NYCC 2015: “Pushing Boundaries Forward: Diversity and Representation in Comics” Panel

New York Comic Con’s “Pushing Boundaries Forward” panel had to compete with several other heavy-hitters within their time slot; readers may enjoy this thread of tweets I wrote about a guy behind me in line who ended up going to this panel by accident and managed to talk himself into sticking around. It’s a good thing that guy stayed, because the event featured a lot of valuable perspectives. The panelists did a fantastic job at educating newcomers about “boundary-pushing” within the comics space and the history of marginalized creators in the industry, while also touching on more nuanced critiques for the folks in the audience who have been to a lot of panels about this topic before.

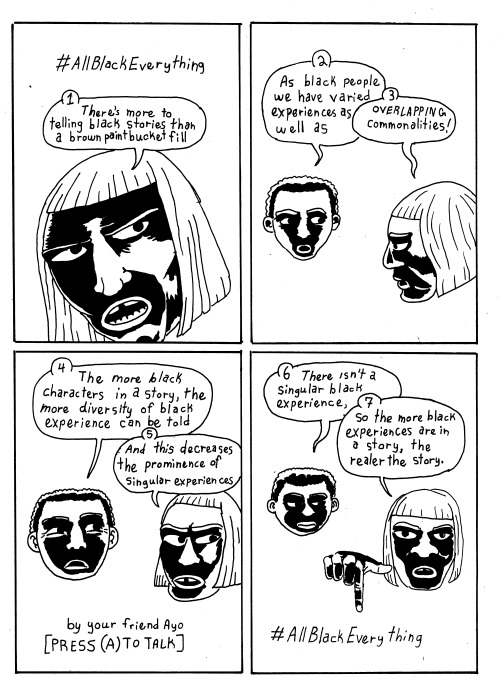

David Brothers of Comics Alliance moderated the panel, which featured Marjorie Liu, best-selling author and frequent X-Men writer, Shannon Watters of Lumberjanes, Jeremy Whitley of Princeless, Amber Garza of Geeks OUT!, Joey Stern, also of Geeks OUT!, and Darryl Ayo, who writes comics like [Press (A) To Talk] pictured above, among others.

The panel started with David Brothers introducing each panelist from right to left, allowing them to describe their work in comics and, where applicable, in activist spaces.

Shannon Watters kicked off by talking about the idea of her target audience. “A few years back when I became an editor, they asked me what I wanted to do, and I said ‘kids’ comics.’ But later that year, I was on a panel and somebody asked, ‘when you make comics, who are you making comics for?’ Everybody had really noble answers, like ‘I’m making comics for everyone!’ And I was like, ‘Uh, I’m making comics for 13-year-old girls.'” The audience laughed at this, but I think most of us here would agree that Watters’ answer is no less noble!

“Obviously my sensibility as a queer woman informs the choices that I make,” she continued. “Hiring decisions, creative decisions, the series that I choose to greenlight, et cetera. I’m really lucky to be at a company with a lot of folks who share that enthusiasm.”

Amber Garza and Joey Stern then described the origins of the organization of which they’re both a part, Geeks OUT, which Stern said “started in this room five years ago.” He had appeared on a panel about LGBTQ+ representation in comics, and the panelists decided to create an organization for those fans. “We’re buying whatever we can that has this stuff,” he said, “And no one really acknowledges it. So, Geeks OUT was getting a foothold into an already established community.”

Amber Garza joined the group later on; she explained, “They were looking for bloggers for the site, and I was interested in writing about comics, genre fiction, genre media. And I was really enthusaistic!” “And also a great writer,” Stern clarified. “That was really key.”

“There were no women on the board yet,” Garza continued. “So Joey very wisely realized, it’s probably a good idea to diversify the board. It started in this room, and then it’s been evolving – we’re very cognizant and we want to be responsible about being inclusive. When we say LGBT, we really mean LGBT. And maybe some more letters after that. But before we add them, we want that commitment to be there.”

David Brothers turned next to Marjorie Liu, asking her about her creative choices with regard to X-Men and the character X-23: “Your work was always diverse by default; that was never a question. Is that in the forefront of your mind when you’re creating stories?”

Marjorie responded, “I grew up surrounded by my Chinese relatives. I spent a huge amount of time in my grandparents’ laundry, always surrounded by cousins, always deeply immersed in Chinese culture. But I would go to school, and people would do that question that they ask when you’re mixed race: ‘What are you. What are you?’ I would say, ‘I’m Chinese-American.’ They would say, ‘No, you’re not. You’re not Chinese.’ That question – that question of otherness, that question of, what does it mean to be mixed race, and representation and inclusion, has sat with me throughout the years.

“So, when I write — yes, representation is on my mind. But also, telling diverse stories, including diverse characters in my books, bringing this into the story, feels very natural. It’s not something like, ‘ok, here’s my checklist, I must [gestures as though checking off a list].’ But yes, representation is always on my mind, because I’m aware of what it’s like not to be represented. It’s not a great feeling, when you’re growing up. Like, Jubilee was a character who I really clung to. She was Chinese-American. But there wasn’t a whole lot of that.”

Next, Jeremy Whitley described his series Princeless, which he described as “something that I was looking for before I was writing it. My daughter is a young woman of color, and I wanted to be able to share comics with her the way that I’d always loved comics. I was looking for books with characters that looked like her, that she’d be able to relate to, interesting stories that she could see herself as the hero — also, that would be appropriate for her to read …

“I couldn’t really find what I was looking for, so I started putting it together myself. It’s about Adrian, who is a young black princess — and not the Tiana kind, where she’s not actually a princess because it’s the ’20s in New Orleans. She actually gets to be in a fantasy world where she’s an actual princess and have all those great things that other princesses get to have. That’s what I wanted to do, and it kept growing out from there. She’s a character who gets locked in a tower by her parnets and decides to save herself, has her own agency, has her own adventures. It grows out into stuff like The Pirate Princess – there’s an even larger, more diverse cast there.”

Darryl Ayo described his process, which began with him simply drawing one thing per day. As he went, he began to become more aware of humanizing his characters, even the fantastical ones: “These may be characters with wings and extra arms and such, but they do correspond with real people, so I should be – be aware.”

Ayo went on to elaborate at length in respond to Brothers’ next question, which was: “What does authenticity mean when it comes to diversity? Having a picture-perfect approach to a certain culture, or something else entirely?”

Ayo said: “When it comes to authenticity — I think about this a lot, because when writing about my own experiences, I was also extremely insecure about what I was putting out. It seemed like – there was my life, in reality, and then there was the media, telling the world what black people were, what black people were about. It’s a cycle that everybody’s part of. And what happens is, you start to believe – whether explicitly or subconsciously – that there’s a certain way to be a certain person. Even though, no matter what you do, you are that person. You don’t actually escape yourself. So therefore, anything you do is an authentic experience. The thing that occurred to me, that I started saying a lot was, ‘Everything I do is a black experience.’ You see people talking a lot about what is and isn’t right to do in media. This isn’t just comics — this is politics, television, everything. I started realizing that anything I do is authentically black, and therefore, I should cut myself a whole lot of slack.”

Joey Stern piped up to discuss how this relates to media depictions of gay characters as well. “When I was a kid, and I was fat, I thought: ‘at some point I will have to lose weight if I ever want to come out.'” The audience laughed at this, but it was also clear that Stern was serious. He continued, “Sometimes people say, ‘well, it’s not authentic’ or ‘all the characters are white because that’s my life.’ But for me, especially in the world of comics … if you’re not writing your actual memoir, then you should have no problem including diversity, not only because it leads to more interesting stories down the road.”

Shannon Watters added, “If you have a gay character, their only character trait shouldn’t be that they’re gay. You can have a gay character who loves football, or loves patterned shirts, or whatever. I think about that a lot.”

Jeremy Whitley came at this problem differently due to his own privilege, which he detailed as follows: “Being a straight white guy, I get a lot of other straight white guys asking me, after panels, how to write ‘the other’. And I think a lot of people misunderstand the phrase ‘write what you know.’ What ‘write what you know’ means is, ‘don’t write things uninformed.’ Don’t just go into a story and shoot from the hip. You wouldn’t do that if you were writing about World War II. If it is more difficult for you to talk to a person of color than to research World War II, then you’re doing something wrong. The idea that you can’t talk to people and learn what it’s like to be somebody else, or run some of your work by somebody occasionally, and be like, ‘hey, is this offensive? Just checking.’ I mean, the internet is out there … Honestly, diversity is not hard, you just can’t be lazy about it.”

Marjorie Liu opened up about the idea of stereotypes and clichés. “I was just on a panel of Asian-American writers and creators where we were talking about issues of stereotypes. How do we as Asian writers address stereotypes of Asian people? Do we touch that, do we go there?”

“We were all talking about how sick to death we are of stereotypes of Asian characters,” she went on. “The over-sexualization of Asian women, kung fu gangsters, sex slaves, etc etc etc. But let’s say you’re an Asian-American writer – take me, for example, where I spent a lot of my childhood in my grandparents’ laundry. That’s a cliché, an Asian person owning a laundry. And yet, that is my authentic experience as a child growing up. How does one tackle these issues, even when you are the race that you’re writing about? I think as a person of color, we bear a burden of representation. If we write ourselves – if I write an Asian-American character – I am bearing a burden of having to write the perfect Asian-American person, because there are so few representations out there already. And so many of them malign us in some really horrible ways. So there is this pressure to create the perfect Chinese-American girl, instead of just telling a story.

“On the one hand, being authentic is being imperfect. You want to tell an authentic story with an imperfect characters. But you think, are people going to complain about this? Am I going to offend other Asian-Americans? It’s a difficult question to wrestle with. And, two, as a mixed-race person – [there is] the term ‘hierarchies of authenticity.’ As a mixed-race person, sometimes we are asked to prove our authenticity. That we are a member of the race that we say that we are. There are different ways of doing that, whether it’s through language, or culture, or whatever. I have to be ‘more Asian than Asian’ in order to prove that I am an authentic Chinese-American. These are all things that we are compelled to think about.”

Not all of the panelists agreed about the idea of stereotypes. Joey Stern said, “I prefer bad representation to no representation. Growing up gay – there are lots of terrible gay stereotypes out there the media, but I was so happy to see them.”

Liu, however, pushed back against this sentiment, saying: “I have an allergic reaction now – as a woman of color, I am allergic to bad representation. Especially written by white men. I wish that I could accept bad representations. But I cannot do it anymore. I’m done. I’ve been done for a long time.” The audience applauded loudly at this; one woman shouted “so true!” from the back.

“It’s a great thing to have the optics of diversity,” Liu continued. “It’s a great thing to look at a comic and see a bunch of Asian people. But, if they’re not represented well, then why do you bother? And secondly, if we don’t have structural diversity behind the scenes – if we don’t have writers and creators who aren’t diverse – the optics are great, but they won’t last. We can’t have great stories if we don’t have that structure in place, if we don’t have members of these diverse communities telling these stories.”

Shannon Watters also agreed that it’s time to move past accepting bad representations. “There’s so much bad stuff out there,” she said. “How many of you have seen The L Word?” The audience groaned and laughed. “There’s so much bad stuff out there! Why are we allowing more of it?!”

Amber Garza responded, “It’s all we had at the time. I remember, one of my favorite – I’m so embarrassed! I got my comics from the liquor store around the corner because they were less than a dollar and they were all in a bin. So I just got whatever I could when I was 12. There was this comic FemForce by AC Comics that had the most ridiculous gravity-defying boobs out – but I was like, ‘Look, it’s these women!’ It might say something about how I’m queer now. But it was all I had. Everything else was bulgy muscly dudes, but that wasn’t my identification. At the time, that was all I had. But it’s not acceptable, at this point in time, to have bad representation. There’s so much talent out there. There’s so many interesting stories.”

On the topic of representation marginalized characters as villains, Jeremy Whitley piped up: “It’s a question that is solved immediately by the time you get good representation. If you have plenty of good black heroes in the stories, and it’s not just this one representation, this one gangster character – he could be a great gangster character. But if he’s the only black guy in the story, then all of the black characters in your story are gangsters. If we get good representation, then you can write all kinds of characters.”

David Brothers then pointed out that Darryl Ayo had made a comic about this exact issue, which got shown on the big screen; I have included it here at the top of this post.

During the Q&A section, several questioners failed to ask a question, but the panelists still managed to share a few insights in response. When someone brought up the idea of death in comics, Darryl Ayo quipped, “I find it interesting that death is a revolving door for a lot of characters, but not for black characters.”

At one point, a woman got up to explain that she had written a comic based on her life and that all of the characters had ended up being white; she shared her feelings of guilt about this, but when asked by the panel whether she would consider changing the story’s focus, she seemed reluctant. I noticed several audience members cringing in embarrassment during this moment; the panelists exhibited remarkable patience.

Eventually, Marjorie Liu shared these thoughts: “I think it’s important to remember that people of color are not props. We’re not props. It’s not just a matter of having a checklist. You don’t need to say, ‘I need Asian person number one, I need black person number two.’ When writing outside your comfort zone, when writing a character that’s a different race – it’s important to remember and be aware of what your own privileges are. And I don’t – again, I can’t tell, just from looking, but let’s say that you are white. It’s important to be aware of what your privileges are, as a white woman. That’s step one of writing outside your comfort zone.”

Jeremy Whitley said, “Don’t confuse diversity with color blindness. Don’t just say, ‘oh, we’ll make them a different color, that’ll be fine.’ That’s misrepresenting other people.”

The panel concluded with both audience members and the panelists expressing their frustration with big-budget, mainstream comic adaptations for the screen. “1.2 billion dollars has been spent telling Peter Parker’s story on the screen,” Shannon Watters said, putting her head in her hands for a moment. “1.2 billion dollars,” she repeated.

“Even though Miles Morales is a cool dude, Peter Parker’s always going to be Spider-Man because he was first,” said David Brothers. “There’s inertia.”

The panel concluded with an audience member remarking that John Stewart was a more well-known Green Lantern than Hal Jordan; the panelists also pointed out how Samuel L. Jackson’s portrayal of Nick Fury in the Marvel movies has ultimately changed the way that character gets illustrated. So maybe mainstream comics and their attendant multimedia franchises are shaping up okay.

But it’s probably still worth checking out indies, too.

(Image via Darryl Ayo)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com