The Poppy War Trilogy and Other Fiction That Makes Space for Asian Women’s Violent Reaction to Colonial Patriarchal Violence

**Content warning for rape.**

Like many geeks of my generation, I devoured Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Lord of the Rings. It goes without saying that the representation of Asian women in these books was, at best, lacking, if it was there at all. Like many other minorities, I had to imagine myself in these spaces, genderflip or racebend canon characters, or simply make up my own via fanfiction.

The tide has shifted. Within the last few years, I have observed a tsunami of works of speculative fiction in English by Asian women, trans, and non-binary creators. From Julie C. Dao’s revision of Snow White’s Evil Queen in Forest of a Thousand Lanterns, to Zen Cho’s Regency comedy of manners and critique of British Empire in Sorceror to the Crown, to Fonda Lee’s wuxia-inspired saga of gangsters superpowered by magical jade in Jade City, to Yoon Ha Lee’s space opera about body-hopping, mass-murdering generals in Ninefox Gambit, to Marjorie Liu’s monster-possessed teenage protagonist in Monstress, I have never had so many riches, so many well rounded Asian or Asian-coded protagonists in stories in which they’re having the kind of adventures I once dreamed of having.

What’s remarkable to me, though, is how many of these authors aren’t merely staking their claim in genres, like fantasy, science fiction, comics, and horror, that, in the English-language world, have been historically indifferent or even hostile to their existence. They aren’t just inserting Asian characters, particularly women, in settings with spells and spaceships—although creating something fun and exciting that just happens to have mostly Asian or Asian-coded characters should be enough in a pop culture with a never-ending stream of Marvel movies and Star Wars properties that, for all their gains, are still mostly centered around white and/or cis male heroes.

What interests me most, as a longtime fan of these genres, is how these authors are using the conventions of the genre to speak back to Empire and to the patriarchy and to examine what kinds of choices their female characters must make within these systems—and, in some cases, how they fight to overturn them. In particular, I’m interested in how these women turn to incredible, often disturbing violence.

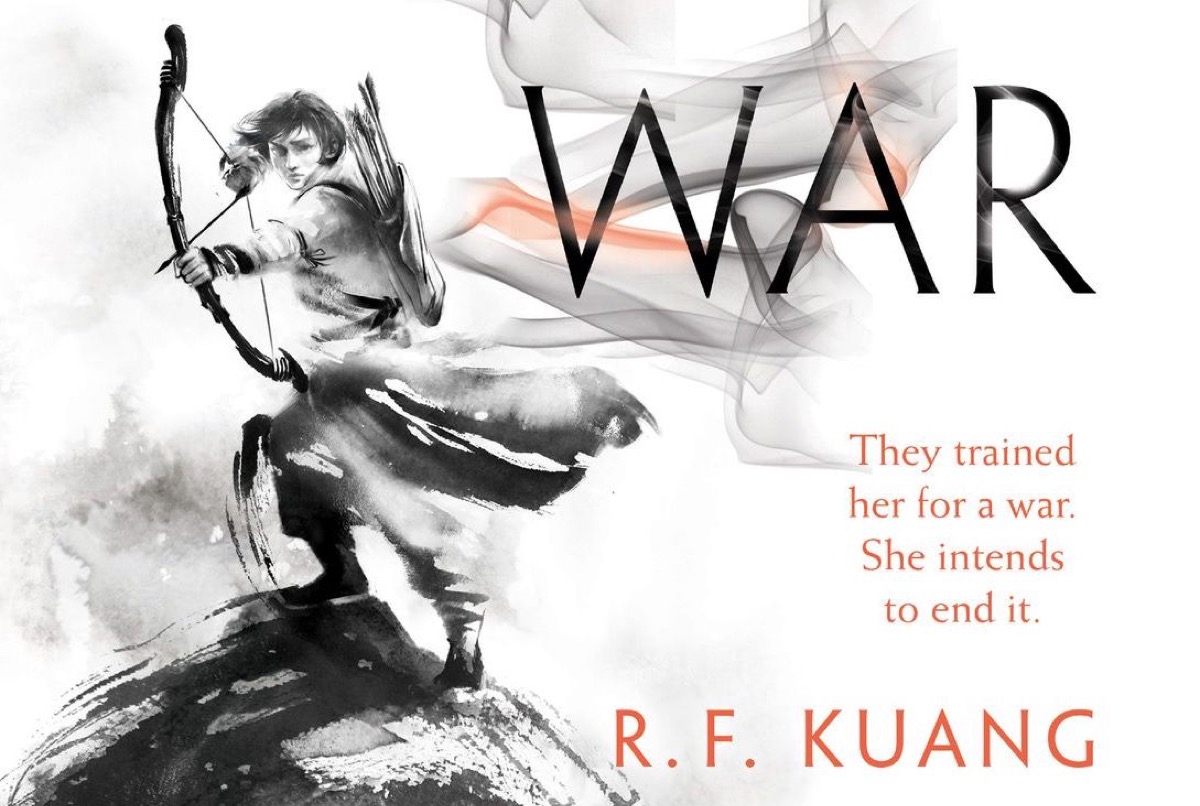

F. Kuang’s The Poppy War, a trilogy that mirrors the history of China and its relationship with Japan and the West, particularly the Second Sino-Japanese War, is a perfect example of this turn. The trilogy—whose first two novels, The Poppy War and The Dragon Republic, have been released, and whose third and final chapter The Burning God is to come in November of this year—is the story of Fang Runin, or Rin, whose life, as Kuang has stated in interviews, is inspired by Mao Zedong’s. Rin, like Mao Zedong, is not from the center of the country, called Nikan in the novels. She wasn’t born elite. What makes her interesting, though, is how her gender and poverty in particular illuminate her later choices.

Rin is an orphan adopted by a uncaring foster parents in a Southern province—a glorified, underpaid assistant in their shop. When, at sixteen, she is pressed to accept an arranged marriage with an older man, she decides, instead, to study for the Keju, the national exam, in hopes of entering the nation’s premier military academy, Sinegard.

When she, a dark-skinned Southern peasant girl, succeeds beyond anyone’s expectations, she is rudely disabused of her hopes when she goes to Sinegard and realizes she is far behind the wealthy and aristocratic, mostly Northern, students who populate the school. Bullied by teachers and students alike, she falls in with an eccentric member of the faculty and becomes dangerously fascinated with shamanic arts.

Eventually, she becomes linked to the Phoenix, one of the gods of the Pantheon, whose favor propels her rise from bullied student to feared warrior to, at the end of the second novel, leader of the Southern provinces’ uprising against the entrenched Northern elites.

On one hand, the Phoenix grants her unimaginable power over fire; on the other hand, the Phoenix’s all-consuming desire is to destroy. At times, though, it becomes painfully clear that not all of the rage Rin demonstrates is fueled by the Phoenix. It’s a rage that began with her abuse as a child, an unwanted girl, a rage that is kindled as a scholarship student at an academy of light-skinned Northern aristocrats, a rage that finally becomes an inferno when the Federation of Mugen, the counterpart to the Empire of Japan, invades and plunders the country, culminating in a horrifying ransack of a city that all too closely resembles the Rape of Nanjing.

It’s no wonder that Rin, after seeing everyone and everything she loves and cares about raped, destroyed, or murdered, commits genocide, drawing on the power of the Phoenix to trigger the volcano underneath Mugen into destroying the island nation.

What’s particularly fascinating and troubling about Rin is that her motivations are not made particularly palatable to the reader. The otherwise righteousness of her actions throughout the books is complicated and challenged.

She demonstrates a lack of empathy early on, during her time at school, when she suggests that one way to win a war of invasion is to destroy the dams protecting a river valley, drowning the invading army but also drowning the inhabitants of the valley and making their former homes uninhabitable. It’s commented upon that she lacks impulse control, reacting to most challenges, even the most minor of slights, with fire or steel. She clings stubbornly to a view of the Mugenese that is one-dimensional, as a way of keeping at bay her enormous guilt over the slaughter of noncombatants, though even then, she admits in the second book that if she were to be given the chance to make another choice, she would commit genocide again.

But what’s particularly compelling about this moment in Asian American and Asian diaspora speculative fiction is that so many of the authors are subverting these tropes, particularly the ways in which white writers have whitewashed the imperialism and invasion, freedom fighters against the Evil Empire, and ragtag bands against the elite that we see in properties like Star Wars. They’re confronting the colonialism inherent in early examples of the genre by giving these struggles back to the colonized.

Furthermore, these creators are resisting making these stories of colonialism and patriarchy tales of good vs. evil, of downtrodden colonized overthrowing mustache-twirling evil colonizers, because in real life, these stories are never simple. In the second novel, the fledgling Republic Rin fights for, in a bid to survive the civil war it’s engaged in with the corrupted Empire, brokers an alliance with their former Europe-inspired colonizers, Hesperia—an alliance that all too quickly turns sour for the Republic.

The elites in charge of the Republic, however, despite all their promises of democracy for their subjects, submit to all Hesperia’s demands. As one character puts it, the head of the new Republic will be given “so much silver he’ll choke on it.”

As for Rin, even though her rage and violence are fueled by recognizable reasons, even righteous ones, they’re still rage and violence. It’s not clear yet who Rin, who has clawed her way up through a world which has treated her primarily with scorn, exploitation, and violence, will choose to become in the final novel of the trilogy. After all, every time she wields her power on the battlefield, people burn, but too often, that’s the only trump card her side has—and oftentimes, that side doesn’t have her or the people’s best interests at heart.

That’s why I think Rin’s story and The Poppy War so aptly illustrates what’s remarkable about this moment in Asian American and diaspora speculative fiction. When you have intimate experience with the violence wreaked by patriarchy, racism, classism, and empire, why shouldn’t it bleed out in your fiction?

(featured image: Harper Voyager)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com