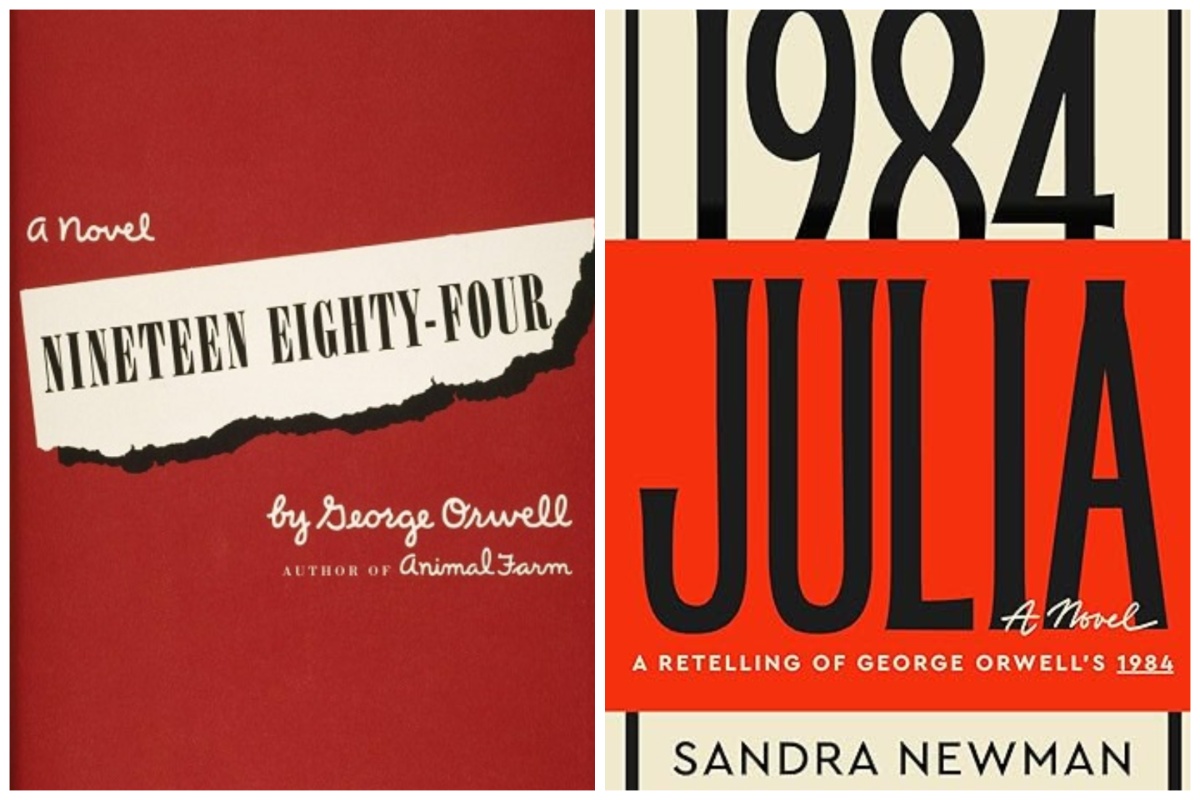

Reading ‘1984’ and ‘Julia’ Side by Side Is Compelling, Infuriating, and Depressing

Sandra Newman’s Julia (Mariner Books), a retelling of George Orwell’s 1984 from the POV of our favorite Anti-Sex League comrade, was one of 2023’s more intriguing titles. What could’ve simply been “1984, but feminist” not only illuminates both Winston and Julia, but human beings in general under fascism.

As a sucker for dystopian fiction, Orwell’s 1984 is one of my favorite novels. When I heard about Julia, I snagged a copy immediately and decided to read the two books side-by-side, alternating chapters. I’d highly recommend this to anyone who’s already a fan of 1984 and wants to enhance their experience of that book. Julia lines up perfectly with 1984 and expands the world in really interesting ways.

Julia is a “feminist 1984″

1984, told from the point of view of its male protagonist, Winston Smith, is necessarily patriarchal. Regulating people’s sex lives is one of The Party’s tools in maintaining patriotic fervor among Oceania’s citizens. If sex and marriage only exist to create new citizens, and if romantic and familial ties are not only severed but eliminated, any feelings of love and devotion can be redirected to The Party.

Winston, having been mostly raised under Big Brother’s regime with only vague memories of pre-Party life, has been conditioned to hate women. From his own mother, to his wife, Katherine, he’s learned to think the worst of women and their intentions. Therefore, his view of Julia, despite “loving” her, is a hateful one—one in which he barely cares at all about what she does if it’s not in relation to him, let alone why she does it.

When he sleeps with Julia, he’s not only giving in to his basic human drives, but he’s doing so in the most sexist way possible: Julia is much younger, thin, and attractive in a way that adheres to a mainstream, male-gazey beauty standard.

Giving Julia an inner life at all is, in and of itself, a feminist act, and Julia fills in her life’s blanks. To start, it gives her a last name—Worthing—which isn’t in the original novel. The BBC’s 1954 TV adaptation of 1984 calls her “Julia Dixon,” but Newman’s novel, having been approved by Orwell’s estate, basically makes “Worthing” canon. Julia also takes societal details that 1984 mentions in passing, like the Anti-Sex League and “artsem” (artificial insemination, The Party’s preferred method of procreation), and shows us their inner workings more fully thanks to the perspective provided by a female protagonist.

Julia also takes us beyond the events covered in 1984. By expanding what we know about the character, we learn more about Oceania and its politics. The novel sheds light not only on Oceania’s non-white citizens, but its queer citizens, too. There are characters across the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, Julia herself among them.

We learn about Women’s 21, the hostel where she lives with other young, unmarried Party women in dorms, and the very particular way that women’s lives are impacted by Party rule: from abortion, to sexual assault, to the imbalance of power between genders both in the home and at work.

So yes, Julia is a “feminist 1984,” but it being that, it also illuminates something much larger than gender.

Julia illuminates today’s world

1984 shows us Julia through Winston’s eyes, so Winston seems like the big revolutionary who’s tragically cut down by The Party, and Julia seems like a hanger-on who completes the picture Winston has for his own revolutionary life, but doesn’t herself seem particularly interested in the politics of everything.

Julia doesn’t contradict that, but it does provide the character greater context and nuance. We learn about her childhood, having been born into early Party rule. We see how she engages with the Party when Winston isn’t around, definitely playing the role of a Party faithful, but too “pragmatic” to be interested in revolution—more about getting away with things long enough to live another day.

For someone in the Anti-Sex League, she sure has a lot of sex, yet sex isn’t something Julia does to “stick it to The Man.” It’s something she does for personal pleasure, or to drown out the world. As the events of Julia get closer to Julia and Winston’s arrest, the Party uses Julia and her sexual exploits to suit their own ends.

Seeing Winston through Julia’s eyes puts his words and actions from 1984 into a new context, too. Julia’s Winston is a naïve dilettante. He talks a big game about revolution and Truth, but isn’t smart or courageous enough to pursue revolution until someone more brazen than he is comes along. Even then, he comes to the conclusion that only the proles can save them, fetishizing their political potential even as he patronizes them.

Julia shows us that neither character is as smart or revolutionary as they think they are, and both are taken in by the Party in one way or another. Winston comes to love Big Brother. Julia comes to hate Big Brother, but in finding “liberation,” ends up buying into what amounts to The Party in a different outfit.

Getting to know both characters so intimately, I wanted to shake them for their myopia. However, as I read both novels, I recognized that Winston and Julia represent most of us, which makes these books slightly depressing. We’d all like to think we’d be revolutionaries. The truth is that most people just want to get by as comfortably as possible, in as much safety as possible for ourselves and our immediate loved ones.

Most of us would be a Winston or a Julia, and no matter which we are, The Party—or a Party-like alternative—will always be in control.

The value in these books, however, is that when we become infuriated about what these characters do or don’t do in the face of their fascist regime, we can see the big picture of how their government operates around them. Hopefully this allows us to think about the big picture of our own government and how their actions affect our people as a whole, beyond our own personal interests.

(featured image: Plume-Harcourt Brace/Mariner Books)

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com