In Mirai, Mamoru Hosoda Uses Fantasy to Capture the Tender Dynamics of an Everyday Family

Movie-families are entertaining, but the medium often demands certain one-dimensional notes: perfect, static characters, the promise of everything being fixed forever, or exaggerated conflicts. That’s not to criticize these stories, which are wonderful and heart-warming and cry-worthy in their own way, but to draw attention to how skillfully and tenderly Mirai is able to draw you into the world of its characters.

The film Mirai begins with our protagonist, the little boy Kun, waiting at home and playing with his trains. When his parents come home, they present him with his new baby sister Mirai (meaning “future”). It’s a glorious occasion, but not one without struggles. His mother goes back to work while his father runs the household at home, and Kun grows increasingly jealous of his little sister. It turns out, that even happy changes require some adjustment.

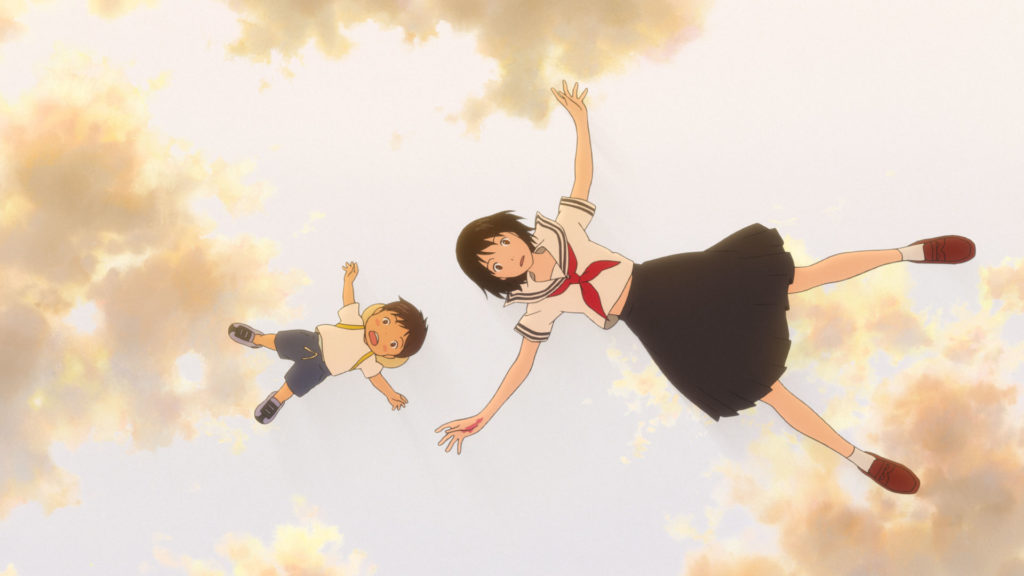

The story is punctuated with regular outbursts by Kun, and the realism isn’t surprising considering director Mamoru Hosoda took inspiration from his own family. The family dynamic is a familiar one for anyone who has had a sibling, but Hosoda, the Studio Chizu director of Summer Wars, Wolf Children, and The Girl Who Leapt Through Time adds a fantastical element to the story: Kun, after his tantrums, begins meeting figures from the past and future. His sister Mirai (suddenly a teenager), his deceased grandfather, and other relatives all meet him in interactions that allow him to better understand his own family’s story.

Mirai is a film that is interested in the intimacy of families in their everyday lives, and the result is tender and heart-warming. Through these time-travel journeys, Hosoda reminds us that our families are constantly growing and changing. Sometimes these changes occur in obvious ways: a death in the family, a marriage, or a birth are all big landmark events that we commemorate and carve into our collective memory. Other times, they’re changing simply because time passes. There are countless moments that seem completely inconsequential in the moment, that later become defining moments for our character and our relationships with others. It’s also a frank portrayal of childhood and childishness.

In Mirai, Hosoda demonstrates that the mundane and the routine are just as worthy of our time as the dramatic and exciting—don’t worry though, the movie has both. I spoke to director Hosoda over email about his approach to creating a family that could be both loving and flawed, understanding childhood, and his ability to mix the fantastical with the familiar.

I think it’s interesting that while the story is mostly from Kun’s perspective, there’s still a lot of time spent with the parents. Were you consciously trying to make a film that both parents and children could relate to?

Normally when you make a child a protagonist, parents tend to become antagonists. Like if the child is justice, the parents are portrayed as people who restrain the child or take away their freedom. Or that they are only a small part of the whole story. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to depict both as imperfect humans who will grow and change. And even the topics that the parents talk about…in normal anime films, they have perfect parents who only think about their children, but in this film they are just like us.

They talk about their children, but also about work, and their personal life. They have many things to juggle. To depict realistic parents like that was an important part in the storytelling of this film, also in a sense of using animation as a form of art.

In relation to the parents, you’ve showed different kinds of families in past films like The Boy and the Beast and Wolf Children. This time, it’s a couple that has switched roles in the household—tell me about why you chose this family dynamic to explore?

The fact that the father staying at home to watch the children is getting very common in Tokyo right now. Perhaps 6 years ago, you wouldn’t see many fathers carrying their babies around. But now, it doesn’t even stand out. So it’s not like I was trying to put in a message in this movie, but it’s a fact that’s happening right now.

I think the current state of “what a family is” has changed from what it was before. Families are trying to figure out how they should be as a family without conforming to old standards.

With films like The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, you’ve skillfully integrated fantastical stories and premises into these very relatable characters from every-day life. What is your strategy when combining these two worlds?

I think others tend to do fantasy films for the sake of doing fantasy. They want to create a fantasy world, and because of that they make the focus on the characters secondary or nonexistent. I look at that and think that one’s priorities are backwards.

I like to use fantasy as a tool to understand what life is about. To depict the true nature of people. For example, you can use fantasy to portray humans in a way where you won’t get to portray if they lived normally. Then you can see a person’s true intent, and even beyond that, their raw soul. I believe that is what’s important in a movie. And to do that, I use fantasy. Perhaps that is why you say kind words that I have skillfully integrated the two elements.

You’ve said that the film is somewhat biographical, and that you were inspired by your son’s tantrum. Do you feel like you learned something about children and growing up by making Mirai?

Normally we think that our memories as a 4 year-old have faded. But it’s not true, it’s there, and you can remember them as long as they are triggered. And I was able to remember my memories as I interacted with my children. And as a result, I am able to relive my childhood. I think remembering how you felt when you were a child is important when communicate with your children. And I realized how important childhood was when making Mirai. When we grow up, because we forget our childhood, because it’s forgotten we tend to think that it wasn’t significant or important. But that’s not true. Childhood—especially when you’re about 4 or 5 years old—is when you have so many first experiences. And how you live through those experiences change the way you live your future. That is what I learned.

I thought the scenes with Kun’s great-grandfather were really beautiful—that it showed how even when someone is no longer alive, their life is still linked with yours and important to learn. Can you talk a bit about that storyline, and what you were trying to say about family connections?

When my son was younger my wife’s grandfather—my son’s great grandfather—passed. When that happened, I was sad because I was hoping for him to teach my son many things. And when I looked at old pictures of him—he also had a bad leg like the great grandfather in the movie—he was on a motorcycle, posing. And I thought what kind of past he could have had.

A little bit after that, my son suddenly learned how to ride the bike. I was really surprised, thinking that maybe someone else had taught him, or maybe that his passed great-grandfather had taught him. That is where I got the idea of that storyline.

Mirai comes to theaters starting November 29th. You can check out more GKIDS details here.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com