Sexuality & Race: One DC Comics Creator’s Take On Wonder Woman

Comic Book Resources has a new feature they’re calling “The Color Barrier.” In their latest installment, they spoke with DC Comics writer/artist Phil Jimenez. We already knew he was a good person to talk to about representation in geek media, it’s why we invited him to sit on our New York Comic Con panel last year, but this time he’s speaking about Wonder Woman specifically.

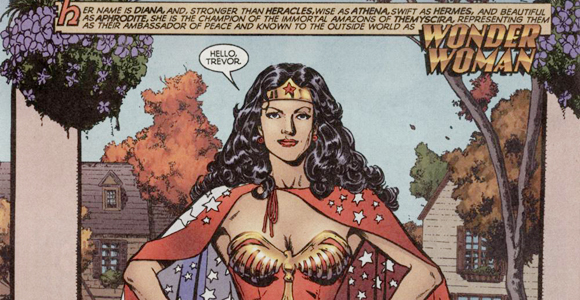

Jimenez spent two years working on DC’s Wonder Woman title (a spectacular run if I do say so myself), so he’s got a pretty good handle on the Amazon Princess. CBR asked him to speak a bit about Wonder Woman’s sexuality as he sees it:

I think sex is part and parcel of Wonder Woman’s creation. I think she and the Amazons were very much intended to explore all sorts of themes surrounding love and sex, sex and gender, and sex and power. The tragedy, of course, is that over the decades, this aspect of her character has been minimized considerably; it’s been touched upon here and there, but now the character has been refocused into a goddess of war instead of a symbol of love. Again, there are commercial and historic reasons for this (“Seduction of the Innocent,” anyone?) as well as creative ones but I agree with Mark Waid, who lamented (I’m paraphrasing) that by stripping the sex from Wonder Woman, you’ve stripped something really essential from her character, and really, the most interesting thing about her. Heck — this is my argument for the “bathing suit” costume — that costume is all about sex, sexual power, sexual defiance, body freedom and absence of shame. Of course it’s not “practical;” no superhero costume is. It’s a symbol of something else.

He also spoke about how believes the Wonder Woman of the 40s was much more progressive than the one we have now. “I’ve mentioned in other works that I believe Diana is the ultimate ‘queer’ character — meaning ‘queer’ in its broadest sense — defiantly anti-assimilationist, anti-establishment, boundary breaking,” he said, “Looking back at the early works of the 1940s, sifting through all the weird stories and strange characters, you can find a pretty progressive character with some pretty thought provoking ideas about sex, sex roles, power, men and women, feminine power, loving submission, sublimating anger, dominance in sexual roles, role playing and the like.”

Also discussed in the interview was a POC character Jimenez introduced in his run. The reaction to which he called, “mixed at best, and hostile at worst.”

Trevor Barnes, was an amalgam of two or three of my closest friends — all black men, and all comic book fans — and I wanted to create a character in the Wonder Woman universe that could represent them. And one of them is named Trevor, and I thought it was a nice play on the old “Steve Trevor” name, considering I’d planned him as a romantic interest for Diana…I’m of the belief that diverse characters have to be introduced, sometimes with quite a bit of zeal, onto consumers, who tend to be fairly conservative and attached to pretty specific iterations of their favorite characters. This is not always the case, but I find that diversity is only welcome as long as it’s introduced by the hegemony in charge; that is to say, if a straight white guy does it, it’s cool, and without agenda; if a creator of color, a female creator, or a gay creator introduces said diversity, it is often seen as full of agenda, and an obvious attempt at subversion. This is not always true, mind you, but I find it often is.

CBR also touched on Jimenez’s status as a gay, Latino creator in the comics industry.

“I certainly know I love being a representative of the gay community in our business, and I’m certainly a better gay (read: white urban gay) than Latino, in terms of visibility and representation,” he told CBR. “I’ve always seen myself as a ‘professional’ gay, someone who combines my politics and social outlook as a gay man with my work and how I choose to represent myself in my business. I claim it, find no shame in it, and I’m proud to represent, even if I’m keenly aware that I do so from a place of privilege — I have to be very careful to remember that ‘gay’ doesn’t simply mean white and male, and so if I choose to embrace this advocacy as I do, I have to advocate for all gay people, and make sure the symbols I use in my work represent the many diverse facets of the LGBT community. It’s the least I can do.”

Make sure to head over to Comic Book Resources to read Color Barrier Pt 1 and Color Barrier Pt 2 with Jimenz for tons more talk about Wonder Woman’s sexuality, gender discussions, and Jimenez’s other comic work.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com