimately, our relationships with animals are parasocial, which makes them difficult to reconcile.

“I’ve been thinking a bit about something a rancher told me, which was that wolves are like ghosts, where you just hear them but you’re not actually seeing them. It makes me think of the people that I would have crushes on early on: [they] were not the people I had interactions with. It was people I didn’t really know, and you’re just sort of visualizing that,” Berry tells us. “And I think there’s something about the wolf—there’s like these breadcrumbs where they become the distance. Nabokov has a quote: ‘Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story, there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.'”

Developing these one-sided relationships may feel to the person in question like they are expressing care for a person or animal, or that they are establishing some kind of intimacy. In Feed Them Silence, Sean gets so lost in her own obsession with “her wolf” that she begins to ignore the science and imagine something emotional between them.

“I think there’s something about the idea of being a human animal that appeals, but we’re kind of not allowed to do that socially, usually in that very Cartesian dualism, mind/body, ‘We gotta be above that body’ [way]. But queer people are pretty in our bodies. And especially if you are disabled or you have chronic pain, things like that, you’re very in your body in a way that only animals are supposed to be,” Mandelo says. “Our connections make way for a lot of people to identify, not just with animals because that’s a whole thing, but with the structure that we see of a wolf pack.”

Sean gets so immersed in her desire to understand wolves that everything else begins to fall apart. Mandelo remarks, “I think that she goes so far off track here, that the only connection with her own body that she’s experiencing is when she is neurally connected with this wolf. Her relationship with her partner is falling apart, her relationship with her coworkers is falling apart. And I also think that her relationship with herself is falling apart.”

Mandelo also notes that Sean’s self-imposed isolation is partially inspired by the forced isolation of the pandemic, which we have all experienced to varying degrees since it started.

“Sean entered STEM and is a very masculine presenting person, which I also am, so I’m kind of looking at that critically in some ways. Everyone can try to join the patriarchy. Anyone can give it a shot. And there are a lot of ways in which she has done that because it is part of the field. It’s part of that assimilation into a certain structure of science and funding that’s not really interested in the ethnography of it all or the equality with another species. It’s just kind of taking it apart without that care,” Mandelo says.

“Part of her disconnection from herself is having been in that field for so long, and that’s also part of the pandemic isolation of realizing how important all those connections are. I think the experiences she has throughout the text make her reflect more on how disconnected she is from herself and her partner and all the other people in her life. But that’s not always enough to make a person change. Sometimes you just see it, and you’re like, ‘Wow, fuck.’ And then you don’t do anything about it because it’s very difficult to do. I think that kind of darkness of it was part of my response to the pandemic,” he continues.

Feed Them Silence is not a feel-good romp. The deeper Sean gets, the darker her life becomes, and the end of the book explores the consequences of her selfishness. Mandelo’s approach to talking about the patriarchy and capitalism in his novella is to do so through the eyes of a queer woman who’s assimilated into those systems as much as possible in order to do what she wants, when she wants with her research.

For Berry, a heterosexual, cisgender white woman, researching and writing Wolfish has completely altered her relationship to these creatures in a much more community-centered way. Joe Whittle, a photographer and writer who’s also an enrolled member of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, has been talking to Berry for the last decade about this book. Berry recalls him saying, “Capitalism makes the wolf a wolf.” This reminded her of how, in her research, she learned that in 1873, the Japanese government hired American rancher Edwin Dun to help them build their livestock industry and kill off a local wolf population that threatened their plans.

“Who the wolf is depends on these structures around it. Joe can be really empathetic to some of these livestock producers who have been really vitriolic toward wolves. And he was like, ‘The fact is that their margins are so low and there are all these other things wrong with the livestock industry that makes the wolf such an easy target. How could we create a more equitable way of creating food so that the wolf would not be a threat?'” Berry says. “I’m interested in debates around reforming the food system and wouldn’t have thought that learning to live beside this wild creature and learning to think about how we could have more sustainable, more equitable food practices—there’s some connection there.

“I do think that I’m somebody who tries to believe in hope despite all the odds, so as things are getting very bad during the pandemic and a lot of producers are struggling, maybe there’s a breaking point where something better comes out of that,” she continues. “Deb Holland at the Department of the Interior and all of the ways that people are beginning to understand in the west that maybe Indigenous folks should be in control of this land feels like very hopeful steps. There’s been so much of that recently that I do feel like that gives us a new vision for living beside the wolf a little bit.”

In learning about wolves, Berry was also able to restructure her relationship with fear. “For a while, I was obsessed with this question of how people were better at being mortal, I guess, than I was,” she explains. “I felt like I was really anxious about everyone around me dying. The wolf became a thing where people are looking at the wolf and they’re bringing a lot of irrationality to their fear. I felt like I was irrational in my other fears, so I wanted to examine that middle ground of deciding if you’re right to feel that fear. I think there was something therapeutic about that process.”

For Mandelo, learning about the family structure of wolves reinforced his relationship with them, as a queer person who was fascinated by the idea of pack life as a kid. He says, “Thinking about family structure in wolf packs is also really queer, which was something that I kind of already knew. That’s why we’re all attracted to the idea of the pack structure anyway. It’s kind of like a chosen family, it’s got weird hierarchy, whatever. But then the more research you do, you’re like, ‘Oh, it really is, though.’ There are just some parents and then a bunch of sometimes related, sometimes unrelated other wolves who just like each other and hang out. And if someone’s a jerk, sometimes they get kicked out. That’s it. And it’s kind of nice.”

Feed Them Silence and Wolfish are both available everywhere books are sold.

(featured image: Flatiron Books; Tordotcom; Philipp Pilz / Unsplash / The Mary Sue)

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com