What Makes Novels So Uniquely Relatable?

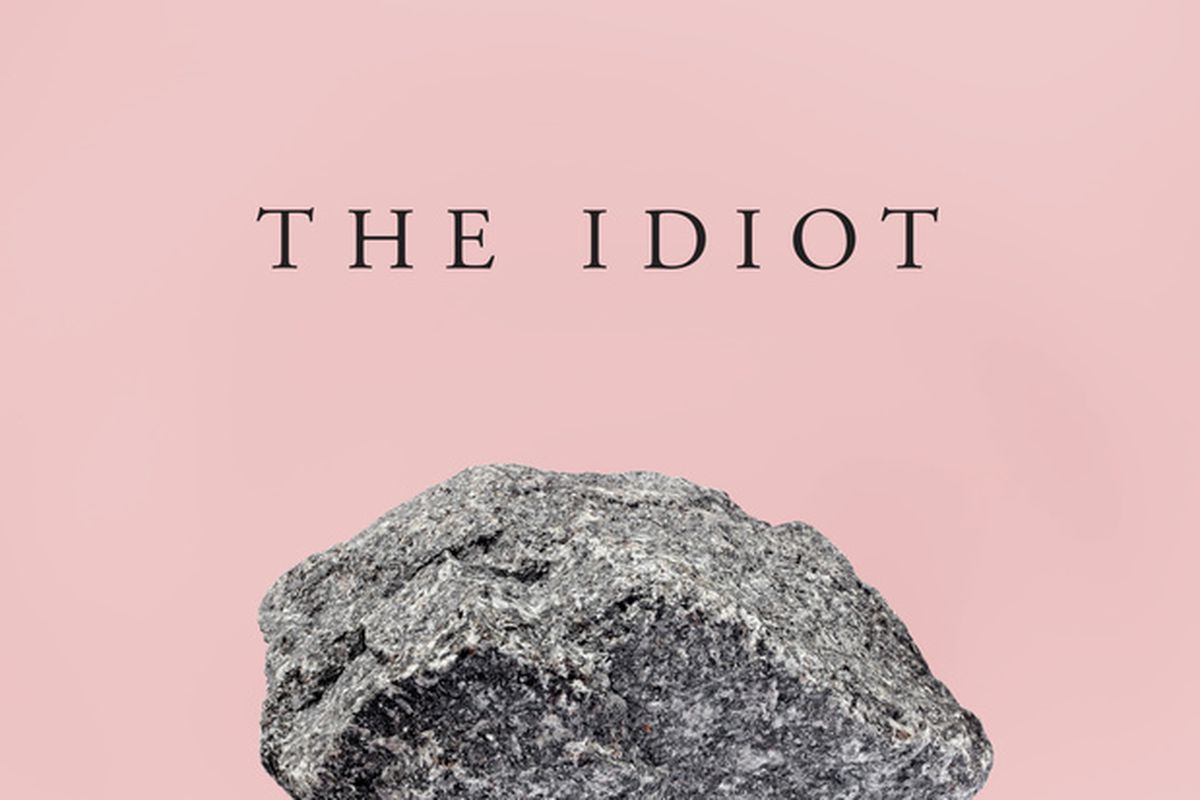

For years, I put off reading Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, because I was tired of “nerds” and nerd culture. I’d grown up in a protective and sheltered household, surrounded by people with a similar upbringing, and yearned for new experiences, things that would throttle me headfirst into “adulthood.” Conversely, the protagonist of Batuman’s debut novel, Selin, seemed to be the person I feared I’d become: an overly-analytical ingenue, book-smart but lacking in street smarts.

Ironically, now that I’ve actually read the novel, I found that I couldn’t get enough of Selin, because she did, in fact, remind me a lot of myself when I was an underclassman, which made it an intensely warm, yet frustrating experience. I wanted Selin all the time, thought about the book when it wasn’t on me, yet when I’d actually sit down to read the book, I’d find myself saying out loud, “Girl, get a grip!” As soon as I finished it, I devoured its recently-released sequel, Either/Or, and was even more enchanted with Selin, who’d grown into a much more emotive and expressive person. And when the book was done, and we said goodbye to her at a Russian airport, I felt incredibly sad. I wanted more.

That’s the beauty of a good book, as clichéd as it sounds. I know we’re all told that reading is good for you, yada yada, but Selin’s journey really made me question the ins and outs of why. After all, I’ve been touched by video games, music, movies, and art alike, yet nothing pierces my heart quite as much as a really good book. It’s why I have such a hard time reading consistently: I’ve experienced this feeling enough that my disappointment with a mediocre book is almost too much to bear.

But what makes novels such personal experiences, so much so that they stand out from other forms of media? In short: They’re a simple conversation between the reader and the narrator, and nobody else is allowed inside.

Echo Chambers

The folk singer Nick Drake wrote a lyric that I’ve always been fond of: “If songs were lines in a conversation, the situation would be fine.”

What he’s trying to say is, there’s so much you can convey in a personal body of work, more so than in simple dialogue. And although he’s specifically talking about music, I think the line can apply to books just as well. A book can convey pretty much everything: emotional states, detailed environments, clashes and actions, profound inner thoughts … any good book can run the gamut of whatever a scene entails. By contrast, a good movie might only be able to utilize a few tricks, just to make a scene impactful, and a good song might only be able to make you feel emotional.

For example, my favorite song (at the moment, at least) is “Milk” by Sweet Trip, because it seems to encapsulate my life as an insomniac. In the right mood, “Milk” can make me cry, or smile, or even feel energized and inspired. But it can’t ground me into a state of profound catharsis as novels like The Idiot can. If anything, the catharsis of a favorite song is fleeting, leaving me to chase it every once in a while, for similarly fleeting moments. Meanwhile, the catharsis of a good book might leave me feeling fundamentally changed as a person.

Off the top of my head, I can name so many books that helped me grow (even if some of their authors are, retrospectively, a bit suspect): Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild helped me grow a spine and form my own opinions; Sherman Alexie’s Blasphemy taught me to validate my own anger; Patti Smith’s Just Kids affirmed my passion for an artistic life; Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch allowed me to quietly grieve in private; and Madeleine Ryan’s A Room Called Earth helped me celebrate, and appreciate, my inner nature. Now, I also have Elif Batuman and Selin to thank for giving me a sign that I’m not only alone in my thoughts—I’m not a complete headcase for thinking them.

But that’s the unique thing about novels: Since the conversation is between the narrator and the reader, no one conversation is the same. Depending on who you are, you could have a completely different conversation with the narrator than other readers.

Selin has a line in The Idiot where she’s so baffled by an ethernet cord that she asks her RA, “What am I supposed to do with this, hang myself?” I laughed out loud at that line, finding it hilarious. But when I saw Batuman do a live reading on YouTube, nobody in the room even uttered a chuckle when she got to that line. The humor was lost on them, because their take on the scene was different.

Similarly, I read Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower in a high school lit class, and while I can’t remember my own reaction to it, I remember everyone absolutely hated it. They thought it was too grimdark, and the characters were unlikable, perverted, and stupid. Fast forward to college, where most of my friends were ecologically-minded leftists, and Parable was treated like a holy book. If you even just mentioned it at a party, your street cred skyrocketed.

The extremity of emotions related to this book have always stood out to me as examples of that conversation between reader and narrator. One simply cannot help but project at least a modicum of themselves into a book, and the result is something that other forms of media can only barely replicate. It is only in the total privacy of a book’s conversation with its reader that one can feel such catharsis.

Continuing the “Conversation”

Now, I’d like to think I’m right in celebrating novels as uniquely relatable experiences, but perhaps you’ve just never been able to get that sort of feeling from reading. Perhaps other forms of media have done it for you. Or, perhaps, you have had those “conversations,” and you’d like to share how profound (or not) they were.

Either way, I implore you to share your thoughts in the comments. I have no worries about the future of reading, but I do enjoy hearing others’ experiences as readers, and I’d be happy to hear what you have to say.

(featured image: Penguin Press)

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com