Review: Life Is Strange Episode 4 — On Soap Operas, Glurge, and Unreal Stakes

My opinion about Life Is Strange has varied widely from moment to moment, and the pacing of its most recent episode – the fourth and penultimate entry in this supernatural coming-of-age story about a time-traveling teenage girl – has left me the most flummoxed out of all the entries so far. Whenever I review a game, I try to picture who might enjoy it, even if I didn’t like it myself. That way, even if a reader disagrees with my take, they’ll be able to gauge whether or not they’ll like the game. This has proved very difficult for Life Is Strange, because the intent and the target audience for the game seem to be in constant flux.

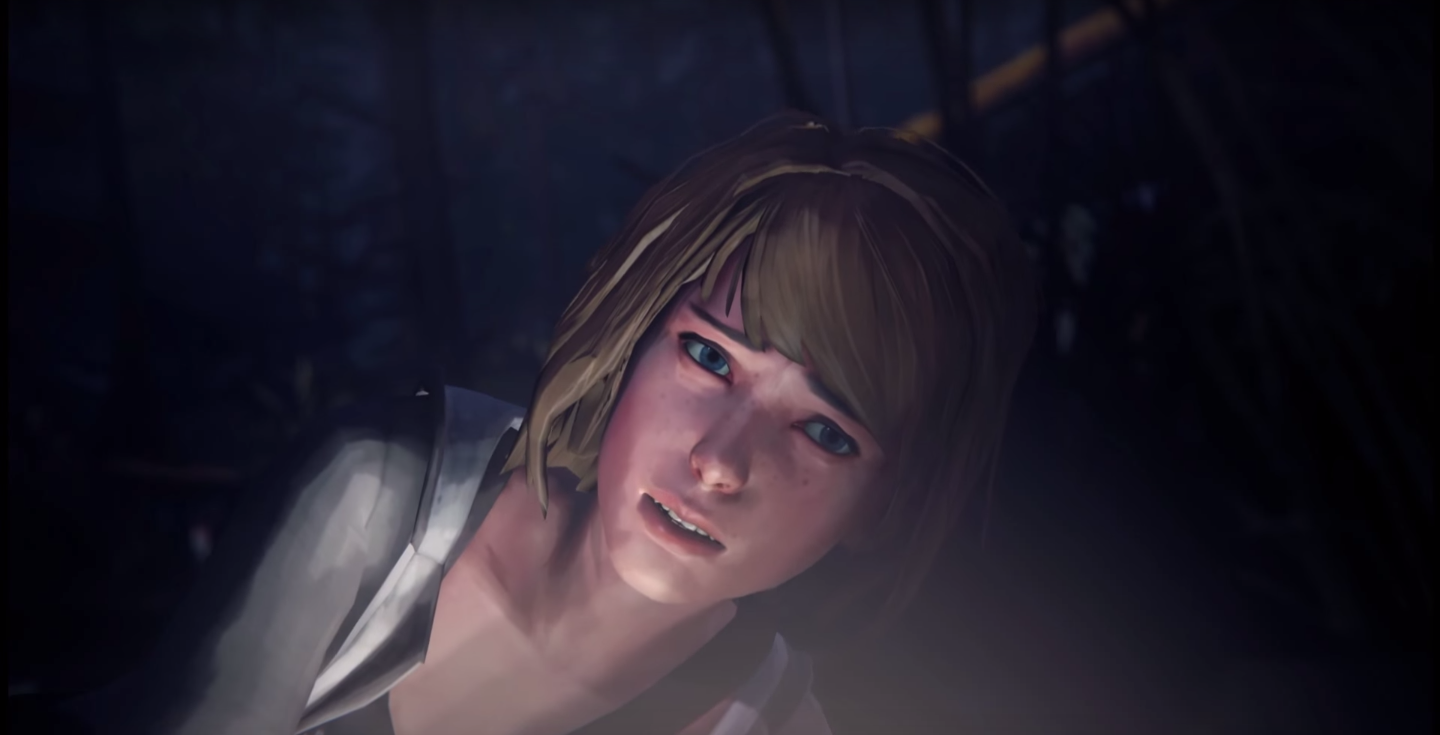

As our heroine Max Caulfield uses her newfound time-traveling powers to “help” her friends and “fix” the world around her, only to have it end in disaster at every turn, so too have I continued to justify and re-justify each of this game’s bizarre choices, only to end up with a list of you-might-not-like-this caveats. Here’s a big question that keeps nagging at me: why does this game, which finally tells a story about teenage girls in all their flawed naïvete, choose to put these girls in physical danger over and over and over?

In previous episodes, the girls in this game have had to endure sexual assault (and implied rape), horrific bullying and slut-shaming, thoughts of suicide, acting on suicide (with the option for Max to use time travel to save them, but with a chance that Max will fail), and constant brink-of-death moments. The most improbable example had to be the time when Chloe’s literally tied to train tracks as an oncoming locomotive approaches. At least Chloe’s shoelace gets stuck, so she got herself there by accident, not at the hands of a mustache-twirling villain. But the mini-game where you save her from a literal train-wreck doesn’t effect the rest of the events of the game at all. Nor do many of these other emotional manipulations – they are set-pieces, moments in which a female friend of Max (or Max herself) ends up in severe danger.

The fact that a young female protagonist does all the saving in Life Is Strange has helped assuage my discomfort at the sheer volume of damsels that Max has had to save. But the events of Episode 4 … well, there’s a lot more of the same. Strap in for a roller coaster of teen terrors, folks.

The end of Episode 3 gave us a big “gotcha” reveal in which one of Max’s time-travel attempts has huge, sweeping, unexpected effects. Without spoiling too much, but while still revealing a content warning that many readers may well want, the opening of Episode 4 involves yet another of Max’s female friends considering suicide. In this case, however, it’s assisted suicide requested by a disabled person, and the depiction is framed in much the same way as many of the other plot points in Life Is Strange: as a tearjerker moment. Not necessarily as a teachable or educational one. The extensive debates in the disabled community about assisted suicide do not come up, and regardless of the choice you make in-game, Max will always conclude that scene by traveling back in time to “fix” this person’s disability retroactively.

It’s not clear to me why this plot point got included in the game at all, especially since Max reverses it and returns to the timeline in which the entire rest of the game’s events take place. It wasn’t clear to me why Chloe ended up on a set of train tracks, either, nor did I fully understand why the game included graphic depictions of Max’s friend flinging herself from a rooftop before allowing the player to go back in time and get them some well-deserved psychiatric treatment. Why are each of these scenes framed in this way? I think I understand why: this game is an example of “glurge.”

“Glurge” is the genre of Lifetime Movies and Hallmark card poetry; it’s epitomized by films like The Bucket List or Seven Pounds or that Holiday In Your Heart movie starring a young LeeAnn Rimes. These movies have their moments, their occasional clever conversations, and maybe even a cool set-up or two – but they’re ultimately about twisting the emotional knife, over and over. Glurge gets made for folks who cried at the end of Beaches, then said, “I want that intense feeling to last the whole time.” Life Is Strange may well be the first-ever example of a glurge videogame.

I used to compare Life Is Strange to soap operas, especially teen soaps like The OC and Gossip Girl – over-the-top dramas in which unlikable-but-beautiful teens deal with all the “normal” problems of teendom, alongside much more improbable scenarios like kidnapping, meeting a literal prince and maybe-marrying him, getting sexually assaulted but then making friends with the assailant later because he’s actually pretty cool … the list goes on. The horrific unrealism of Gossip Girl is also its most charming aspect; what saves shows like that, above all, is the humanizing moments between characters like Blair and Serena. Unfortunately, this is precisely why Life Is Strange doesn’t seem to quite measure up to Gossip Girl standards, and why “glurge” seems a bit more accurate as a descriptor.

Much to-do has been made about the dialogue in Life Is Strange: is it realistic, or not? Sometimes, it is. The dialogue between these characters veers between inviting you in with show-don’t-tell prowess, then spitting you back out with an unexpectedly surreal interchange. In the game’s worst moments, it becomes glaringly obvious that a group of older white men wrote this game (which does have a multiracial cast – although the leads are slim, conventionally pretty, pale girls). The authority figures and parents in the game are by far the best-written, no doubt because they’re the ones to whom the writers could most relate. Speaking of the game’s writers, some have been oddly defensive towards critics of their game; the game developers’ timelines are filled with examples of them retweeting loads of positive tweets and reviews. It does read a little bit like an attempt to self-justify the choices that they’ve made with their game.

But, hey, that’s okay. That’s what we’d all do in their position, right? (Well, except for the “getting defensive” part – leave that out.) But their tweets lead me to believe that the writers didn’t intend to write a “glurge” game. They thought – and still think – they have written a serious, non-glurgy coming-of-age story. Which … surprises me, given the events of Episode 4, especially the various emotional “twists” therein.

If I evaluate it on “glurge” terms, Episode 4 knocks it out of the park. The entire story arc of Life Is Strange thus far has involved Max and her friend Chloe tracking down a guy who’s (at best) a would-be murderer who drugs women for fun, or (at worst) a serial rapist. By “glurge” standards, the pacing of the reveal of this guy twists the knife like good glurge should. His spooky underground bunker, featuring binders packed with photo spreads of the women he drugged and undressed (which the player will have to force Max to rifle through in order to proceed), feels terrifying to watch unfold … but that’s exactly how a good glurge tale should feel, and Episode 4 sticks the landing beautifully. When it comes to horrific, corny, nigh-impossible reveals? Episode 4 pulls out all the shock-and-awe stops.

The villain in Life Is Strange is a serial predator who keeps “binders of women” in his underground bunker.

That’ll work great for you if it’s a genre you like. But it’s undeniable that an aspect of Life Is Strange‘s glurge factor relies upon putting its lithe, innocent girl heroines in danger, over and over. The stakes get so high that it’s almost laughable; I didn’t even mind the exciting, stimulated feelings of terror that I got as the episode came to a close. But the reason why I didn’t mind those feelings is because now I know what kind of game Life Is Strange really is: it’s glurge.

I admit, I do still feel disappointed about what might have been possible for this game. Maybe I’m expecting too much, especially given the lack of diversity on the team; maybe I should be “grateful” for the soapy teenage adventures that I got, because at least there are women here, even though they act a bit like how an older-but-caring Dad might think teen girls act. I don’t look to soap opera for insightful critiques on ableism, sexism, bullying, teen suicide, assisted suicide, or any of that other stuff. Even though those elements might appear as plot points in soaps and glurgy fictions, they’re not going to be navigated in a respectful way; they’ll be used for a hit of shock value, then discarded.

Do I recommend Life Is Strange? Only if this genre appeals to you. You’ll have to do what I did, which is lower your expectations for getting a deep analysis of any of these heavy issues, assuming instead that they’ll be passed over in favor of a narrative that compounds trauma after trauma for your entertainment.

Now that I know the real genre of Life Is Strange, I’m ready for Episode 5 to conclude with something like Max’s evil twin appearing from another dimension to reveal that Chloe is a long-lost space princess who has to die in order to reset the universe. I’m not going to be taken out of the game or annoyed by the unrealism when that happens. I’ll be excited, because I’m ready to go along for this utterly goofball ride.

That said, when my clueless-but-open-minded dude friends play this game with the framing in mind that it’s supposedly an “empowering” look at growing up as a teen girl dealing with bullying and suicide ideation and disability … well, that’s the real disappointment. This game doesn’t navigate those topics with much respect at all; it passes over them for shock value at best, and uses them to provide emotional manipulation at worst. This is a thrilling tale of teen girls trying to navigate a world that hates them – which allows for a pinch of Buffy-esque feminism, but doesn’t go much further. Life Is Strange is a game that makes the suffering of these sweet pretty teen girls look beautiful, romantic and “worth it” for the twists that the player enjoys at their expense.

I can only hope the people who play this game – especially people who never were teen girls – figure out how far into the realm of fiction this depiction really is, and how exploitative its “twists” might feel to the people who aren’t able to shut their brains off for the sake of a sappy thriller. But, considering that even the game’s writers don’t seem to know what they’ve made, I’m not holding my breath that the fandom will figure it out, either.

(Video and images via Eurogamer)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com