Cultures of Harassment Are Not the Norm, and They Can Be Changed, Whether Online or at San Diego Comic-Con

and let it be known

This process led [League of Legends] to a surprising insight—one that “shaped our entire approach to this problem,” says Jeffrey Lin, Riot’s lead designer of social systems, who spoke about the process at last year’s Game Developers Conference. “If we remove all toxic players from the game, do we solve the player behavior problem? We don’t.” That is, if you think most online abuse is hurled by a small group of maladapted trolls, you’re wrong. Riot found that persistently negative players were only responsible for roughly 13 percent of the game’s bad behavior. The other 87 percent was coming from players whose presence, most of the time, seemed to be generally inoffensive or even positive. These gamers were lashing out only occasionally, in isolated incidents—but their outbursts often snowballed through the community. Banning the worst trolls wouldn’t be enough to clean up League of Legends, Riot’s player behavior team realized. Nothing less than community-wide reforms could succeed. — Laura Hudson, for Wired.

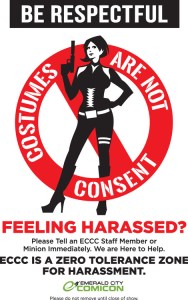

In an article for Wired magazine that only just appeared online today, Laura Hudson argues persuasively that the key to changing social networks that accept harassment as the price one pays to engage is a commitment to changing that community as a whole, not just eliminating the most identifiable bad apples. That’s one of the reasons why it’s so important for fan conventions to have clear, visible, and easily citable harassment policies. It doesn’t just allow the organizers to have a set of rules to refer to when removing violators, it also reminds folks how easy it is to not be that person. San Diego Comic-Con, the largest fan convention in the world, still lacks such a harassment policy, but you can find a petition to change that right here.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com