Number Crunching Doctor Who Shows Reduced Roles for Female Characters in Moffat Era

Wibbly Wobbly Timey Wimey Stuff

For her Media Research Methods course, Rebecca Moore and several other students did a bunch of observation and data analysis right along the lines of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. Except instead of focusing broadly on television and movies, with is difficult and expensive enough, they narrowed their focus to Doctor Who, and even further to the first six seasons of the show’s modern run. Specifically, Moore, et al., were focusing on a few quantifiable attributes of the treatment of female characters, in order to confirm or deny more anecdotal claims that the show’s depiction of gender has become less progressive since the ascension of current show runner Steven Moffat.

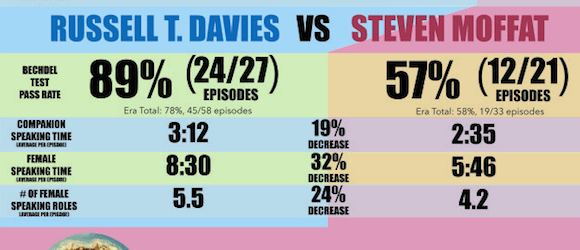

The results are pretty stark. In the transition from Russell T. Davies to Moffat, the average number of speaking roles for women in an episode has declined a quarter, and the average time in which female characters speak at all during an episode is down by nearly a third. Moore and her classmates also examined each episode to see whether it passed the Bechdel test, where the results are even more stark. Bechdel test passing episodes fall more than a third from 89% under Davies to 57% under Moffat.

The Bechdel test can be a hotly debated subject, but at its core, it lays out the absolute minimum first steps necessary to creating a film that establishes that women, in general, have any concerns and relationships in their lives other than the men in them. There must be two of them, so that a woman with voiced thoughts independent of men cannot be confused for the exception that proves the role. The characters must have names, because in the constraints of movie making, an established name means that they have reached a threshold of importance to the plot and cannot be dismissed as background players. And they must talk to each other about something other than a man or male character, to establish that they have a relationship, no matter how slight or new.

At the risk of of repeating something that has already been repeated dozens of times: the test is not intended, nor should be used, to say whether a given individual movie holds a progressive representation of women. It’s not a step by step guide for creating a movie with proper representation of women. It is for pointing out that even this very small bar, something that actual women might expect to have happen to them dozens of times in a day, is entirely absent from a massive swath of media. It is for observing a trend in filmmaking, which is also why its rules are so stringent: so that its results may be considered quantifiable data, instead of qualifiable.

(This is also something of an appropriated use of the test: it was actually, originally, described by a lesbian character in Alison Bechdel‘s Dykes to Watch Out For as the bare minimum requirements a lesbian character had for any movie she saw. In other words, the infinitesimally small seed of possibility that allowed a character to pretend, in her spare time, that, given a backstory and exposition left out of the actual film, the there might be a queer woman in the movie she’d seen.)

Moore also applied the Bechdel test to each companion of the new series individually, finding that around 75% of the time, Rose and Martha episodes passed (“Fun fact,” writes Moore, “Rose’s Bechdel test score would have been in the 80′s were it not for the episodes Moffat wrote during her run”). Donna’s one-season tenure as companion had an amazing 100% pass rate, but with Amy, the companion who immediately followed her in the transition to Moffat the pass rate plummets to 53%, barely above half her episodes.

Says Moore: “I suppose the most important thing [to avoid this statistical disparity] would be to simply write people. I think Moffat struggles with this in general, but especially when writing any sort of romantic female character.” I whole heartedly agree. I don’t think Steven Moffat himself is a deliberately misogynist monster, I just think he’s not very good at writing women or at the necessary work of altering your own perspective that comes along with writing true characters, and not pieces on the playing board of your imagination. And I do wish that a show with as much to say with its characters as Doctor Who had somebody in charge of it who was better at them. His white hot, knee gripping conclusions and mysteries are a frequent delight, but he’s shown time and time again a certain disregard for investigating the consequences of those mysteries on his characters as if they were actual people.

For the full graphic produced by Moore and her partners (which includes discussion of River Song), and the full results of her study, you can visit her site here.

(via Twitter.)

- Previous DW Stars and Creator Talk a Female Doctor

- Moffat Against Female Doctor

- Moffat Nervous About Fan Reaction to Anniversary

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com