How Sherlock‘s Finale Let Down the People Who Loved the Show the Most

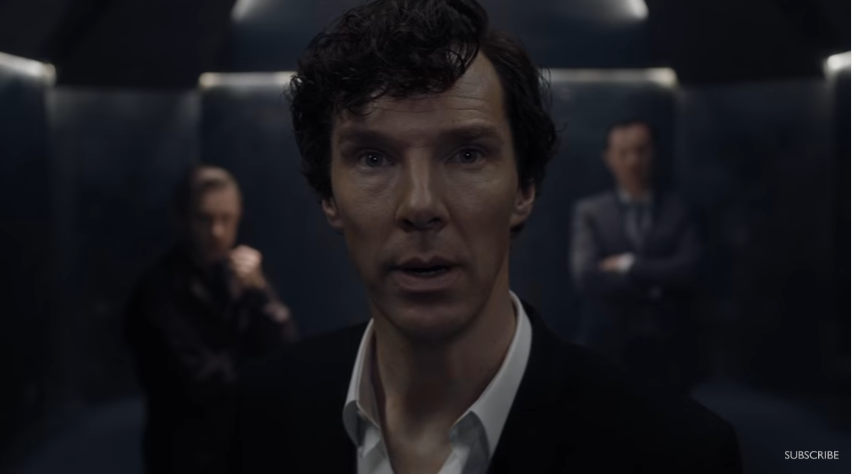

Sherlock’s success was fueled by outsiders. The modern-day reimagining of Sherlock Holmes attracted a large and adoring online fandom, composed in part by three groups—women, LGBQT people, and autistic people. Women, in addition to making up the bulk of any fan community, adored Benedict Cumberbatch/ Battenberg Cucumber/Berryman Catamaran. Queer viewers picked up on the heavy romantic subtext between Sherlock and John Watson. And autistic people embraced Sherlock as a character who gave us a rare chance to see ourselves represented—exceptional at spotting details and identifying patterns, less good at reading emotions or navigating social situations. Sherlock was a show that seemed to prize intelligence over strength, honesty over likability, and non-traditional lifestyles and relationships over a heterosexual romance arc. In short, it was a show where those who felt different for whatever reason could find a home.

Sunday’s controversial season 4 finale, “The Final Problem,” set fans off on the wrong foot before it even began, with the previous week’s cliffhanger ending. Following hints that Sherlock and his brother Mycroft—who, like Sherlock, is superhumanly intelligent and apparently uninterested in personal relationships—had another sibling, their never-before-mentioned sister Eurus, who came out of hiding and shot Watson in the head.

That particular jaw-dropping moment was dispatched fairly quickly in the next episode. She used a tranquilliser and disappeared, allowing Mycroft to explain: Eurus, like her brothers, showed phenomenal intelligence from an early age, but her emotional detachment grew increasingly ominous until she apparently killed Sherlock’s dog Redbeard and burned the house down, causing Sherlock to repress all memories of her. She is now meant to be imprisoned in Sherrinford, an island mental hospital for the world’s most dangerous criminals.

Sherrinford is one of the series’ many fan references—it was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original name for Sherlock Holmes, and has been used by other writers for a third Holmes brother. Turning Sherlock’s missing sibling into a woman was presumably writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss’ way of giving women a more prominent role in the story, but why was Eurus, the only woman, the only sibling who used the family brilliance for evil instead of good?

Compare Eurus with Mary Watson, who was killed off (in the grand tradition of ‘fridging’ female characters to give their partners something to angst about) in another one of this season’s shocking moments. Unlike Eurus, Mary was presented as warm and domestic—despite her past as a mercenary, she desired nothing more than an ordinary life of marriage and motherhood with Watson. Mary is a heroine because she prioritises emotions and family life over getting involved in dangerous crime or extraordinary feats. Eurus is a villain because she does the opposite.

Following the airing of “The Final Problem,” some disappointed fans have been tweeting ‘#Norbury’ (a code word Holmes agreed with Mrs Hudson to stop him from going too far after his actions led to Mary’s death) in protest, with many outraged that the show has, once again, coded its villains (Eurus and Moriarty) as queer while treating the possibility of a relationship between Holmes and Watson as a joke.

But if “The Final Problem” displayed the worst of Sherlock’s tendency to appropriate queerness, it similarly continued a worrying trend of appropriating autism. The writers were unwilling to explicitly characterise Sherlock as autistic or queer, but he was given superficial autistic traits, which it was suggested led to his heightened intelligence. When those same traits are applied to his sister, however, they make her an emotionless monster who can’t tell the difference between her brother laughing and screaming and, when asked if cutting herself causes pain, replies, “Which one’s pain?”

Presenting Eurus as needing to be institutionalised for her own and others’ safety echoes the worst myths about autism. For most of the twentieth century, parents of autistic children, as well as those with learning difficulties, were encouraged to place their children in often brutal institutions. “The Final Problem” reinforces the dangerous stereotype that autistic people are alien and need to be locked away from society. Making autistic traits heroic in a man but sinister in a woman also makes autistic women seem particularly unnatural. In real life, the misperception of autism as a male condition has led to many autistic women (myself included) suffering long delays in receiving a diagnosis or support.

As if to add insult to injury, Eurus isn’t even an effective villain. After taking control of Sherrinford, she traps Holmes, Watson and Mycroft in a nightmare game show, forcing them to make a series of sadistic and murderous choices in order to rescue a child from an out-of-control aeroplane. But the muddled ending revealed that the child was somehow Eurus—trapped above everyone else, unable to connect—and all her actions were motivated by a need for her brother to be close to her, including murdering his best friend, who was replaced by a dog in Sherlock’s traumatised memory.

Eurus breaks down, Sherlock comforts her, she saves Watson (who is at this point trapped in a well) and is returned to Sherrinford, now completely speechless but able to communicate with Sherlock through violin playing. Disturbingly, the character Sherlock’s sister most resembled was his love interest, Irene Adler – another seemingly formidable adversary who relied on Moriarty to outwit Sherlock before being undone by her love for the great detective. The only other women in “The Final Problem” were victims—the prison governor’s wife was bound, gagged and quickly murdered, while Molly Hooper was brought back just to confirm that she’s still hopelessly hung up on Sherlock—leaving all its female characters ultimately defined by, and at the mercy of, men.

“The Final Problem” may well be Sherlock’s last hurrah—Moffat has indicated that he wants to do a fifth series, but doesn’t know when it will happen. If this is the end, then it leaves the people who loved the show for its celebration of difference with a troubling message: that difference makes you a hero if you’re a white man, and an aberration if you’re anyone else.

Rosemary Collins is a writer and journalist based in England. Her work has appeared in The New Statesman, DIVA, The Toast and The Establishment.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com